During winter term 2025 Dr. Kara Ritzheimer’s History 310 (Historian’s Craft) students researched and wrote blog posts about OSU during WWII. The sources they consulted are listed at the end of each post. Students wrote on a variety of topics and we hope you appreciate their contributions as much as the staff at SCARC does!

Blog post written by August Gadbow

“Collegiate sports revolutionized campus life, turned institutions of higher education into athletic agencies, brought changes in the curriculum, and influenced administrative policy.”[i] The rise of college sports not only integrated athletics into university structures but also expanded their influence beyond academia. Legislators, university administrators, and even U.S. presidents recognized the role that collegiate athletics played in shaping national identity, fostering school spirit, and connecting colleges to the broader public. College athletic history is American history and a powerful tool for measuring the effects of world events. During the Second World War, college sports were severely disrupted, forcing universities to adapt their programs to the realities of wartime. Oregon State’s experience during this time gives insight into how the global crisis reshaped college athletic programs.

Oregon State College’s (OSC) Athletic Board Minutes from 1942-1943, used as a bookkeeping tool, provides a detailed account of how the college managed its athletic programs during the uncertainty of WWII. The minutes record important administrative discussions, including budget reports, letters between directors, sports schedules, and business decisions. The document’s tidy and straightforward format and to-the-point writing style suggest that it was intended for administrative use only, and used to track decisions and financial records. However, because the broader societal context was the US involvement in WWII, its pages are riddled with war-related issues including economic uncertainty, travel restrictions, and athlete shortages. The report provides useful insight into how OSC administrators dealt with the realities of wartime while trying to maintain the athletics program.

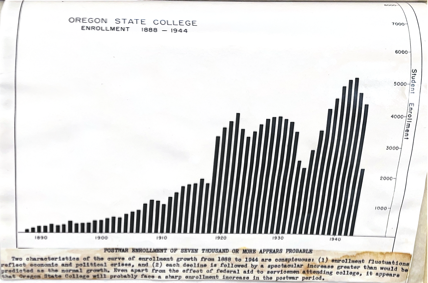

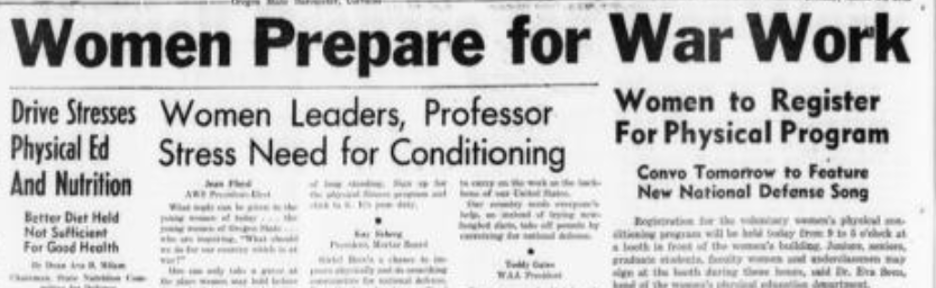

WWII forced Oregon State athletics to shift from traditional college competition to a model focused on adoption, survival, and military preparedness. During the war, OSC boasted a prominent ROTC program and had deep ties to the war effort; many competing athletes were also enrolled in its military programs. In August 1943, the US War Department banned training members of the military from participating in intercollegiate athletics, thereby disrupting all sports and most notably leading to the suspension of OSC’s football team until the end of the war.[ii] Despite this setback, the Oregon State athletics Administrative Council remained committed to student athletic programs, reaffirming in April 1944 that sports were an essential part of student life and long-term campus planning.[iii] While the majority of sports still did run at some capacity, financial uncertainty and the declining enrollment in the school led faculty members to be cautious about major athletic investments.[iv] During this time, Oregon State College athletics simply could not combat the setbacks of wartime. Understanding that its resources could also be useful elsewhere, OSC reshaped its approach to sports beyond competition. In 1942, the university’s women’s physical education programs greatly expanded, emphasizing health and fitness as patriotic duties in support of the war effort.[v] These changes, combined with ROTC athletes, added to OSC’s wartime efforts beyond STEM and agriculture.

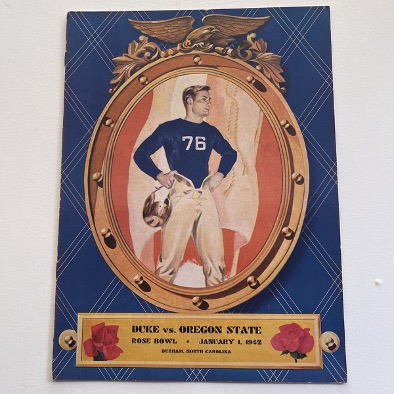

Athlete participation was limited, travel was restricted, and priorities were shifted towards the war effort. Oregon State’s athletic history during this time was greatly stunted. In 1942, students enrolled in the ROTC programs were not allowed to travel off campus.[vi] This led to much less success in away events for the school and also limited students’ abilities to be eligible for varsity letters and awards.[vii] Furthermore, this may have been the last time athletes were able to compete as students before being deployed to war. Those who were not enrolled in the military program also faced challenges pertaining to travel. Wartime restrictions led to the use of school-owned cars for transportation instead of the bus or train, whose prices were overinflated at the time. This decision was also supported by the war effort to reduce the number of people on public transport.[viii] Wartime fears made other schools weary of travel toward the West Coast, leading to the postponement and relocation of football games.[ix] Directly before the program’s temporary pause, OSCs competed against Duke in its first Rose Bowl appearance, taking place in Duke’s stadium in North Carolina, away from its usual location, Pasadena, California.[x] (Oregon State beat the undefeated Blue Devils 20-16 marking the team’s only Rose Bowl victory to date.) As the nation mobilized for war, OSC’s athletic department redirected financial resources to support the war, shifting its priorities from sports to national service. Funds from the previous Rose Bowl game were donated to the Red Cross along with investment into defense savings bonds by the athletic department.[xi] Oregon State athletics were dampened by WWII, athletes were suspended from competition, travel was severely limited, and their resources were directed elsewhere.

