If DNA could make music, what song would it sing? If you are Oregon State University Honors College alum Lili Adams, your guess might be something along the lines of the Mario Brothers theme song — that is, of course, if the DNA you’re listening to comes from the North American Lionepha beetle.

Born in China and raised in Portland, Oregon, Lili graduated from Oregon State with her Honors Bachelor of Science in biochemistry and molecular biology in 2020, and, today, she works as a research technician for Genentech, a South San Francisco-based biotechnology company historically regarded as the first in its field. Two years post-graduation, her work is now primarily focused on cancer immunology — a topic she finds both fascinating and incredibly rewarding — but, as Lili recounts, her first foray into the world of original research began at OSU’s Honors College, where her ear for music and aptitude for science combined to form what would eventually evolve into a truly unique honors thesis.

“It took on a life of its own.”

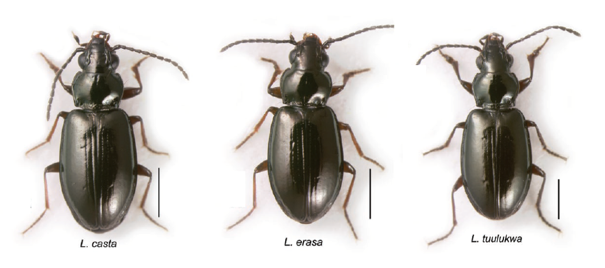

Her thesis, titled, “Sonification of DNA Chromatogram Data of Lionepha Species,” transformed scientific data into musical notes through the sonification of DNA extracted from three species of the Lionepha beetle: L. casta, L. erasa and L. tuulukwa. “When I first started it, I didn’t know where it would go. I wanted to combine art and science,” she says. “They both have patterns and can reinforce each other in some capacity.”

Having grown up dabbling in different musical mediums, from piano to the saxophone to guitar, Lili — a student employee in the lab of OSU professor Dr. David Maddison at the time — knew from the start that her research would be a marriage of her longtime passion for music and her desired fields of study, biochemistry and molecular biology. Where to begin or what that research would look like, on the other hand, was not immediately clear, prompting Lili to do something she now encourages new and incoming students to practice when they find themselves butting up against uncertainty: She turned to her support network of friends, family and peers for advice.

“If you’re struggling with your honors thesis, or any moment where you feel a bit stuck, reach out to anyone you can.”

In the end, it was her roommate who provided her with exactly what she needed to kickstart the entire project — an introduction to Dr. Dana Reason, an assistant professor of contemporary music in OSU’s School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts. A composer, pianist and musicologist, Dr. Reason not only possessed the technical knowledge and experience in the arts Lili was seeking, her existing professional relationship with Dr. David Maddison served as the bridge between art and science that would become the bedrock of Lili’s thesis.

Dr. Reason agreed to become Lili’s thesis mentor, and Lili, Dr. Reason and Dr. Maddison began meeting regularly to brainstorm ways to bring the vision for the project to life. “Dr. Reason kept pitching ideas and kept encouraging me to do more. We looked at the sources of data we had and initially came up with the idea to take photos of beetles and convert those pixels into numbers, which would then be translated into music or sound,” she says. The idea ultimately evolved from photos to DNA, which Lili would go on to analyze and convert to music using GarageBand, a digital music studio developed for macOS.

Using DNA collected from three Lionepha beetle species, Lili divided amino acids into four categories: polar, non-polar, basic and acidic, and assigned a major key to each category following music theory concepts. Polar amino acids were assigned a higher range of notes, non-polar amino acids were designated as mid-tone notes and lower range notes were assigned to basic and acidic.

The result, according to Lili, produced something akin to the soundtrack of a video game: “Very rhythmic, on beat.”

“Its use is very multi-disciplinary.”

Though pleased with the outcome, the process of completing the project was not without its challenges, Lili shares. Aside from being unfamiliar with the coding programs one would usually use to transform data into sound, at times she found herself questioning the validity of her chosen topic altogether. What was the value in taking already useful data sets and translating them for auditory consumption?

It turns out, Lili came to find, that there are multiple uses for the sounds produced from information like that collected from the Lionepha beetle. “You can just appreciate the music itself,” she says, “but you can also sense different patterns that are amplified auditorily vs. visually. It highlights certain patterns better than visual communication.”

In hospital settings, for example, complete silence is often hard to come by. In its place you are more likely to find rooms packed with machines all monitoring information from heart rate and blood pressure to oxygen and fluids, each sending various sounds into the air to alert healthcare workers of any dips or rises that occur. These sounds — whether slow and steady or quick and high-pitched — enable the dissemination of more information across multiple senses, allowing staff to divert their visual sense to one task while monitoring multiple others through their sense of sound. “They can multitask more efficiently this way,” says Lili. “Its use is very multi-disciplinary.”

This realization prompted Lili to apply to the Fulbright US Student Program, which partners with more than 140 countries worldwide to provide graduating college seniors, graduate students and young professionals with the opportunity to study, conduct research or teach English abroad. Her proposal included a plan to pursue a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering at the University of Sydney in Australia, where her goal would be to focus her research efforts on the implementation of sonification techniques to more accurately diagnose patients with mild traumatic brain injuries. Lili was announced as a semi-finalist for the program in the spring of 2022.

“It’s ok that it’s not perfect.”

Completing her honors thesis was a rewarding experience, says Lili, but it was a process of trial and error — one that brought on moments of self-doubt and frustration. When notes weren’t working out or when late nights in the student study lounge yielded little progress, she would return to her support network, often leaning on her mentor, Dr. Reason, most. “She had a lot of confidence in me and constantly encouraged me. It really pushed me to keep going,” she says. And it is that sense of community that left the most marked impression on Lili during her time as an OSU undergrad and, specifically, throughout her first venture into original research: “The Honors College really encourages and fosters critical thinking, pushing yourself and reaching your fullest potential,” she says. “It was forming those communities in those classes and meeting new people that made the difference.”

By: Adriana Fischer, Media and Communications Representative

CATEGORIES: All Stories Alumni and Friends Features Homefeature Homestories Uncategorized