David P. Turner / March 8, 2024

In the jargon of systems theory, a positive feedback means that a change in a system initiates other changes within the system that amplify the original change.

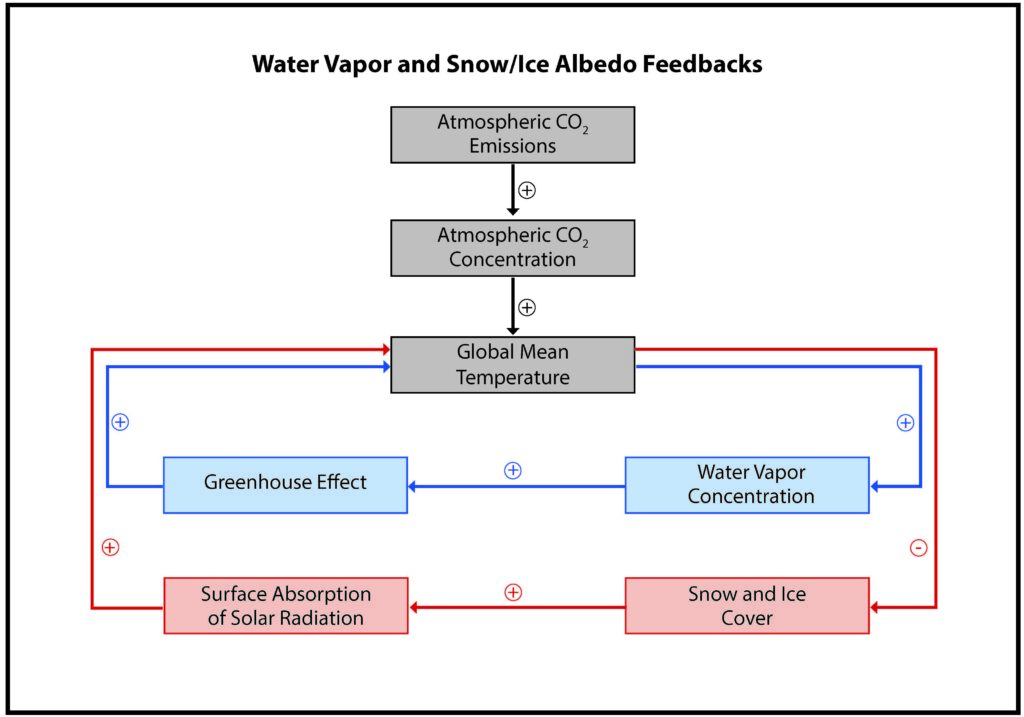

A clear example in the Earth system is the water vapor feedback: as the atmosphere warms (e.g. from increasing CO2) it can hold more water vapor (mostly evaporated from the ocean), and since water vapor itself is a greenhouse gas, the atmosphere warms further (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The water vapor (blue loop) and snow/ice albedo (red loop) feedbacks. Climate warming induced by anthropogenic CO2 emissions drives changes in the hydrosphere and cryosphere that amplify the warming. A plus sign means causes to increase and a minus sign mean causes to decrease. Image Credit: David Turner and Monica Whipple. Figure appeared originally in the Technosphere Respiration Feedback blog post.

Positive feedbacks are generally considered destabilizing to a system, potentially pushing it into a new state. Negative feedbacks aremore familiar, e.g. the furnace/thermostat cycle in home heating; they tend to stabilize a system.

The Earth system has significant negative feedbacks that have helped keep global mean temperature in a habitable range over its 4-billion-year existence. However, these feedbacks (e.g. the rock weathering thermostat) operate at a geologic time scale, and are thus not going to save humanity from the vast geophysical experiment that we began by burning fossil fuels and boosting atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases.

We need something faster. Hence, it is worth identifying and perhaps cultivating various positive feedback mechanisms that could support global sustainability. Here, I’ll consider three varieties of positive feedback loops that might help us.

Type 1. Psycho-social Positive Feedback Loops.

Humans have various cognitive biases, meaning our decisions are sometimes subject to unconscious tweaking. These tweaking tendencies have genetic as well as experiential origins, and may or may not be helpful in any given decision. Prestige bias, under which we are drawn to believe and emulate individuals who have achieved high status in our society, is an example.

