Bing Wang, CQLS; Marco Corrales Ugalde HMSC; Elena Conser HMSC

By leveraging the scalability and parallelization of high-performance computing (HPC), CQLS and CEOAS Research Computing, collaborated with PhD student Elena Conser and postdoctoral research scholar Marco Corrales Ugalde from Hatfield Marine Science Center’s (HMSC) Plankton Ecology Laboratory to complete the end-to-end processing of 128 TB of plankton image data collected during Winter and Summer of 2022 and 2023 along the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States (Figure 1a) .The workflow, which encompassed image segmentation, training library development, and custom convolutional neural network (CNN) model training, produced taxonomic classification and size data for 11.2 billion plankton and particle images. Processing was performed on the CQLS and CEOAS HPC and Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center Bridges-2, consuming over 40,000 GPU hours and 3 million CPU hours. CQLS and CEOAS Research Computing provided essential high-performance computing resources, such as NVIDIA Hopper GPUs, IBM PowerPC system, and multi-terabyte NFS storage. In addition, these computing centers contributed with software development that expedited the processing of images through our pipeline, such as custom web applications for image visualization and annotation, and automated, high-throughput pipelines for segmentation, classification, and model training.

Project introduction

Plankton (meaning “wanderer,” in Greek) are composed of a diverse community of single-celled and multicellular organisms, comprising an extensive size range from less than 0.1 micrometers to several meters. Planktonic organisms also vary extensively in their taxonomy, from bacteria and protists to the early life stages of fishes and crustaceans. The distribution and composition of this diverse “drifting” community is determined in part by the ocean’s currents and chemistry. Marine plankton form the foundation of oceanic food webs and play a vital role in sustaining key ecosystem services, such as climate regulation via the fixation of atmospheric CO2, the deposition of organic matter to the ocean’s floor, and by the production of biomass at lower levels of the food chain, which sustains global fisheries productivity. Thus, understanding plankton communities is critical for forecasting the impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems and evaluating how these changes may affect climate and global food security.

