David P. Turner / August 20, 2024

Wood is an iconic renewable resource ̶ trees grow, wood is harvested, new trees are planted, and more wood is produced. On a managed forested landscape growing trees with a 100-year time to maturity, a forester can maintain a sustained yield of wood by harvesting and replanting patches totaling 1% of the total area each year.

However, not all commercially processed wood comes from sustained yield forests. Cutting of previously unlogged natural forests (i.e. primary forests) in the boreal and tropical zones is still widespread. Removal of the large trees in tropical forests is often followed by land use change.

Natural forests (currently about one quarter of the total forested area globally) are valued for multiple ecosystem services ̶ notably conservation of biodiversity, provision of fresh water, and carbon sequestration. They also provide a home to forest-dwelling indigenous people around the world. Thus, reducing the loss of tropical natural forests to logging is a high conservation priority.

Like many natural resources, wood supply is heavily influenced by economic globalization. Under neoliberal free trade economics, wood enters the global market based primarily on the cost of production. If manufacturers can obtain logs relatively cheaply from first entry of natural forests rather than from sustainably managed forests, they are economically compelled to do it. Pushback against this ideology is coming from regulators, NGOs, and advocates for indigenous people’s rights.

Global Wood Demand

To determine if the total global demand for wood could be sourced from sustainably managed forests, let’s first examine the magnitude, geographic pattern, and trend in wood demand.

Wood is commercially processed in the form of roundwood, with predominant uses of commercial wood as construction materials, paper/packaging, and biomass energy. The projected long-term trend is for continued annual increases (1-3%) in global roundwood demand.

Current global roundwood consumption is on the order of 4 billion cubic meters per year. The highest wood consuming country is the U.S. Second is China, however, much of China’s consumption is imported, moves through a value-added product chain, and is exported. China is the largest importer of unprocessed logs and the largest global producer of plywood and paper. Other historically large consumers of roundwood include several countries in the EU. New sources of demand are emerging in developing countries.

Use of wood in buildings will increase in coming decades driven by expansion of the housing sector (more people and higher standards of living). Wood will be a preferred component in new construction because of both advances in materials science, and the carbon benefits of substituting wood for steel and concrete.

Demand for paper and cardboard is rising 3-4% per year, in association with its soaring use in packaging.

Wood demand for combustion in biomass energy power plants is also on the rise (~5%/yr) mostly because emissions from biomass energy power plants are considered carbon neutral in some domains (e.g. the E.U.).

Global Wood Supply

Roundwood comes into the global production stream from a great variety of sources. Besides unsustainable cutting in natural forests, we might identify a continuum of sustainable forestry management approaches along an axis based on the importance of wood production relative to other ecosystem services. The continuum extends from plantation forestry, through modified natural forests, to undisturbed old-growth forests.

Supply from Sustainably Managed Forests

Boreal Zone

In Scandinavian countries, a large proportion of wood removals is from previously harvested and replanted boreal forests. However, the total volume produced is relatively small.

Temperate Zone

After hundreds to thousands of years of human occupation, the temperate zone has relatively little natural forest remaining. In the temperate zone, softwood species (conifers) are generally managed by clear-cutting and replanting, whereas hardwood species are usually harvested by selective cutting. Managed forests in the temperate zone are primarily in European and North American countries. New Zealand, Australia, Chile, and China have also developed extensive areas of planted forests.

Tropical Zone

Sustainable management of tropical forests based on selective cutting with suitably long re-entry times is possible, but not yet widespread. Plantation forests in the tropical zone grow relatively fast and thus have a short rotation time (and faster return on investment). The area of planted forests in the tropics is increasing.

Supply from Natural Forests

Most of the wood production in Russia and Canada is from natural forests. In Russia, much of this logging is essentially a “mining operation”, with corresponding negative impacts on biodiversity.

Logging of tropical hardwoods in natural forests is extensive in most regions where tropical moist forests grow. After tree removals, the land is commonly used for grazing, commercial agriculture, or subsistence agriculture. In Indonesia, deforestation is often associated with conversion to palm oil plantations. In Central Africa and parts of the Amazon Basin, high value trees are removed for export and the land is left as secondary forest.

Much of the wood from cutting in tropical natural forests is exported to manufacturing centers like China (about two thirds) and the EU.

