This article was written for the regular column that I submit to the Hardy Plant Society of Oregon (HPSO) Quarterly Magazine. I am grateful to the team at HPSO for their editorial skills and feedback, that always improve what I write.

No Mow May is an initiative that was started in 2019 by Plantlife, a non-profit that works to restore meadow habitats in the United Kingdom. Their annual campaign called on garden owners and greenspace managers to cease mowing in the month of May, in order to move lawn-dominated yards towards a more natural approach. The movement quickly spread to other regions of the globe, as an easy and feel-good measure that almost any land manager could take to promote biodiversity and protect pollinators. In the United States, Bee City USA adopted the No Mow May campaign, which they also refer to as Mow Less Spring, as a way to conserve native pollinators.

There is some science to support the notion that less-intensely managed lawns benefits biodiversity. Our lab group even wrote about it in a blog post on No Mow May, including sharing a meta-analysis of 14 studies from North America and Europe showed that plant diversity and invertebrate diversity increased in lawns, as mowing intensity decreased [1]. However, several studies included in this review had mowing treatments that are not generally practical for most residential yards. Some studies compared lawns mowed once per week to lawns that were mowed once per year, for example. One of the few studies that compared mowing frequencies that approximate real world conditions was conducted in Springfield, Massachusetts [2]. In this study, Dr. Susannah Lermann and colleagues compared bee abundance and diversity from yards mowed every week, every two weeks, and every three weeks. Lawns mowed every three weeks had 2.5X more lawn flowers than other lawns. Interestingly, lawns mowed every two weeks had the highest bee abundance, but lowest bee species richness. The authors speculate that the higher grass height of the three-week mowed lawns covered lawn flowers, and made them less accessible to many bees. The higher lawn height also made the three-week mowed lawns less acceptable to nearby neighbors, leading the authors to suggest that a ‘two-week regime might reconcile homeowner ideas with pollinator habitat’.

That brings us back to No Mow May, and whether or not there is science to support the idea that not mowing for an entire month might benefit pollinators. In 2020 (soon after the start and spread of No Mow May) Del Toro and Ribbons published a paper that suggested that households that observed No Mow May had three times more bee species and five times higher bee abundance than spaces that were regularly mowed [3]. The results were highlighted in a New York Times story [4], and resulted in a change in the City of Appleton code that suspended an 8” lawn height restriction for the month of May, via a 6-3 split vote for and against the resolution [5]. Israel Del Toro, lead author of the study, was elected to Appleton’s Common Council, soon after leading the effort to adopt the resolution. By 2022, an additional 25 U.S. cities had followed suit [6], with their own declarations in support of No Mow May.

As the No Mow May movement grew, so did controversy surrounding the Del Toro and Ribbons study. Bee taxonomist Zach Portman noted serious issues with the bees identified in the study. Horticulture Professor Bert Cregg noted that the study was confounded, by comparing home lawns that were not mowed to park spaces that were mowed. With this experimental design, it is impossible for the authors to disentangle the effects of mowing (e.g. mowed or not mowed) from the effects of habitat type (e.g. home lawn versus park). In November of 2022, the authors retracted their study ‘after finding several potential inconsistencies in data handling and reporting’. After the retraction, the City of Appleton considered a resolution to eliminate No Mow May, claiming that the program lacks scientific backing. However, this resolution did not pass [7].

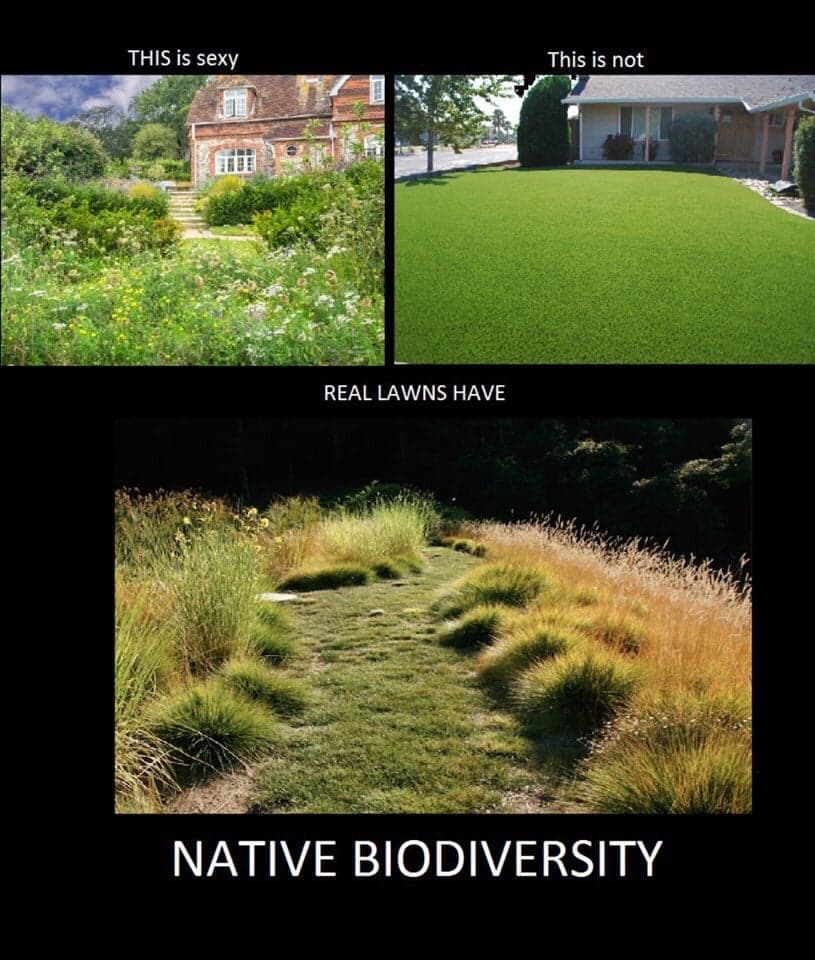

What is a science-informed gardener to do, amidst confusing and sometimes conflicting messaging related to pollinator conservation in a yard? First, note that science self-corrects, when the system works well. Retractions are part of that corrective process. Second, remember that bees can be found in lawn areas, particularly if lawns are less managed. The Lermann study demonstrated that lawns can host a surprising richness of bee species: 72, 60, and 62 bee species, in lawns mowed every week, two weeks, or three weeks, respectively. Note that to be part of this study, homeowners had to agree to not use herbicides or irrigation, during the length of the study. As a result of reduced management, lawns in this study often had bare patches that might be good nesting habitat for soil-nesting bees. Relaxing your mowing regime to every 1-2 weeks is supported by good science. Stowing your mower for an entire month is not. Finally, if you want to manage your yard for pollinators, planning and planting a pollinator garden is likely to net more species than stowing your mower. Indeed, many critics of the No Mow May movement, including native plant advocate Doug Tallamy, suggest that providing a temporary safe haven, regardless of its length of time, is counterproductive for pollinators and other wildlife it was meant to benefit. We currently have a paper in review, addressing this very topic. I look forward to sharing the highlights with readers, once it is published.

[1] Journal of Applied Ecology 57: 436-446

[2] Biological Conservation 221: 160-174

[3] PeerJ 8:e10021

[4] New York Times, March 28, 2022.

[5] Appleton Common Council resolution and vote, April 1, 2020.

[6] NBC 26 Local News, April 22, 2022.

[7] Post Crescent, April 10, 2023.