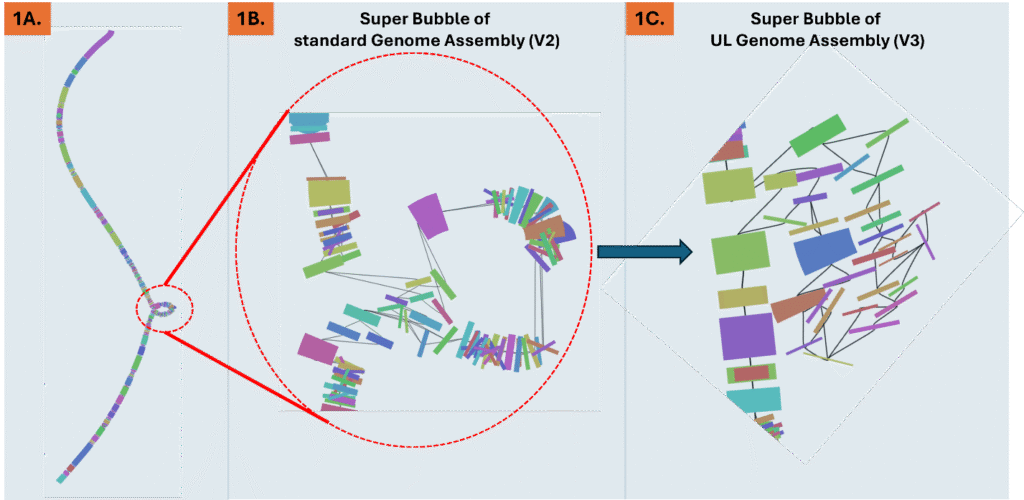

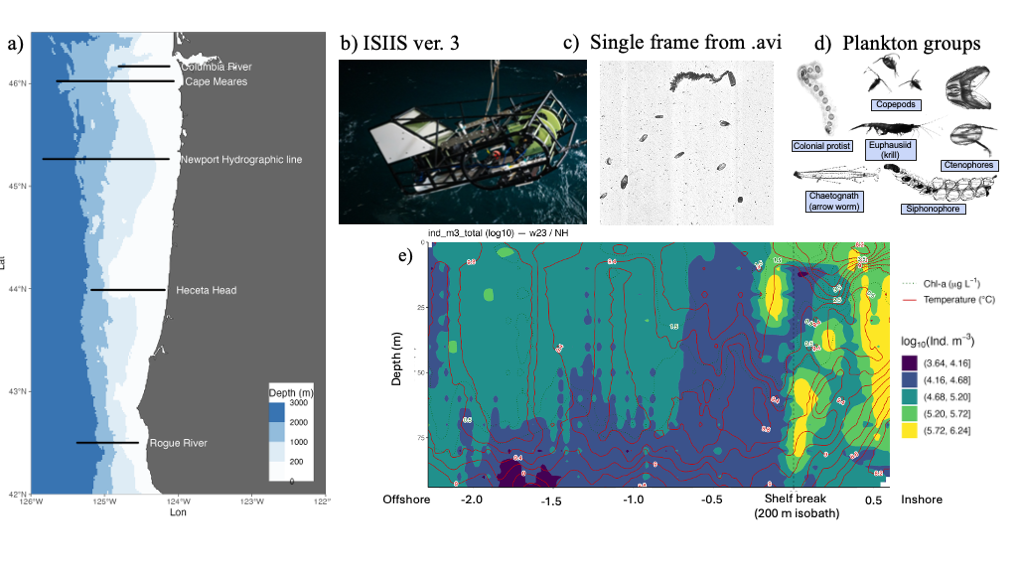

Figure 1. Plankton imagery was collected along several latitudinal transects through the Pacific Northwest coast (a), by the In-situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System (ISIIS) (b). This data is split into frames (c) and then individual plankton and particle images (d). The high image capture rate (20 frames/second) along a large spatial range allows to provide a detailed description of plankton abundance patterns (colors in panel e) and their relation to oceanographic features (Chlorophyll concentration, dotted isolines, and Temperature, red isolines).

HMCS’s Plankton Ecology Lab, in collaboration with Bellamare engineering, has been the lead developer of the In-situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System (ISIIS), a state-of-the-art underwater imaging system (Figure 1b) that captures in situ, real-time images of marine plankton (Figures 1c-d). It utilizes a high-resolution line-scanning camera and shadowgraph imaging technology, enabling imaging of up to 162 liters of water per second with a pixel resolution of 55 µm, and detecting particles ranging from 1 mm to 13 cm in size. In addition, ISIIS is outfitted with oceanographic sensors that measure depth, oxygen, salinity, temperature, and other water characteristics. ISIIS is towed behind a research vessel during field deployments. In a single day, a vessel may cover 100 miles while towing ISIIS. ISIIS collects imagery data at a rate of about 10 GB per minute with its paired camera system. A typical two-week deployment produces datasets containing more than one billion particles and approximately 160 hours of imagery, resulting in over 35 TB of raw data. This unprecedented volume of data, together with its high spatial resolution and simultaneous sampling of the environmental context (Figure 1e) allows to address questions of how mesoscale and submesoscale oceanography determine plankton distribution and food web interactions.