Scholarly sources on college athletics during WWII that are not football-oriented are limited. It’s reasonable to presume, however, that the problems Oregon State athletics faced were widespread among colleges throughout the nation. Like Oregon State, many college football programs could not continue to function during the war due to a “shortage of cars, tires, fuel, and students.”[xii] Low spectator turnout and the loss of top players due to enlistment gave universities little incentive to spend the money and time to continue to compete. By August 1942, nine months after the US entered the war, 52 colleges had paused football and some, including Gonzaga, Saint Mary’s, and NYU, cut it completely. A majority of these schools were located away from major metropolitan areas and relied on spectators to travel, which was discouraged during wartime.[xiii] By 1943, over 200 schools, including Alabama, Michigan State, and Stanford, suspended their football programs until the end of the conflict. While civilian universities’ athletic departments struggled, in contrast, military academies teams and service teams dominated, benefiting from direct government support and unique advantages.[xiv] The US government believed that having strong football programs promoted morale within the ranks and boosted voluntary military recruitment. Military officials went to great lengths to maintain the prestige and appeal of military academies during the war. In 1942, President Roosevelt insisted that the historic Army vs. Navy game still take place despite many other games being cancelled and there being restrictions on nonessential travel. Furthermore, the matchup between West Point (Army) and Notre Dame was canceled due to Army officials’ fear that a bitter rivalry matchup between big Catholic schools would undermine Catholic support for Army. The Black Nights (Army) government connection even improved their recruiting systems. The head coach at the time, Earl Blaik, used West Point graduates around the country as scouts for the team. When the best high school players were determined, Blaik would ask members of Congress to appoint the athletes to the academy. These benefits did not fall short of results: during the war, Army boasted a seventy-seven percent win rate and won two undisputed titles.[xv] In modern college football, the chances of any military academy winning a national championship are close to none. World War II completely reshaped college football. While civilian universities like Oregon State battled the setbacks of wartime, military academies directly profited from it.

The study of college athletics is uniquely positioned to illustrate the effects of war. The war impacted tradition, competition, and national identity. The same men who represented their schools in football represented the nation in war. As college life was more broadly disordered by the war, OSC athletics was completely disrupted. Football was suspended, travel restrictions limited competition, and financial resources were redirected toward the war effort. The school campus, meant to be a hub of school spirit, became a place of military preparation, with sports doubling as physical training and athletes enlisting. The war didn’t just subdue and pause college athletics, it redefined their purpose, making schools like OSC adapt to wartime America.

[i] Guy Lewis, “The Beginning of Organized Collegiate Sport,” American Quarterly, 22, nr. 2 (Summer, 1970): 222-229.

[ii] “’World War II’ in Where’s Waldo? Exploring Waldo Hall History,” Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives Research Center (hereafter SCARC), https://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/waldo/wartime/wwii.

[iii] Administrative Council Minutes, April 20, 1942, SCARC, Administrative Council Records, Box-folder 2.4, Minutes.

[iv] Administrative Council Records, April 20, 1942.

[v] Brooklyn Blair, Grace Matteo, and Ruiqi Zhang, “Promoting Physical Health for Women at Oregon State College During World War II,” Oregon State University Special Collections Blog, February 8, 2024, https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/scarc/2024/02/08/promoting-physical-health-for-women-at-oregon-state-college-during-world-war-ii.

[vi] Letter to the athletic director regarding ROTC athletes, April 19 1943, Intercollegiate Athletic Board Minutes 1942-1943,8, SCARC, Intercollegiate Athletic Records, RG 007, Box 1.

[vii] A track coach’s recommendation for an athlete to earn a 2-stripe award even though he did not compete in the required amount of events do to army regulations, May 25, 1943, SCARC, Intercollegiate Athletic Board Minutes 1942-1943, 2, Intercollegiate Athletic Records (RG 007), Box 1,

[viii]OSC Athletic Director to a Member of the Corvallis Ration Board, April 15, 1943, Intercollegiate Athletic Board Minutes, 1942–1943, 9–10,SCARC, Intercollegiate Athletic Records (RG 007), Box 1.

[ix]Michigan State Athletic Director letter from 1942 requesting postponement of a football game due to fears of traveling to the West Coast, Intercollegiate Athletic Board Minutes, 1942–1943, 15, SCARC, Intercollegiate Athletic Records (RG 007), Box 1.

[x] Oregon Stater, February 1942, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx71bk57j.

[xi] Letter to the Vice chairman of the Red Cross, March 9 1943, Intercollegiate Athletic Board Minutes 1942-1943, 31 SCARC, Intercollegiate Athletic Records, RG 007, Box 1.

[xii] Joseph Paul Vasquez III, “America and the Garrison Stadium: How the US Armed Forces Shaped College Football,” Armed Forces & Society 38, no. 3 (2011), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0095327X11426255

[xiii] Brenden Welper, “Like 2020, College Football Was Very Different During World War II,” NCAA.com, October 7, 2020, https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/2020-09-21/2020-college-football-was-very-different-during-world-war-ii.

[xiv] The US War department banned training members of the military from participating in intercollegiate athletics. See: “No Football at OSC this Year,” Oregon State Yank, November 1943, 3, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719t248?locale=en

[xv] Joseph Paul Vasquez, III, “America and the Garrison Stadium: How the US Armed Forces Shaped College Football,” Armed Forces & Society, 38 no. 3 (2011), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0095327X11426255.