Because of the rapidly increasing area of plantation forests, the proportional contribution of natural forests to the global wood supply is declining. However, completely shutting down that wood source for conservation purposes would significantly diminish global wood production. A first order analysis by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) suggests that the current global wood demand could largely be met by sustainable forestry (i.e. without cutting in primary forests) if about half of the world’s forests were used in wood production (the rest being devoted to provision of other ecosystem services. Projected increases in wood demand could not be met with the land base available for wood production. WWF proposes a reduction in per capita wood consumption, but a more likely outcome would seem to be increased per unit area productivity associated with more intensive forest management.

The Role of Forest Certification

Consumers of forest products increasingly insist on evidence that the associated wood was harvested sustainably. Consequently, there is an growing interest in sustainable sourcing within the forest products industry.

A key to ending the supply of wood from first entry into natural forests is forest certification. Buyers and sellers of wood can use certification as proof that their business practices are not contributing to deforestation or forest degradation.

Certification authorities are usually nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations. Forest management on a particular piece of land is certified based on management practices, including harvesting and replanting. Certification is also applied to wood itself in various stages of the supply chain.

Major retailers like Home Depot and IKEA have made concerted efforts to provide certified wood. Approximately 13% of the global forestland is certified, and the trend is upward.

A significant cost premium must be absorbed by forest managers, manufacturers, retailers, and consumers when managed land or wood products are certified. The willingness to pay that premium depends on educating wood consumers about issues with forestry practices. At the national level, policies supporting restriction of uncertified wood imports are becoming more common.

Chinese manufactured wood exports are sometimes routed through Vietnam and Malaysia to subvert attempts by companies in the EU and US to accept only certified wood products. A promising technology for enforcement of certification labeling involves tracing the origin of logs or wood by use of genetic information.

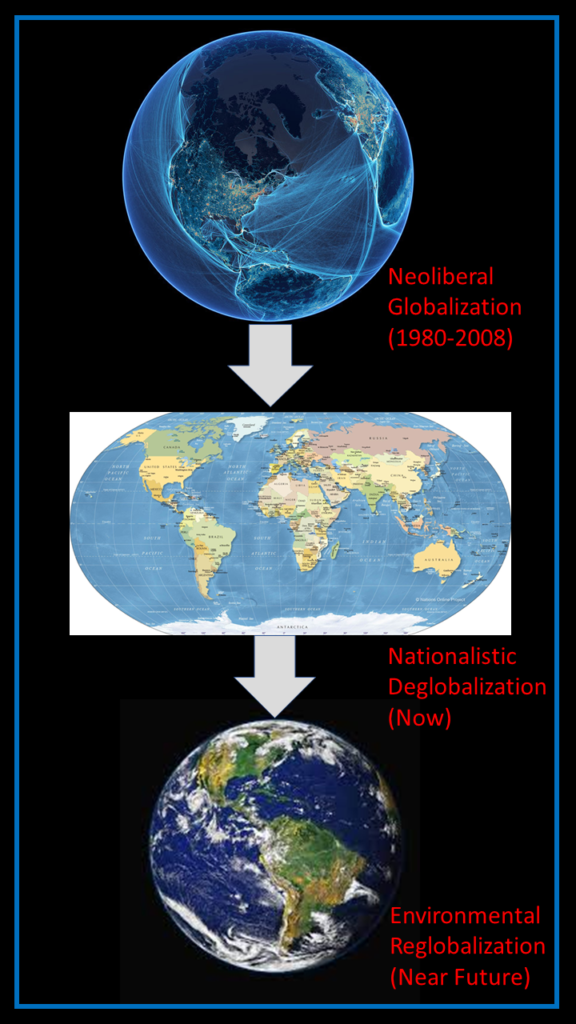

Deglobalization and Reglobalization

Global industrial roundwood demand is projected to rise by 50 per cent or more by 2050. To reduce loss of natural forests in the tropical zone, there must be a deglobalization of wood imports from tropical natural forests. This loss of logs (much of it illegal in any case) could be compensated for to some degree by increasing production from certified planted forests in the boreal, temperate, and tropical zones. Obviously, this new wood production should not come by way of converting intact primary forests to plantations.

Currently only 11% of the global forested area dedicated to wood production is plantation forests, yet that land provides around 33% of current industrial roundwood demand. Our world is going to need more high-yield forest plantations, along with the international trade that serves to match wood supply and demand (reglobalization).

Conclusion

The technosphere consumes a vast quantity of wood; where it comes from and how it is harvested matters greatly to the possibility of global sustainability. If unsustainable logging in primary forests was shut down, and compensatory increases in wood production were created from planted forests, sustainably managed forests could conceivably provide the current global demand for wood. Certification of managed forests and forest products is a key mechanism for halting entries into remaining natural forests, which better provide a variety of other ecosystem services.