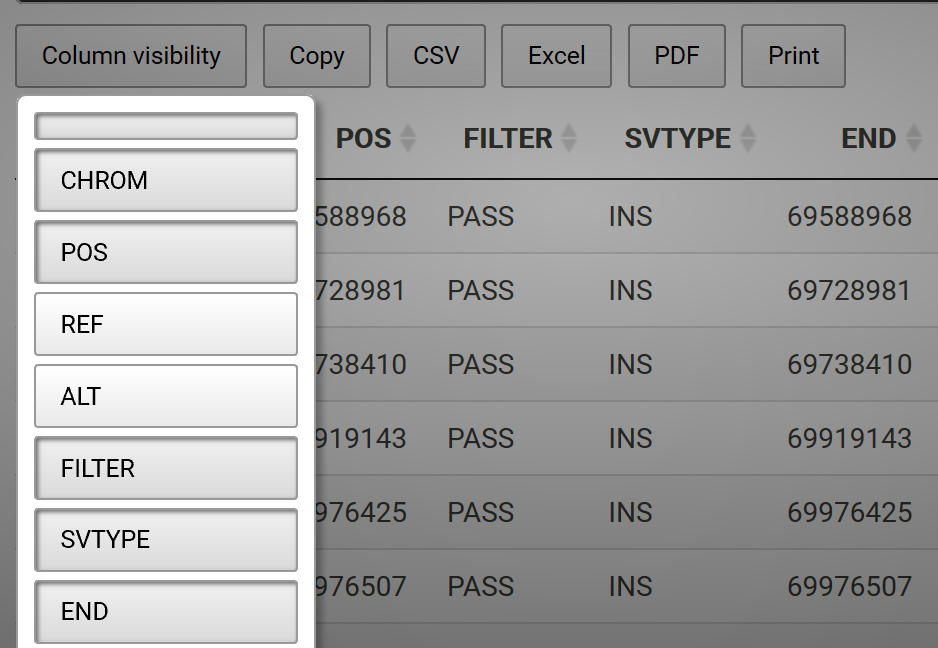

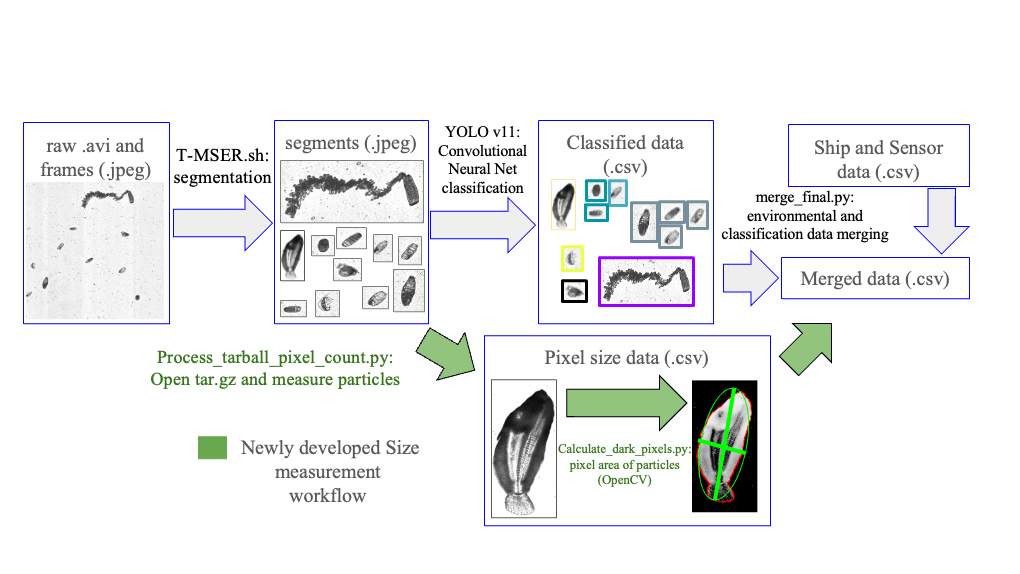

Processing this vast amount of data is complex and highly demanding on computing resources. To address this challenge, CQLS and CEOAS Research Computing developed a comprehensive workflow encompassing image segmentation, training library construction, CNN model development, and large-scale image classification and particle size calculation. In the first step, raw imagery is segmented into smaller regions containing regions of interest. These regions are subsequently classified using a CNN based model (Figure 2). In earlier work, a custom sparse CNN model was developed for classification, but thanks to significant advances in computer vision, more efficient models such as YOLO (“You Only Look Once”) have been developed. To train a new YOLO plankton model, a training library of 72,000 images across 185 classes was constructed. Additionally, a test library of 360,000 images was curated to verify model accuracy and ensure robust performance. This improved workflow was applied to 128 TB of ISIIS video data, enabling the classification and size measurement of 11.2 billion images.

Figure 2. Data processing workflow from raw video to training library development, model training, and plankton classification and particle size estimation

Hardware and software support from CQLS and CEOAS research computing

CQLS and CEOAS Research Computing provide high-performance computing resources for research and is accessible to all OSU research programs. The HPC has a capacity of 9PB for data storage, 45TB of memory, 6500 processing CPUs, and 80+ GPUs. The CQLS and CEOAS HPC can handle more than 20,000 submitted jobs per day.

