David P. Turner / Edited 2/22/2026

Earth’s biodiversity is under siege by the global human enterprise (the technosphere). Most species will survive into the distant future, possibly a future in which the human population has shrunk, and the value of biodiversity is more widely appreciated. But many species will go extinct along the way.

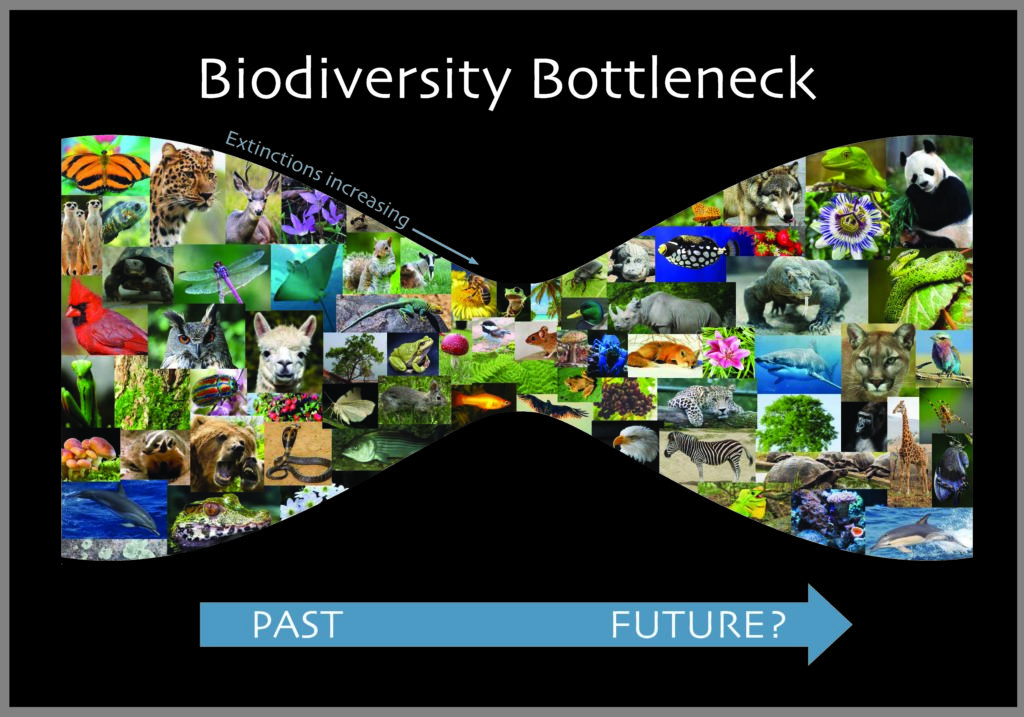

Biologist E.O. Wilson and others have evoked the image of a bottleneck in this context (Figure 1). A bottleneck implies a tightening of constraints on flow. In the case of the biodiversity bottleneck, flow refers to the survival of species through time.

As the future unfolds and the technosphere continues to grow, the possibilities for species to pass through the biodiversity bottleneck diminish. But there is a lot of room for maneuver here. A worthy project for humanity – especially over the next few decades − is to keep that bottleneck as wide as possible. After passing through it, global biodiversity may recover to some degree as the technosphere begins to weigh less heavily on the biosphere. It all depends on us.

Background

Evidence of human impacts on biodiversity surrounds us. Comparisons of current rates of extinction and those in the fossil record indicate that vertebrate species are now going extinct at a rate 100 or more times faster than is observed in most previous geologic periods. The human-driven Sixth Extinction began perhaps 50,000 years ago when primitive humans arrived on Australia and wiped out many prey species that were unfamiliar with the new bipedal super predator. Anthropologists refer to the “Pleistocene Overkill” to describe the wave of mammal extinctions that occurred when humans first crossed from Asia to North America about 15,000 years ago.

Modern humans continue to exterminate species directly by overhunting for food (e.g. the passenger pigeon) but also by widespread trafficking in wildlife and animal parts for food, as well as for medicinal and prestige purposes. Various plant species are also endangered, notably several tropical hardwoods known as rosewood. Sustained pressure on wildlife habitat from land use change and disruptions in geographic ranges caused by climate change adds further stress on top of overexploitation. Genetic variation within many species is shrinking as their populations and geographic ranges contract, hence reducing their capacity to survive environmental change (formally termed a population bottleneck).

In essence, the expansion of technosphere capital (the mass of human made objects) is consuming biosphere capital (the biodiversity and biomass of the biosphere). This loss of biodiversity − usually defined in terms of diversity of species and ecosystems − will likely continue over the coming decades. As noted, though, the magnitude of the loss will depend heavily on human decisions.

There are pragmatic, aesthetic, and ethical rationales for conserving Earth’s biodiversity. Conservationists argue that retaining biodiversity maintains the functional integrity of ecosystems, and hence the full array of their ecosystem services. Each species has a unique niche and contributes to ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling and recovery from disturbances. With respect to aesthetics, the earlier mentioned Professor Wilson has suggested that humans have genetically determined biophilia − we get spontaneous pleasure from interacting with diverse forms of life. The ethical argument is made strongly by the Deep Ecology movement. For supporters, there is no human exceptionalism – all species have an equal right to survive and prosper on this planet.

Given the multiple rationales for wishing to widen the biodiversity bottleneck, what collective actions (besides the overriding one of limiting climate change) can help? Scientists and policy experts have identified biodiversity-friendly practices such as reducing pesticide use, buying certified products, reducing invasive species, and reducing water pollution. But here are four others that have high relevance.

