By Will Kennerley, Faculty Research Assistant, OSU Seabird Oceanography Lab

The Birds with Fish program, a community science initiative run by the OSU Seabird Oceanography Lab, is just completing its fifth calendar year! We’re excited to share a little update on where this program stands, what we’ve found, and where we hope to go in the coming year.

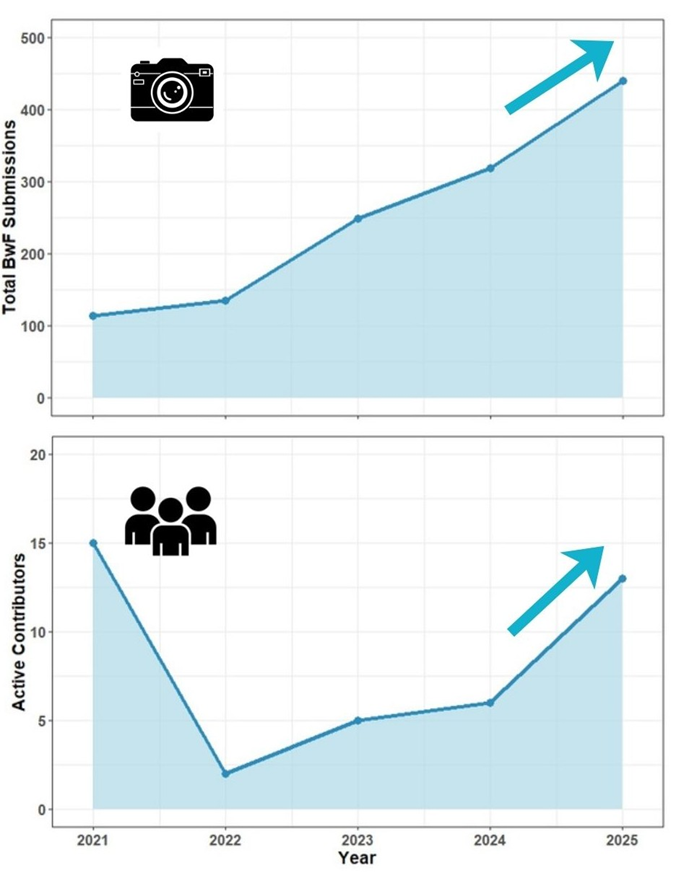

This year was a successful one for Birds with Fish, with the project receiving more than 130 new photo submissions in 2025. These new submissions represent a 35% increase in the size of our diet photo database (Figure 1) – not too bad for a single year! Of course, these submissions only come about thanks to our fantastic group of contributors. Happily, we’ve added eight new, active contributors to the Birds with Fish team during the year, increasing the size of our team. We’re hoping to increase participation further in 2026 and to reach even more nature lovers in Oregon, especially on the South Coast where we’ve so far received comparatively few submissions. Sharing a passion for Oregon’s coastal birds and habitats is a key part of the Birds with Fish program; this new year, we want to encourage you all to tell your friends about why birds and bird conservation are important to you!

Will, the Birds with Fish project coordinator at OSU, has finished identifying all 2025 photo submissions and the results are pretty incredible! Over the course of the project (440 observations), Birds with Fish has documented a remarkable 39 different coastal bird species feeding on 36 unique prey types! This diversity of both predator and prey has completely blown us away. These numbers really speak to the incredible value of Oregon’s coastal and marine ecosystems for so many different bird species.

In 2025, Pigeon Guillemots were our most commonly documented bird (Figure 2). Other popularly submitted birds include Common Murres, all three cormorants, gulls, terns, and herons. These species exploit an array of coastal habitats, from brackish estuaries to open ocean, and sandy shores to rocky coasts. These species thus provide a great way to monitor changes in prey available in a diverse set habitats all throughout the year.

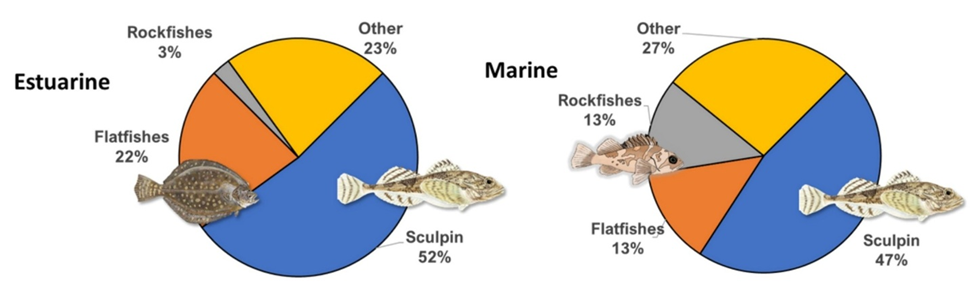

Unsurprisingly, the types of prey available to predators can vary greatly with a predator’s foraging habitat. This is something we can begin to examine ourselves in those species with lots of observations. A preliminary look at our data show that the most common prey item for Pigeon Guillemots along the Oregon Coast is sculpin (Family Cottidae), shown below in Figure 3 in blue. However, it’s interesting to note that the secondary prey of Pigeon Guillemots varies by habitat; in estuarine areas like Yaquina and Tillamook Bays, guillemots are seen feeding on flatfishes 22% of the time. However, in marine environments like Haystack Rock, guillemots also feed frequently on juvenile rockfishes (Sebastes spp.). As our data set increases in size, we’ll be able to look into habitat-prey relationships for more species, and hopefully even track how these might change over time, as well.

This is a great illustration of the value of community science – when we have more participants sampling at more locations, we’re able to capture more of the tremendous variability in seabird diets. As the years go on, it’s become increasingly clear that this is more than any professional team could do alone. With continued community support and involvement, we hope our sample sizes will continue to increase and more people will join our collaborative effort to learn more about seabirds together.

From all of us at Birds with Fish, thank you for your participation! Our project wouldn’t exist without everyone’s dedication and it’s been so much fun getting to see all of the incredible photographs that have been submitted from up and down the Oregon Coast. We’re wishing everyone a happy holidays and we’re excited to continue learning more about Oregon’s coastal birds in the New Year!