1. GPU resources

Multiple generations of NVIDIA GPUs are available across architectures on the CQLS and CEOAS HPC, including Tesla V100, Grace Hopper, GTX 1080, and A100, with memory capacities ranging from 11 GB to 480 GB as listed below. GPUs are indispensable for image processing and artificial intelligence, delivering orders of magnitude faster performance than CPUs.

In this project, GPU resources were employed to train YOLO models and to perform classification and particle size estimation of billions of plankton images.

- cqls-gpu1 (5 Tesla V100 32GB GPUs), x86 platform

- cqls-gpu3 (4 Tesla T4 16GB GPUs), x86 platform

- cqls-p9-1 (2 Tesla V100 16GB GPUs), PowerPC platform

- cqls-p9-2 (4 Tesla V100 32GB GPUs), PowerPC platform

- cqls-p9-3 (4 Tesla V100 16GB GPUs), PowerPC platform

- cqls-p9-4 (4 Tesla V100 16GB GPUs), PowerPC platform

- ayaya01 (8 GeForce GTX 1080 Ti 11GB GPUs), x86 platform

- ayaya02 (8 GeForce GTX 1080 Ti 11GB GPUs), x86 platform

- coe-gh01, grace NVIDIA GH200s, 480 GB memory, ARM platform

- aerosmith A100, 80GB memory, x86 platform

2. CQLS GitLab

CQLS hosts a GitLab website to streamline project collaboration and code version control for users. https://gitlab.cqls.oregonstate.edu/users/sign_in#ldapprimary

