David P. Turner / Januanry 5, 2024

When psychologists refer to individuals as having agency, they mean having the potential to control their own thoughts and behavior, as well as shape their environment. As humans mature, they gain independence and agency.

The term is also used by sociologists in reference to collectives of humans who are organized to fulfill a specific purpose, e.g. a nongovernmental organization such as the Nature Conservancy that aims to conserve biodiversity.

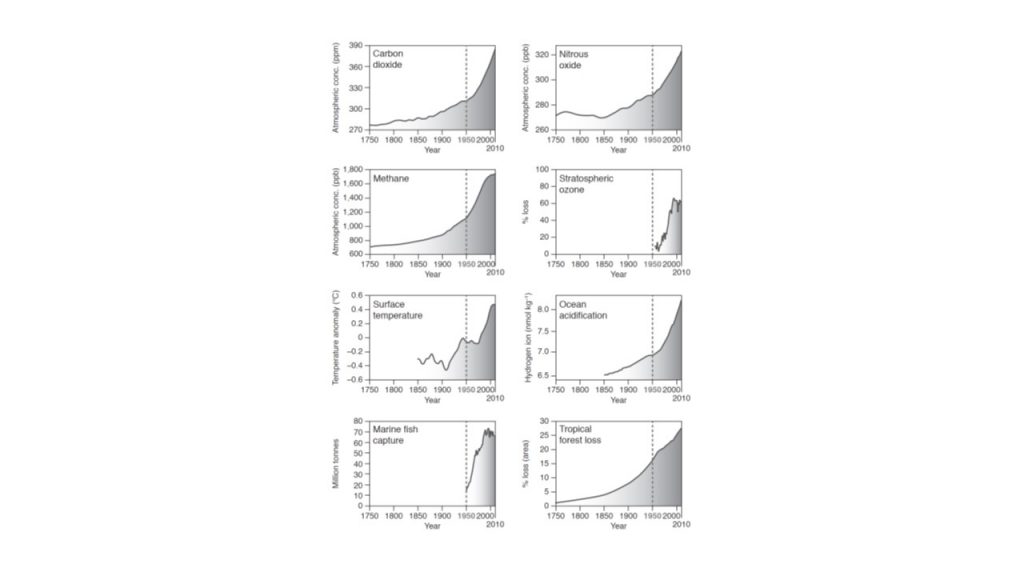

As summed effects of the human enterprise on Earth begins to significantly impact the global biogeochemical cycles, one could say that humanity as a whole is beginning to acquire agency with respect to the Earth system. We inadvertently pushed up the atmospheric concentration of CFCs to a level that significantly depleted stratospheric ozone, and we are now reducing global CFC emissions to restore stratospheric ozone. Thus far, this new form of collective agency is better able to instigate global scale environmental changes than to mitigate or reverse them in the interest of self-preservation.

Of course, human animals alone are ineffectual relative to the Earth system; it is really humans in combination with their physical machines, structures, and support infrastructure that have agency and are impacting the global environment. Earth system scientists have proposed the term technosphere for the amalgamation of humans and their manufactured artifacts. Efforts are ongoing to estimate the mass and flows of energy and materials of the technosphere, and the principles by which it operates.

The technosphere was constructed over time to support human welfare, but in some views it has taken on a life of its own, e.g. witness our great difficulty in reducing fossil fuel emissions to mitigate climate change. The rapid infusion of Artificial Intelligence into the technosphere will likely strengthen its autonomous tendency.

The view of the technosphere as autonomous, as having more agency than the humans who are part of it, has generated considerable pushback from social scientists. Firstly, it allows humans to abdicate their responsibility for technosphere impacts on the global environment, i.e. if technosphere dynamics favor ever increasing combustion of fossil fuel, what chance is there for mere humans to reverse that trend? In contrast, a social scientist might argue that we must do the work of building institutions for global environmental governance and economic governance.

A second social sciences objection to assigning the technosphere too much agency is that it is not a homogeneous entity; there is not a species-wide “we” with its associated technosphere when discussing human agency at the global scale. A relatively small proportion of humanity accounts for a large proportion of fossil fuels burned to date. Since responsibility for fossil fuel impacts resides primarily with this proportion of humanity, support is building for differentiated responsibility with respect to mitigating and adapting to anthropogenic global environmental change.

Besides the technosphere, one other form of agency in the Earth system worth contemplating is the planet itself. Geoscientist James Lovelock and biologist Lynn Margulis developed a conceptualization of planet Earth as a quasi-homeostatic system. They named it Gaia – not to imply teleology, but to suggest its active, generative nature. Despite a gradually strengthening sun and recurrent collisions with asteroids, Gaia has managed over billions of years to maintain an environment suitable for life. Gaia operates by way of interactions among geophysical and biophysical processes, including mechanisms such as the rock weathering thermostat.

At times, Lovelock was rather strident about evoking Gaia’s agency; he referred to the “Revenge of Gaia” in one of his book titles, alluding to the way Earth will react to anthropogenic changes. Philosopher Isabelle Stengers likewise elevates the agency of Gaia to the level of “intruder” on our human-centric narrative about conquering nature. These perspectives are perhaps overly anthropomorphic, but they succeed in evoking a sense of Gaia’s power.

An emerging synthesis of the ambiguities in applying the agency concept to the contemporary Earth system is the concept of Earth as Gaia 2.0. Here, the technosphere is included along with the geosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere in a new formulation of the Earth system. Gaia 2.0 is meant to suggest that a network of feedback loops, including the technosphere, will be built so that a new form of global regulation involving both conscious acts (like a renewable energy revolution) and Gaian dynamics (like increasing sequestration of CO2 in the biosphere) is achieved.

The discourse on agency in the Earth system is rather abstract, and one might ask what work is really done by elaborating the agency concept in the context of the Earth system? How does it help humanity deal with the multiple challenges posed by anthropogenic global environmental change?

Humanities scholar Bruno Latour argues that a conceptual benefit of thinking in terms of agents lies in creating a new arena of politics ̶ the politics of life agents. This new forum is where our attempts to alter the current dangerous trajectory of the Earth system (e.g. from an icehouse state to a hothouse state) will be negotiated. Besides the technosphere, the participants in this new arena include Gaia – and all the biophysical forms (e.g. the Amazon rain forest) and geophysical forms (e.g. the Southern Ocean) within it. These nonhuman forms are agents in the Earth system, though they cannot represent themselves directly; they must be represented by individual humans, civil society, and governmental institutions.

Designating Gaian agents as participants in Earth system politics reminds us of our responsibility to represent them. In my home river basin (the Willamette River, Oregon, USA), a nongovernmental organization (Willamette Riverkeepers) is currently in conflict with the federal Bureau of Land Management because BLM is not considering effects of proposed logging on fish and wildlife species, water quality, and carbon sequestration. The Riverkeepers advocate for inclusion of all the river basin components ̶ humans as well as nonhumans ̶ as co-participants in an integrated process of river basin management.

The interactions of humans, technology, and Gaia can be organized in the form of socio-ecological systems (SES) at various scales. Levels of SES organization include watersheds, bioregions, and the planet as a whole. In an SES, all the actors having agency regarding a particular resource are assembled to negotiate co-existence – again, evoking a political arena. Feedback loops within an SES that involve humans, technology, and biophysical processes must be designed to maintain economic, social, and ecological well-being across the full array of SES constituents. Building the relevant SES institutions remains a major challenge to natural resource managers.