By Will Kennerley, Faculty Research Assistant, OSU Seabird Oceanography Lab

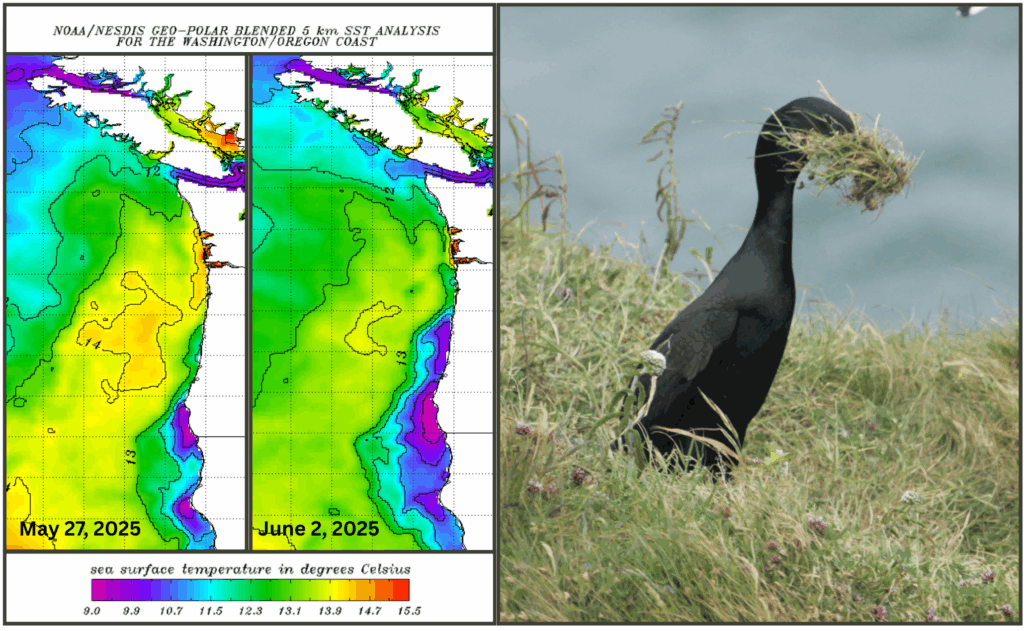

The cliffs and offshore rocks of Yaquina Head have quieted down now after another summer. The 2025 seabird monitoring season wrapped up around the start of September with the fledging of our final monitoring nests. The last Common Murre chicks fledged around the 20th of August and the cormorant creches were thinning out by Labor Day. All in all, it was a successfully average year – all four of our monitored species (COMU, PECO, BRAC, and WEGU) fledged chicks at or near average rates. This is a significant improvement from the 2024 season for Common Murres and Pelagic Cormorants, and a slight decrease for Brandt’s Cormorants and Western Gulls. Ocean conditions, likewise, appeared fairly typical, with mostly average nearshore sea surface temperatures during most of the breeding season and an ENSO neutral North Pacific (now transitioning to La Niña).

