David P. Turner / February 16, 2020

The peer-reviewed literature and the popular media

today abound with concern about human-induced global environmental change. Articles often argue that global scale

problems require global scale solutions: humanity is causing the problem and

“we” must rapidly implement solutions. Environmental

psychologists have found that people who sympathize with or identify with a

group are energized to support its cause.

Can a majority of human beings identify with humanity in a way that

motivates collective change towards global sustainability?

Let’s consider several key constraining factors and

unifying factors relevant to making humanity a “we” with respect to global

environmental change.

Constraining Factors

Notable sociopolitical factors that impede global

solidarity include the following.

1. Climate

Injustice among Nations

In the process of their development, the most

developed countries burned through a vast amount of fossil fuel and harvested a

large proportion of their primary forests, hence causing most of the observed rise

in atmospheric CO2 concentration.

But these countries are now asking the developing countries to share

equally in the effort to curtail global fossil fuel emissions and deforestation

to prevent further climate change. At

the same time, the impacts of climate change will tend to fall most heavily on

the developing countries because of their lower capacity for adaptation. The developing countries are pushing back on

the basis

of fairness, e.g. the outcome of the Kyoto

protocol (albeit now obsolete) was that only the developed countries

made commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

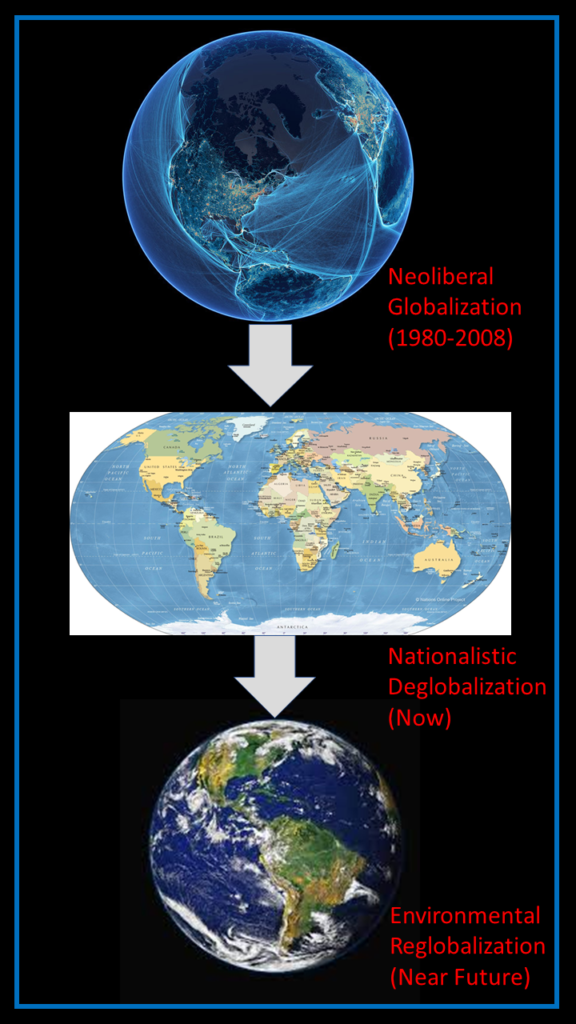

2. Rising Nationalism

Economists generally agree that economic globalization

has spurred the global economy and helped lift hundreds of millions of people

out of extreme poverty. However,

globalization of the labor market beginning around 1990 has also meant a large

transfer of manufacturing from the developed to the developing world – and with

it many jobs.

Likewise, immigration is helping millions of people a

year find a better life by leaving behind political corruption, resource

scarcity, and environmental disasters.

Unfortunately, one effect of economic globalization

and mass immigration has been political backlash within developed countries in

the form of populism and nationalism. Hypersensitivity

to loss of national sovereignty is not conducive to international agreements to

address global environmental change issues.

3. Climate

Science Skeptics

Although the global scientific community is broadly in

consensus about the human causes of climate warming and other global

environmental change problems, the rest of the world is more divided. Most people in the U.S. accept that the

global climate is changing, but only

about half accept the scientific consensus that climate warming is caused by

human actions. Sources

of skepticism about climate science include religious beliefs and vested

interests.

4. Economic

Inequality

Wealth

inequality, both within nations and

among them, is a pervasive feature of the global

economy. The rich end of the wealth

distribution contributes to the vested interests problem as just noted. At the poor end of the wealth distribution,

the hierarchy of needs discourages concern for the environment; solidarity with

the fight against climate change is a luxury when you are starving.

These four constraining factors are deeply rooted and

are only the head of a list that would also include competition for limited

natural resources and geopolitical conflict.

It is daunting to think about overcoming these obstacles to a “we” that

includes all of humanity. There are

substantive ongoing research and applied efforts (not documented here) to

overcome them, but in a general way let’s consider some equally significant factors

that may help foster a global “we”.

Unifying Factors

The following rather disparate set of factors supply

some hope for human unification under the banner of environmental concern.

1. Our Genetic Heritage

Humans are social creatures. Sociobiologists, such as Harvard Professor

E.O. Wilson, have argued that many of our social impulses are genetically

based. We have an instinctual propensity

to identify with a particular social group, and to draw a distinction between

that group (us) and outsiders (them).

The average ingroup size during the hunter/gatherer phase of human

evolution, which largely shaped our social instincts, is believed to have been

about 30 people. Remarkably, the size of

the social group that humans identify with has vastly expanded over historical

time − from the level of tribe, to the level of village, empire, and the modern

nation-state. Conceivably, that capacity

could be extended to the global scale: we

might all eventually consider ourselves citizens of a planetary civilization.

