By Kirsten Steinke, Ph.D. student in Ocean Ecology and Biogeochemistry

I wake up and rub my eyes as my 5:45 alarm goes off in the morning. Still pitch black out my window, I quickly throw on my workout clothes, grab my yoga mat and head to the lounge for 6 am group yoga. After spending thirty minutes waking up my muscles, I head to the gym for my morning workout routine with my buddy Ken: a three-mile run on the treadmill while watching an episode of Rick and Morty. Sufficiently sweaty, I head to the girl’s bathroom (which is way nicer than the one I have at home) and take a quick shower. Finally awake, I head back to my room and get my stuff together for the long day of work. I look out my window again and the sun is just starting to rise behind the glacier. I stop what I’m doing and take a minute to just watch. I can hardly believe that this is the view I get to start my day with every morning.

After the winter solstice on June 22, the sun started returning rapidly to our region of the Western Antarctic Peninsula (wAP). The sunrise is a welcome site as in the dead of winter we were only getting about 3-4 hours of sunlight every day. In total, our OSU research team spent about six months conducting research and living at one of the Antarctic research stations owned by the United States Antarctic Program (USAP): Palmer Station. Palmer is situated on Anvers Island in the northern part of the Western Antarctic Peninsula. The smallest of the three research stations run by USAP, Palmer looks out over the Southern Ocean and the vast mountain ranges that are typical of the Antarctic Peninsula. The setting is spectacular: We watch icebergs float in and out of the surrounding bays and listen to the earth-shattering eruptions of the glacier calving nearby. One iceberg, dubbed Old Faithful, got stuck in the bay and stays with us all season. It is comforting in a way to see it standing faithfully by each day as we begin our field work.

“Why on Earth are you going to Antarctica in the middle of winter?” was a common question that I, and the rest of my research team, got asked. Believe it or not, the changes that occur in Antarctic ecosystems during the winter are poorly understood. Our team of krill researchers sought to fill some of these knowledge gaps as we conducted experiments on the overwintering of arguably the most important keystone species in Antarctic ecosystems: Antarctic krill. These tiny crustaceans, about as big as the length of your pinky as adults, support most of the top predators in the Antarctic ecosystem. Whales, penguins, seals, fish and other seabirds rely on krill as their primary food source.

Our research project was designed by my advisor, Dr. Kim Bernard. She’s interested in how the warming at the northern wAP affects the food available to krill throughout the autumn and winter. The northern wAP is warming quicker than most other places on Earth, which has altered the food web dynamics at the northern WAP. Krill feed primarily on diatoms (microscopic algae) and copepods (microscopic zooplankton). The warming temperatures have resulted in declines in diatoms but more copepods at the northern wAP. Winter is a critical life history stage for young krill as food availability decreases in response to lower light levels. We wanted to know how this climate-induced change in food availability, compounded by the overall lower levels of food availability, affects the physiology of young krill. Hence, six months of Antarctic research collecting, observing, and learning from our kriller friends.

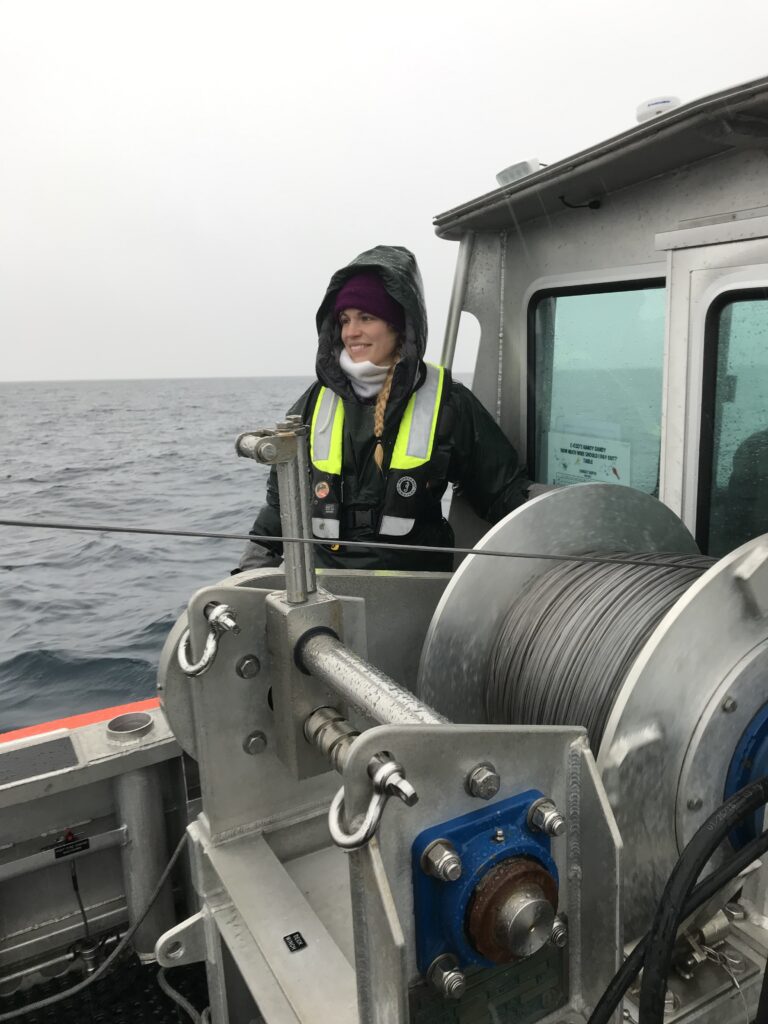

While these six months may have been the most demanding of my Ph.D. career, they were also some of the best months of my life. We worked long hours in the lab and out in the field six days a week, making sure we had enough resources to support our long-term feeding experiment and to carry out our physiological experiments. Similar to the krill, we learned how to adapt to the extreme winter conditions. We got used to working in complete darkness, learned which path to take to work when winds were blowing over 100 knots and discovered that the quickest way to warm our fingers and toes after a long day of field work was to hold them directly against the small space heater in our office.

Our long field season at Palmer Station, Antarctica finally came to an end in the middle of October. In addition to the hundreds of samples that we successfully obtained from our research project, we left Palmer with new memories, incredible stories and 17 new friends that we were lucky enough to call our polar family. This experience was truly one of the greatest of my life and I cannot wait until our next field season starts in February 2021. It’s going to be kriller.

Webpage: https://steinkki.wixsite.com/kirstensteinke

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Kirsten_Steinke