Moving out of your parent’s house for the first time is not an easy thing to do. Especially if you move all the way across the country! But two weeks into my OSG Summer Scholars internship and I know I’m doing the right thing for myself. I’m excited to work live and in person with the animals and people that I’ve been working with for over a year. This summer I’m working on another piece of the 10+ year project trying to understand the relationship between a native burrowing mud shrimp, Upogebia pugettensis, and it’s invasive parasitic isopod, Orthione griffenis. Upogebia pugettensis populations up and down the west coast have drastically declined, with some local extinctions in California. Collapses in mud shrimp populations have been associated with infestations of Orthione and former pesticide use from oyster farmers.

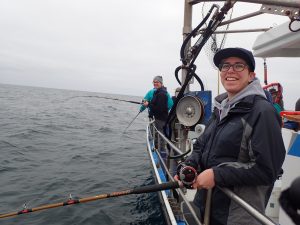

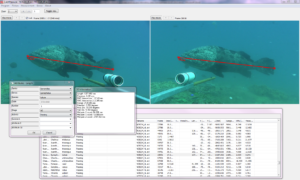

After taking a week to drive from North Georgia to the Oregon coast, I jumped right into my work duties. My lab partner, Joshua (an Oregon State REU intern), and I get the privilege of doing field and lab work this summer. Some of our field work includes trudging out onto the mudflats behind Hatfield Marine Science Center at low tides. On the mudflat, we take cores and sieve them down to collect the mud shrimp. We also get to bike out onto the fishing pier next to the Yaquina Bay Bridge after dark during high tides. On the pier, we are doing plankton tows, which are conical fine-mesh nets with a cod end that traps critters that are riding the incoming tides into the bay. Back in the lab, we sort and analyze the mud shrimp and the plankton tows. The mud shrimp are analyzed based on aspects like species, sex, carapace length, infested with Orthione, size of Orthione, and other important factors. The plankton tows get analyzed for juvenile mud shrimp (both Upogebia and Neotrypea) and Orthione cryptoniscans (one of the larval stages of Orthione).

Through this project we are hoping to determine the life span and the settlement schedule of the cryptoniscans and to get large enough samples of mud shrimp to overcome sampling bias to ground truth the age/size relationship. Ultimately, accomplishing this project is putting another piece of the puzzle down into saving this mud shrimp from extinction. To do that, we need to know the relationship between the shrimp and the parasite better. That’s where my team and I come into play. With our work we can try and answer questions like: When do the shrimp become infested? Do the cryptoniscans settle on the shrimp or on other Orthione? Do cryptoniscans wait for a certain time to settle? What are they waiting for? Some kind of signal from the shrimp? Learning these answers will be one step closer to answering the big picture question “how can we turn this around or CAN we turn this around?”

Mud shrimp are native ecosystem engineers. They build permanent y-shaped burrows in the sediment that influence the estuarine benthic community by providing habitat and enhancing nutrient cycling. By saving these shrimp we are helping to advance OSG’s vision and mission to have thriving coastal communities & ecosystems. This research would also help to balance the forces of ecology and economy to inform oyster growers how to safely manage the burrowing mud shrimp populations without depleting them.