The historical expansion of social group size was

driven in part by military

considerations −

the need to have a larger army than your neighbor. Obviously, this rationale breaks down at the

global scale, but a distinct possibility for inspiring global solidarity is the

looming threat of global environmental change.

Note that being a citizen of the world does not

require rejecting one’s local or national culture. Multiple

sources of identity could include being an autonomous

individual, being a member of various ingroups, and being a member of humanity

in its entirety.

2. The Advance

of Earth System Science

A conspicuous general trend favorable to achieving a

collective sense of responsibility for managing human impacts on the Earth

system is growth in our scientific understanding of the Earth system. From studies of the geologic record, scientists

know that Earth’s climate has varied widely, from cool “snowball” Earth phases

to relatively warm “hothouse” Earth phases.

Greenhouse gas concentrations have consistently been an important driver

of global climate change, which gives scientists confidence that as greenhouse

gas concentrations rise, Earth’s climate will warm.

The scientific community also has expansive monitoring

networks that reveal the exponentially

rising curves for metrics such as the atmospheric CO2

concentration. Earth system models that

simulate Earth’s future show the dangers of Business-as-Usual scenarios of

resource use, as well as the benefits of specific mitigation measures. At the request of the United Nations, the global scientific community

periodically assembles the most recent research about climate change, the

prospects for mitigation (i.e. reduction of greenhouse gas concentrations), and

the possibilities for adaptation.

If improved understanding of the human environmental

predicament can filter down to the global billions, we might hope for a

strengthening support for collective action.

3. The Evolution

of the Technosphere

The technosphere

is a new global-scale part of the Earth system.

It joins the pre-existing geosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and

biosphere. However, just as the

evolution of the biosphere was a major disturbance to the early Earth system,

the evolution of the technosphere is proving to be disruptive to the

contemporary Earth system.

Around 2.3 billion years ago, cyanobacteria evolved

that could split water molecules (H2O) in the process of

photosynthesis. The resulting oxygen (O2)

began to accumulate in the atmosphere, radically changing atmospheric

chemistry. Oxygen was toxic to many

existing life forms, but eventually micro-organisms capable of using oxygen in

the process of respiration evolved, which in time led to the evolution of multicellular

organisms (and eventually to us).

In the case of technosphere evolution, a process that

emits excessive amounts of CO2 (combustion of fossil fuels) has

arisen, which is altering the global climate and ocean chemistry in a way than

may be toxic to many existing life forms.

One potential solution is that the technosphere can further evolve (by

way of cultural evolution) to subsist on renewable energy rather than

combustion of fossil fuels, thus moderating its influence on the atmosphere,

hydrosphere, and biosphere.

A characteristic feature of technosphere

evolution is ever more elaborate means of transportation and

telecommunications. These capabilities –

especially the on-going buildout of the Internet – allow for increased

integration across the technosphere and tighter coupling of the technosphere

with the rest of the Earth system. Sharing

results of environmental monitoring in its many dimensions over

the telecommunications network can help with creating and maintaining

sustainable natural resource management schemes.

Through the popular news and social media, nearly

everyone in the world can learn about events such as regional droughts and

catastrophic forest fires that are associated with climate change. It is thus becoming easier to have a common frame

of reference among all humans about the state of the planet.

There is not yet anything like a global consciousness

that coordinates across the whole technosphere.

However, the Internet is facilitating the emergence of a global

brain type entity. One

indication of what the nascent global brain is thinking about is the relative frequencies

of different search terms on Google.

Interestingly, in the algorithms that determine the response to search

engine queries, a high frequency of previous usage for a relevant web site

makes that site more likely to reach the top of the response list. That process is evocative of learning, i.e.

reinforcement through repetition. Similarly,

the Amygdala

Project monitors Twitter hashtags. They are classified according to emotional

tone, and a running visual summation gives a sense of the collective emotional

state (of the Twitterers). Advances in artificial

intelligence and quantum computing may soon improve the

module in the global brain that simulates the future of the Earth system.

4. The

Expanding Domain of Human Moral Concern

In “The Slow Creation of Humanity”, psychologist Sam McFarland recounts the history of the human rights movement. Writer H.G. Wells, humanitarian Eleanor Roosevelt, and others have helped develop the rationale and legal basis for including all human beings in our “circles of compassion” (Einstein’s term). The concept of rights has now begun to be legally extended to Nature (in Ecuador) and specifically to Earth (in Bolivia). Since protecting the rights of Earth (e.g. to be free of pollution) clearly requires that humans work collectively, we come to an incentive for global human solidarity.

Again, these four unifying factors are only the start

of a list that might also include global improvements in education, as well as

growth in the activities of global non-governmental environmental

organizations.

Conclusions

The field of Earth

system science is producing an increasingly clear

understanding of the human predicament with respect to global environmental

change. Scientist know what is happening

to the global environment, what is likely to happen in the future under

Business-as-Usual assumptions, and to some degree, what must change to avert an

environmental catastrophe.

The process of changing the trajectory of the Earth

system cannot be done unilaterally. From the top down, an important step will be

genesis or reform of the institutions of global governance – including institutions

concerned with the political,

economic,

and environmental dimensions

of governance. This is a task for a

generation of researchers, political leaders, and diplomats. From the bottom up, individuals must be

brought around as adults, and brought up as children, to adopt an identity that

includes global citizenship and associated responsibilities for the global

environment. This is a task for a

generation of educators, religious leaders, and business leaders.

If “we” human dwellers on Earth don’t gain a collective identity and begin to better manage the course of technosphere evolution, then we may no longer thrive on this planet.

Recommended Audio/Video, Mother Earth, Neil Young