David P. Turner / August 12, 2023

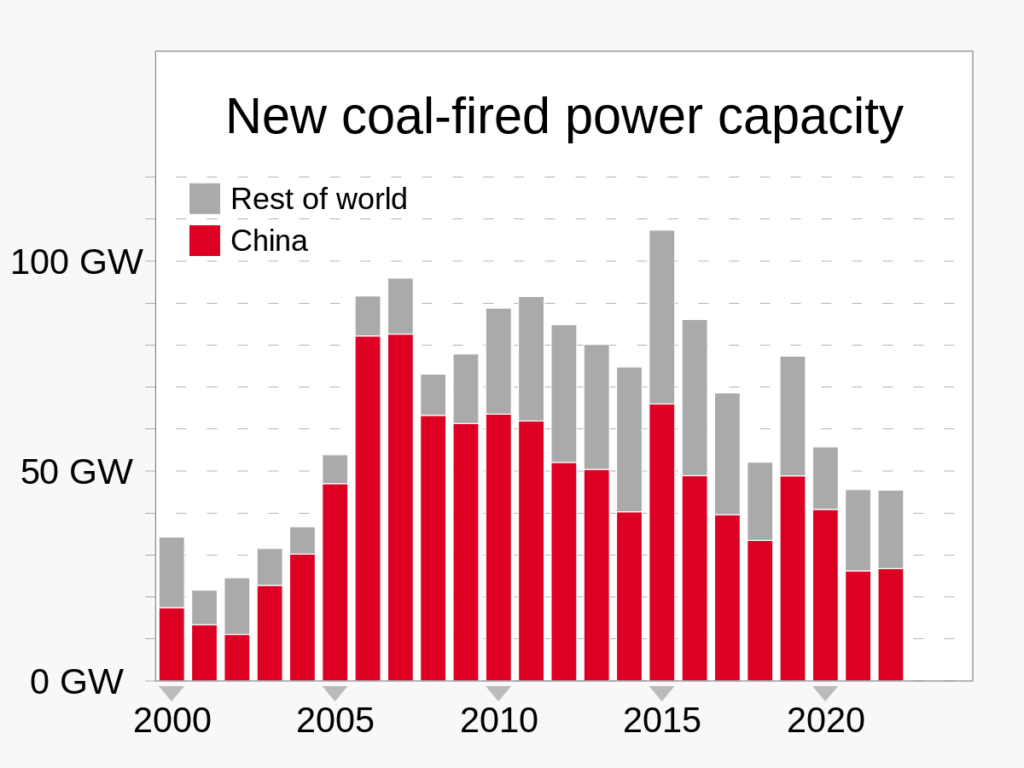

Figure 1. Annual additions of coal-fired electricity generation in recent years. Image Credit.

The rash of extreme weather events and associated impacts on humans around the world in recent years (especially 2023) is setting the stage for radical societal changes at the local and global scale with respect to climate change mitigation efforts. One recognizable step-change in that direction would be a planet-wide cessation in the issuing of permits to build new coal-fired power plants.

Extreme weather events (droughts, heat waves, fires, and floods) are very much in the news recently everywhere on the planet. Within the scientific community, these events are understood as part of normal weather variability, but also as attributable in part to on-going anthropogenic climate warming. This year (2023) is proving to be especially prone to extreme weather events because of an extra boost of warming associated with an El Nino event.

Globally, climate scientists suggest that 85% of people have suffered from extreme weather events that are partially attributed to climate change.

Social science research has shown that people respond markedly to their personal experience with weather events. In the U.S., polls (2022) find that 71% of Americans say their community has experienced an extreme weather event in the last 12 months and 80% of those respondents believe climate change contributed at least in some measure to the cause. In China and India, recent polls suggest strong awareness about the climate change issue and support for governmental mitigation policies.

Admittedly, awareness of the issue is much lower elsewhere. Some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have relatively high proportions of inhabitants that have “never heard of” climate change.

Nevertheless, billions of people around the world are making the connection between their personal experience of an extreme weather event and climate change. Perhaps a new level of political support for mitigation efforts will emerge?

The concept of tipping points is common in the climate change literature, i.e. that distinct large-scale processes such as the melting of the Greenland ice sheet eventually reach a point where strong positive (amplifying) feedbacks are engaged and the process becomes irreversible (on a human timescale). The concept has also begun to be applied to changes in social systems. Given widespread changes in personal views about climate change, and perhaps appropriate societal interventions, particular societies and ultimately the global society may tip into a strong climate change mitigation stance.

A clear step-change in the global climate change mitigation effort would be a planet-wide cessation of permits for building new coal-fired electricity generating plants. Coal emissions contribute about 40% to global fossil fuel emissions.

Tremendous momentum has already built up in that direction based on anti-coal environmentalism and the improving cost differential between coal power and other energy sources (primarily natural gas and renewables). The U.S. and E.U. do not formally prohibit new coal plants but few have been built in recent years.

The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative are no longer supporting construction of new coal-burning facilities and many countries have made commitments in their Nationally Determined Contribution statements that will require reduction in the burning of coal.

Remarkably, India has recently announced consideration of a policy to prohibit planning of new coal-fired plants for at least the next 5 years.

China is still permitting and building about 2 coal-fired power plants per week. It is no doubt a big ask for China to adopt a no-new-coal-plants policy. However, the country is suffering significantly from extreme weather events, from the negative effects of air pollution from coal combustion, and from the interaction of the those two factors. And China leads the world in production of renewable energy.

The autocratic style government in China is not conducive to bottom-up social tipping dynamics, but how the Zero-Covid policy was dropped is an interesting case study in social change. Rumblings within the bureaucracy and multi-city protests appear to have influenced Xi Jinping to make the radical policy shift. Given its massive contribution to the global total of new coal plants coming on line (Figure 1), if China stopped issuing building permits, the battle would be nearly won.

Two caveats to ending coal-fired power plant construction should be considered. First is that the global demand for electricity will likely increase in the future because of 1) growth in the global population and increased per capita energy use in the developing world, 2) increasing demand from the conversion to electricity powered vehicles, and 3) wide application of AI technology. To generate that energy from non-coal sources will be challenging but feasible. The second consideration is the possibility of Carbon Capture and Storage, i.e. continuing to burn coal but capturing the associated CO2 emissions and sequestering them belowground. This technological fix sounds good in theory but thus far decades of research and pilot studies do not support that it can be economically implemented at scale.

Across all of humanity, cultural differences tend to build silos around each society – especially differences in language, religion, and degree of technological development. That isolation has diminished over the course of human development to this point, and with the advent of the Anthropocene we can begin to see humanity as a unified whole and as capable of working collaboratively on global environmental change issues.

When the world does achieve consensus on ending the construction of new coal power plants, it will be a step-change in the global climate change mitigation effort. It will also signal a step towards the emergence of a collective humanity, an indication that “we” can agree on, and implement, a path to a sustainable future on Earth.