By Alyssa Premo

The Social Hierarchy

Lakshminarayanan/447e4f17ce6a424cf845bc14

b068072609faa825/figure/4

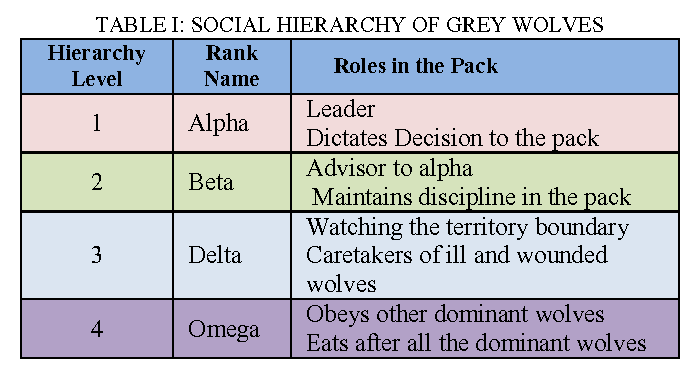

Perhaps one of the most incredible aspects about wolves surround their strong social bonds. Wolves typically live in familial groups of five to nine members. However, this unit is full of complex social hierarchies. The alphas are a breeding pair of wolves who mate for life and maintain order in the pack. The alpha female is typically the wolf who holds the pack together. Betas are the next highest in ranking, followed by the mid-ranking and omegas. There can be flow between the mid-ranking and omega social status, and “although an omega may hold that position for many years, it is not unheard of for the pack to pick a new omega and let the other retire” (Living with Wolves).

Communication

“Wolves communicate through body language, scent marking, barking, growling, and howling. Much of their communication is about reinforcing the social hierarchy of the pack. When a wolf wants to show that it is submissive to another wolf, it will crouch, whimper, tuck in its tail, lick the other wolf’s mouth, or roll over on its back. When a wolf wants to challenge another wolf, it will growl or lay its ears back on its head. A playful wolf dances and bows. Barking is used as a warning, and howling is for long-distance communication to pull a pack back together and to keep strangers away” (The National Wildlife Federation).

Notice the playful manor in which the two wolf brothers communicate to maintain their social bond in the video below.

The Bonds Between Pack Members

effectively communicate during hunts and coordinate hunts

as presented by national geographic.

Because wolves live in familial units, it facilitates a strong emotional bond between each member. These relationships are often maintained by play, even among the mature adults. This allows certain members to be assigned to special tasks such as coordinating hunts and guarding territory.

One of the most fascinating aspects of these special bonds is the raising of pups. Wolves are highly social animals, and the adults provide pups with the key knowledge to survive in the wilderness. According to Living With Wolves, “Wolves pass on what can be best described as culture. A family group can persevere for several generations, even decades, carrying knowledge and information through the years, from generation to generation”. The bond between each member is so strong that there is evidence the pack will mourn the loss of a member. If an alpha is lost, specifically the alpha female, the entire pack is at risk of disintegrating.

“When we look at wolves, we are looking at tribes—extended families, each with its own homeland, history, knowledge, and indeed, culture” (Living With Wolves).

The Lone Wolf

Most wolves go their entire lives within one pack, but others can go through a period of solitude, often referred to as the “lone wolf”. Both males and females can leave the pack, but predominantly young female wolves between the ages of one to four years old leave their pack in search of a pack of their own due to the constraints of only being one breeding pair in a pack. Wolves need companionship because of their social requirements and the need of other members of their species to hunt larger game, and therefore, the lone wolf would much prefer to be in a pack (Living With Wolves). However, wolves leaving their families helps to prevent inbreeding and increase the genetic diversity of the species. Furthermore, it is crucial for lone wolves to find a pack of their own to increase its likelihood of survival.

Works Cited:

Living with Wolves. “The Social Wolf.” Living with Wolves, Living with Wolves, 6 Mar. 2020, www.livingwithwolves.org/about-wolves/social-wolf/.

The National Wildlife Federation. “Gray Wolf.” National Wildlife Federation, National Wildlife Federation, n.d., www.nwf.org/en/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Mammals/Gray-Wolf.