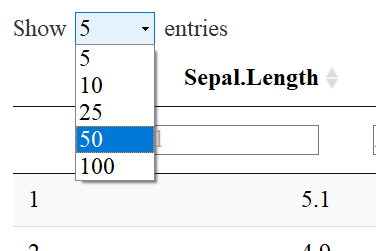

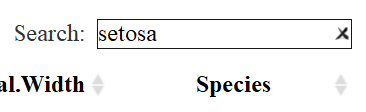

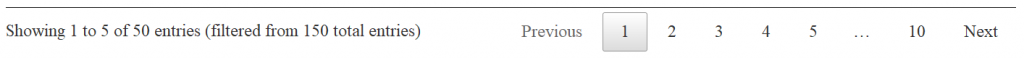

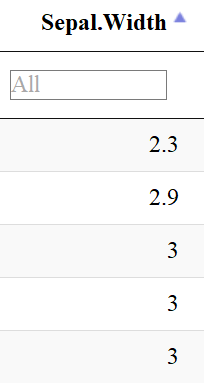

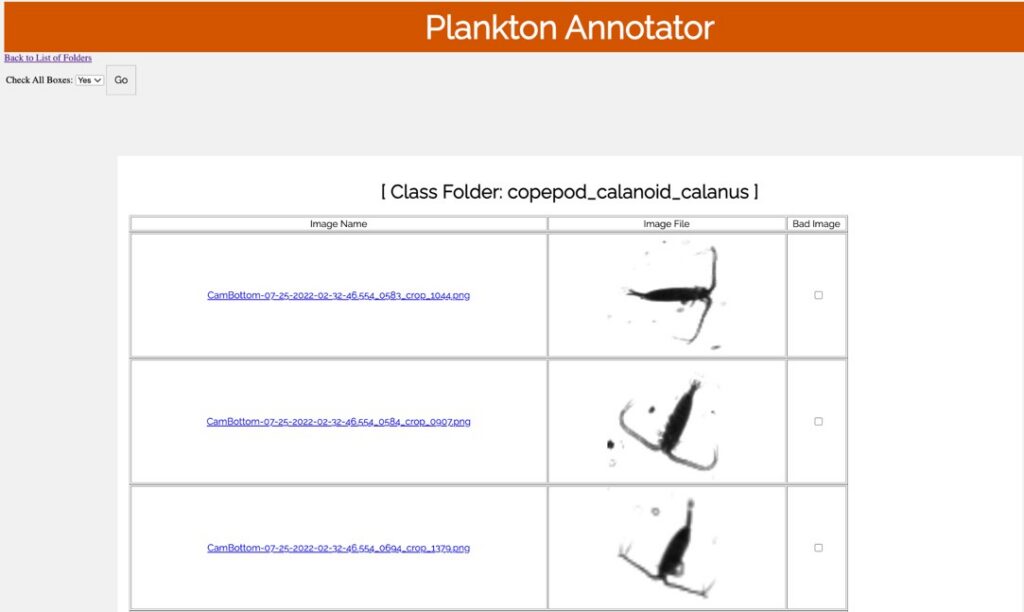

3. Plankton annotator

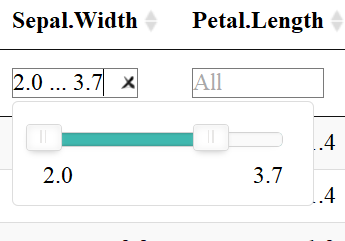

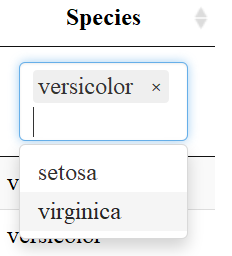

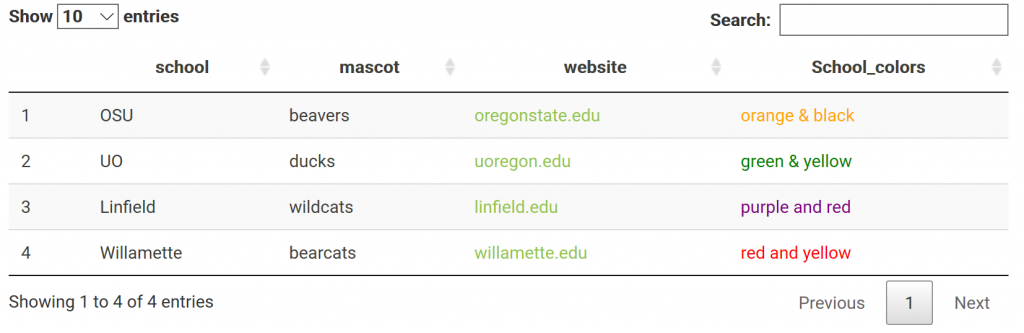

Plankton Annotator (Figure 3) is a web application developed by Christopher M. Sullivan, Director of CEOAS Research Computing. The tool provides an intuitive platform for the visualization and annotation of plankton imagery. The CQLS and CEOAS Research Computing has the capacity for developing and hosting various web applications. In this project, the Plankton annotator was used to efficiently visualize and annotate plankton images, supporting the creation of reliable training library for downstream YOLO models training.

Figure 3. Plankton annotator web application

4. Pipeline developments

CQLS and CEOAS Research Computing has a team of consultants with various programming expertise such as Shell, Python, R, JavaScript, SQL, PHP, and C++. They are available to collaborate on grant proposals, project discussions, experimental design, pipeline development, and data analysis for a wide range of projects in bioinformatics and data science. For this project a series of automated, high-throughput pipelines were updated and created to support image segmentation, model training, species classification and particle size estimation. These pipelines were designed to handle large volumes of data efficiently, ensuring scalability, and reproducibility.

5. Storage

In this project, CQLS and CEOAS HPC provided more than 200 TB of centralized NFS storage to accommodate both raw and processed data. This shared storage infrastructure ensures reliable data access, supports efficient file sharing across the HPC environment, and enables seamless collaboration among researchers.

References

Conser, E. & Corrales Ugalde, M., 2025. The use of high-performance computing in the processing and management of large plankton imaging datasets. [Seminar presentation] Plankton Ecology Laboratory, Hatfield Marine Science Center, Oregon State University, Newport, OR, 19 February.

Schmid, M.S., Daprano, D., Jacobson, K.M., Sullivan, C., Briseño-Avena, C., Luo, J.Y. & Cowen, R.K., 2021. A convolutional neural network based high-throughput image classification pipeline: code and documentation to process plankton underwater imagery using local HPC infrastructure and NSF’s XSEDE. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Belmont Forum, Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, vol. 10.

Oregon State University, 2025. Oregon State University Research HPC Documentation. Viewed 18 September 2025, https://docs.hpc.oregonstate.edu.

Ultralytics Inc., 2025. Ultralytics YOLO Docs. Viewed 18 September 2025, https://docs.ultralytics.com.