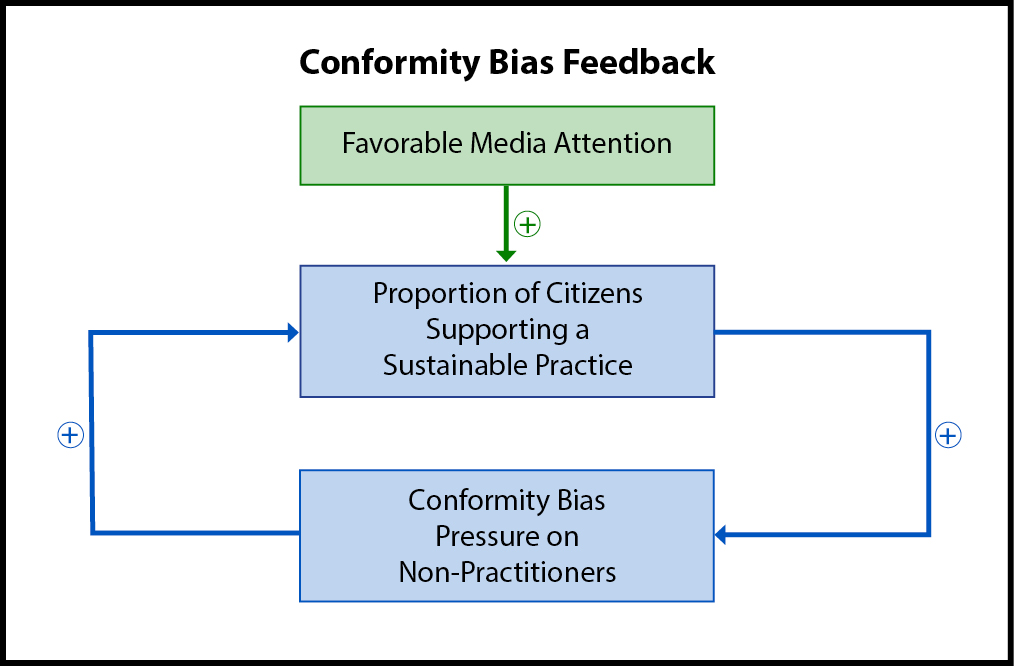

A cognitive bias that might help the spread of sustainability principles and practices is the conformity bias. As the name suggests, we tend to adopt ideas and practices that are already embraced by a significant proportion, or the majority, of our society. The positive feedback comes in because converts increase the proportion of the society that are believers, which strengthens the pressure on nonbelievers to conform.

Figure 2. Conformity Bias Positive Feedback Loop. Image Credit: David Turner and Monica Whipple.

The history of social norms and behaviors related to littering and paper recycling show evidence of conformity bias kicking in at some point.

Now that greater than 50% of Americans believe that climate change is for real, conformity bias may help enlarge the pool of believers, and hence the support for relevant policy changes.

Type 2. Technical-economic Positive Feedback Loops.

As new technologies become more widely adopted, the associated manufacturers begin to benefit from economies of scale, i.e. the marginal cost of production comes down as usage increases because larger production facilities are typically more efficient than smaller ones. More efficient production means that the product can be offered at a lower price, and hence demand will likely increase. This positive feedback loop can lead to rapid growth in product use.

An essential requirement for mitigating climate change will be conversion of the power sector from fossil fuel to renewable sources of energy. This conversion is ongoing and is benefitting from economies of scale. Installation of solar and wind power generators is expanding rapidly, in part because the economics are beginning to favor these sources over coal-fired plants. The cost of installed solar panels and wind turbines has decreased over time because of economies of scale and rapid technical advances. Hence, a virtuous cycle of more installations favors more decisions to go with renewables.

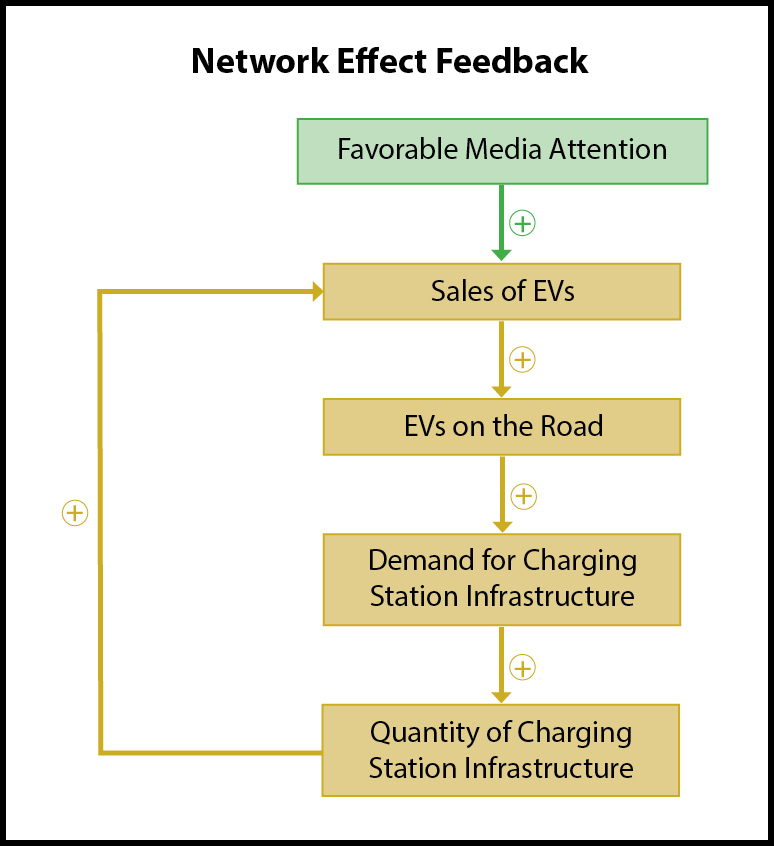

A second powerful technology-oriented positive feedback involves “network effects”. Here, as a new technology becomes more widely utilized, its value to the user increases, and more users are recruited. The spread of the telephone is the classic example.