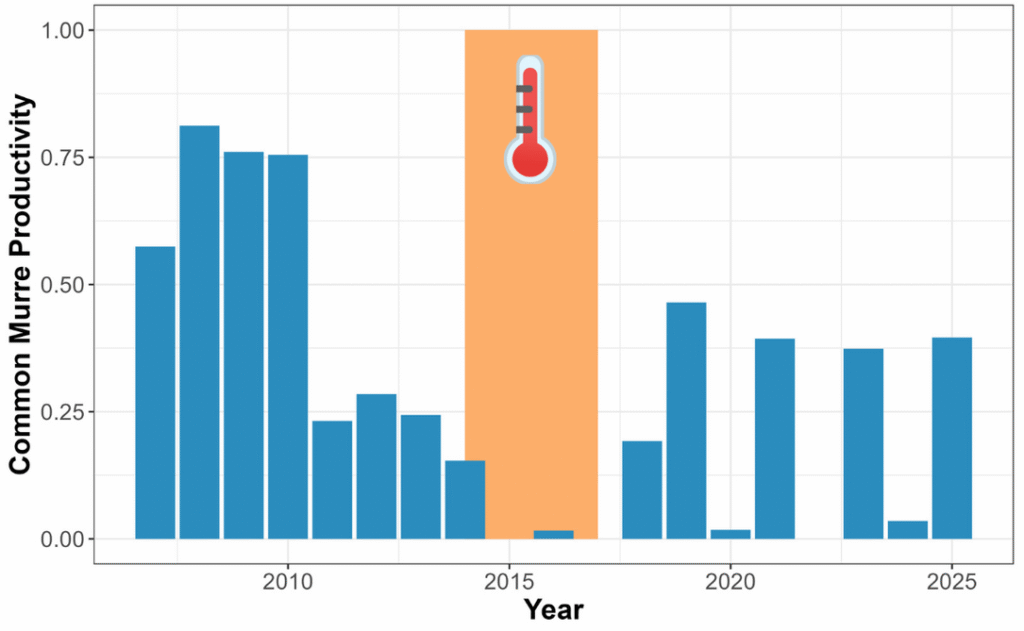

Perhaps most interestingly, our prediction that murres would breed successfully proved correct. Roughly since the 2014-2016 NE Pacific Marine Heatwave (“the Blob”), the murres at Yaquina Head have been successfully raising chicks each odd-numbered year, and failing in even-numbered years. The reasoning for this pattern remains hard to confirm, but we suspect reduced prey availability – perhaps driven by biennial patterns in pink salmon populations – leads to murres entering the breeding period in poorer body condition.

Figure 1. Common Murre productivity (mean chicks produced per nesting attempt) at Yaquina Head, 2007-2025. Note that productivity since “the Blob” (shaded orange) has been highly variable, with exceptionally low productivity during even-numbered years.

Part of this response likely involves the eagles at Yaquina Head. Predation and disturbance from Bald Eagles leads to murres temporarily abandoning their nests, inviting nest predation by local Western Gulls and corvids. This dynamic is especially critical during egg laying as nests first get established on the colony. In years when the colony fails, eggs are eaten nearly as quickly as they are laid. During successful years, eagles still cause disturbances, but murres appear to be more resilient and less likely to leave their nests en masse. This process is hard for us to document, especially in the months before egg laying. Next time you visit Yaquina Head, please keep an eye out for our new photo point exhibit (soon to be installed on the stairway down to the tidepools) and send us a picture following the posted instructions! This photo point is a part of CoastSnap and we are hoping to use the photographs to better understand how early season colony attendance, especially from February through May, translates to Common Murre breeding success.

Figure 2. Early-season predator disturbances can keep murres on the water, away from prospecting and egg-laying at the colony, potentially delaying reproduction and impacting overall productivity. We’re hopeful that community science efforts like CoastSnap can help us better understand the effect of murre colony attendance patterns.

This year, while we observed 47 predator-caused disturbances to the murres, the scale of these disturbances (% of the colony cleared and overall duration of the disturbance) was less than the five-year average. Paired with another year of seemingly reliable prey sources (predominantly smelt), this led to the Yaquina Head murres hatching 49% of the eggs they laid and fledging 50% of chicks. Overall, this led to an average productivity (eggs fledged per nest, averaged across our plots) of 0.40, well above our 10-year average (0.19 chicks fledged/nest) but almost precisely the average of our last three odd-numbered years (0.41 chicks fledged/nest).

This odd-even pattern of murre reproduction does not hold at the nearby Pirate Cove colony in Depoe Bay, where eagle disturbance is generally less. Murre productivity there was 0.76 chicks fledged/nest and productivity is typically more consistent than at Yaquina Head. This supports the idea that the pattern of murre productivity might well be driven by a bottom-up factor but is likely mediated by predator disturbance.

Figure 3. Murres have successfully bred consistently at the nearby Pirate Cove colony, even on flat, exposed areas of the colony. This is due to lower rates of disturbance from Bald Eagles and other predators at this colony than at Yaquina Head, despite lying just 10 miles north. This suggests predator disturbance interacts with bottom-up factors to create the odd-even pattern of murre productivity being observed at Yaquina Head but not at Pirate Cove.

We’re hopeful that additional monitoring data will help reveal the causes of the intriguing odd-even year pattern of murre productivity. One new development at Pirate Cove is that we documented at least nine Pelagic Cormorant chicks being predated by Bald Eagles, despite generally lesser predator disturbance at this site. Is this the start of increasing eagle predation pressure here, too? Is there a reason the eagles here seem to be impacting the reproductive success of Pelagic Cormorants more than that of Common Murres? As often happens, additional data only leads to new questions, and we’re already looking forward to next year, hopeful that we’ll have a better understanding of the ever-changing top-down and bottom-up factors that influence seabird reproductive success.

As always, many, many, thanks to our various funders and supporters, including the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Science Foundation, Environment for the Americas, and the Friends of Yaquina Lighthouses.