1. Stop Trafficking in Wildlife and Wild Animal Parts

The global trade in wild animals and wild animal parts puts tremendous downward pressure on the populations of many species. Wild animals are commonly sold in Southeast Asian food markets despite laws against it. Tigers, rhinos, and pangolins continue to be poached for dubious medicinal purposes. Wild caught animals are sold as “bush meat” in parts of Africa and South America.

A global trade in live animals intended as pets also flourishes. Millions of songbirds are collected every year in the primary forests of Indonesia and sold as pets or trained as contestants in bird song competitions. Tropical fish are collected in the wild for marketing to aquarium owners.

Multiple international agreements aim to stem wild animal trafficking, especially the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Under its auspices, national law enforcement agencies regularly confiscate illegal shipments of wild animals, animal parts, and wood from endangered tree species. However, these efforts face deep resistance for cultural and economic reasons.

A new brake on wild animal trafficking is fear of zoonotic pathogens. The SARS-CoV-2 virus that is causing the Covid-19 global pandemic likely jumped from a wild animal host to a human in a market where wild animals are sold illegally. New legislation passed in China limits sales of wild animal meat. Unfortunately, enforcement is spotty, and the new law still allows sales of wild animal parts for medicinal purposes. Sustained international pressure on wildlife traffickers is needed.

The Covid-19 pandemic is apparently impacting wildlife protection in other ways. Conservationists fear that the loss of the tourist ‘halo’ or proximity effect, because of Covid-19 shutdowns, will increase the incidence of poaching in nature reserves. Resumption of tourism would help in that regard.

2. Expand the Size and Number of Protected Areas

A key driver of declining biodiversity is habitat loss. To bring as many species as possible through the biodiversity bottleneck will require protection of representative areas for all unique types of ecosystems.

The Rewilding Movement has argued for creating protected areas that are large enough to support the whole complement of native species characteristic of each ecosystem type, along with the entire range of abiotic processes such as floods and fires that help maintain it.

Presently, about 15% of global land plus inland waters is protected to some degree. For the oceans within national jurisdictions, the figure is about 13%. Not all ecosystem types are represented. For many types of ecosystems, the current protected area is quite small relative to its original geographic distribution (e.g. the Atlantic rain forest in Brazil).

Aspirations for expanding the protected areas of land and ocean range from 17% of land to half of Earth as a whole (the latter courtesy of the illustrious Professor Wilson).

Protected area plans can be developed over large domains, e.g. the entire United States. These plans rely on integration of different managed lands such as wilderness areas, national parks, national forests, urban areas, and private reserves.

An international scientific advisory body (IPBES, Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) is dedicated to biodiversity assessment and conservation. Like the Intergovernmental panel on Climate Change, IPBES produces periodic assessments and examinations of policy options. IPBES is supported by member countries, including the U.S., and sustained national contributions are warranted.

In the private sector, land trust organizations such as The Nature Conservancy have as their key strategy the purchase of lands for conservation purposes; contributions are encouraged. Public/private conservation partnerships are proliferating; participants are welcomed.

3. Design Sustainable Cities

The proportion of the global population that lives in an urban setting recently passed the 50% mark and is expected to keep climbing in the coming decades. A potential benefit to biodiversity conservation lies in the land that is abandoned as people supported by subsistence agriculture and nomadic herding move to towns and cities. The freed-up land can potentially be repurposed in part or whole for wildlife conservation. An underlying assumption is that agricultural intensification can take up any slack in food production and keep everyone fed.

Urban greenbelt areas, parks, and gardens may serve directly as another assist to biodiversity conservation. They support native and alien species and could serve as refuges for plant and animal species that are extirpated regionally by climate change and land use change. Urban rivers and streams can likewise be managed to protect and support wildlife.

4. Strategically Increase Ecotourism

In theory, the local economic benefits of nature-based tourism inspire local conservation efforts. However, high tourist demand produces pressure to increase supply. More local economic development (e.g. hotels and restaurants) plus more intensive visitor utilization of natural resources may end up degrading local ecosystems. The research literature contains ecotourism case studies of successes, as well as failures.

Ecotourism narrowly defined refers to tourism that allows visitors to experience local wildlife and landscapes, creates incentives to protect those organisms and landscapes, and supports local communities. More ecotourism is probably not appropriate in many places where it already exists because capacity is limited. Rather, it is needed where wildlife is under threat and conservation incentives might be effective.

Building socio-ecological systems is an emerging route to local sustainability. These stakeholder groups optimally self-regulate to conserve the economic health and ecological health of the local environment. Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom has developed principles for structuring and operating these groups. Monitoring the social, economic, and ecological dimensions of sustainability is a key requirement for successful ecotourism management.

Ecotourism, and tourism more generally, cannot be discussed in the context of biodiversity conservation without considering their global scale impacts. As noted, climate change is a threat to biodiversity, and the carbon footprint of tourism is estimated to be 8% of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Air travel is the foundation for much tourism, but it is especially difficult to decarbonize. Short hop electric airplanes and long-haul flights powered by renewable energy based liquid fuels are technically feasible. They could replace fossil fuel powered flights, but more government supported research is needed, and air travelers must be willing to pay an increased fare as these fuels are brought online. Airline-associated carbon offset programs − although varying in effectiveness and not a permanent solution − contribute significantly to biodiversity conservation. They help expand protected area and, by sequestering carbon, help slow climate change.

Conclusion

The human capacity to extinguish other species on this planet, and to pervasively alter wildlife habitat, means that we are in many ways responsible for which species and ecosystems will survive. As we move through peak human population this century and begin to more purposefully manage our impacts on Earth’s biota, let’s keep the biodiversity bottleneck of our own making as wide open as possible. Progress towards that goal would be both pragmatic and gratifying.

Recommended Audio/Video

Video version of this blog post (Google NotebookLM)