Figure 3. Example of a Network Effect Positive Feedback Loop. Image Credit: David Turner and Monica Whipple.

The network effect is readily applicable to the proliferation of electric vehicles (EVs). The replacement of internal combustion engine powered vehicles with EVs is widely advocated to mitigate climate change. This transition has started, and is fortunately accelerating because of positive feedbacks. One feedback loop is that as more EVs enter the market, the economic incentives to build more charging stations has increased. More charging stations makes it easier to take long trips, which reduces range anxiety and incentivizes drivers to purchase EVs rather that gas powered vehicles.

Type 3. Socio-cultural Niche Construction Loops

Cultural evolution is the process by which the beliefs and practices of individuals and groups of various sizes change over time. At the level of group selection, particular ideas and group practices may strengthen the group when faced with intergroup competition (e.g. intertribal warfare).

There are many group traits that are shaped by cultural group selection; for analytical purposes we can divide them into three types: sociological, technical, and ecological (Table 1, also below). It is the constellation of these traits, including how they influence each other, that determines the success of a group.

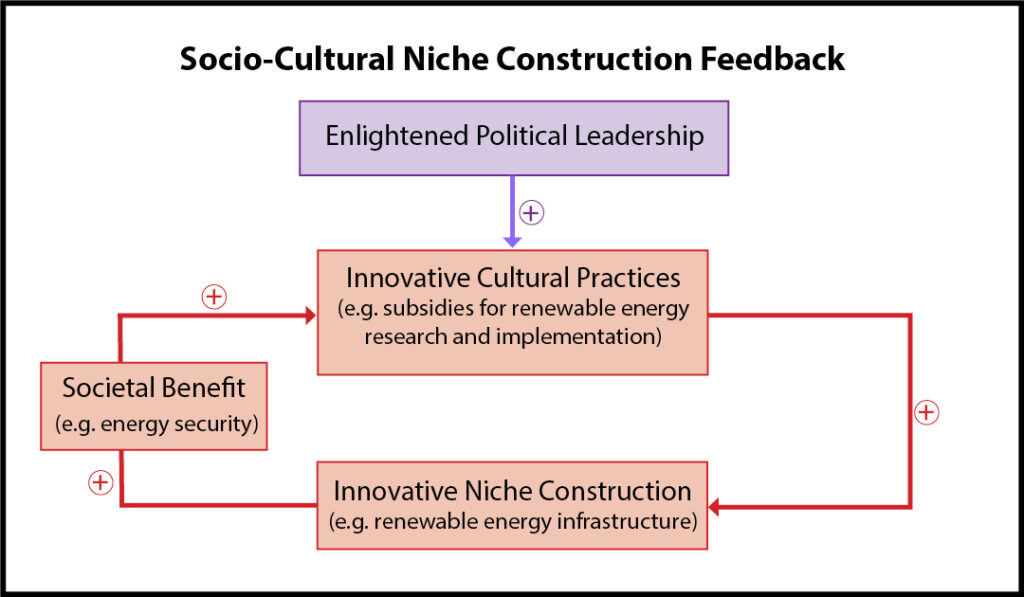

Socio-cultural niche construction refers to the idea that human societies alter their physical environment (e.g. the vegetation, the energy infrastructure) in ways that reciprocally influence how the society is structured and functions. Positive feedback loops among two or more of the group traits in Table 1 can result in rapid societal change.

If a group (e.g. a nation) invests (a sociological trait) in research and implementation of renewable energy technologies, the outcome may be a change in the mix of societal energy sources (a technical trait), which could result in cheaper and more reliable energy delivery to the society, which strengthens the society and encourages further investment in renewable energy sources. The societal choice of energy source also influences the ecological trait of local air quality. Improvement there would further strengthen the society and enhance group strength.

Figure 4. Example of a Socio-cultural Niche Construction Positive Feedback Loop. Image Credit: David Turner and Monica Whipple.

Conclusion

The various feedback loops reviewed here suggest that societal principles and policies are not simply top-down impositions on citizens. Rather, they can be significantly strengthened or weakened by reciprocal interactions with features of the social, technological, and ecological environment. To propel conformity bias regarding a particular value or technology, leaders and media can package it as a new social norm. To propel sustainable technologies that benefit from economies of scale and network effects, societies can subsidize early stages of their development. To foster revolutionary changes in technology (e.g. a renewable energy revolution), leaders must advocate for them based on the full range of their benefits to society.

These psychological and sociological considerations make the transdisciplinary aspects of Earth System Science ever more apparent.

Table 1. Examples of group traits that may interact to influence group selection.

Sociological Traits

Laws

Customs

Policies

Belief system (e.g. religion)

Type of political organization (e.g. tribe vs. nation state)

Type of military organization

Civic institutions

Technological Traits

Type of fuel for energy production

Form of transportation

Form of electronic communication

Ecological Traits

Local species composition

Local net primary production

Local air quality