During spring term Dr. Kara Ritzheimer’s History 310 (Historian’s Craft) students researched and wrote blog posts about OSU during WWII. The sources they consulted are listed at the end of each post. Students wrote on a variety of topics and we hope you appreciate their contributions as much as the staff at SCARC does!

This post was written by Caitlin Patton.

In November 1942, the Oregon State Barometer published an article titled “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure,” which provides insight into the dietician and nutrition programs in Oregon State College’s (OSC) School of Home Economics.[i] Further research reveals that other departments beyond Home Economics developed programs to reach the broader Corvallis and Oregon communities. These programs reflect an increase in support from doctors and the general public for nutrition research and its practical applications during the beginning of World War II. The American government worked with universities across the country, including OSC, to develop and manage numerous programs to share information on and provide support for the nutrition of both civilians and soldiers.

This November 1942 article in the Oregon State Barometer, OSC’s student-run newspaper, reported the U.S. Army had requested “1200 additional trained dieticians” and that Dean Ava B. Milam, “who heads the [home economics] school on this campus and who is the chairman of the state committee on nutrition for defense,” shared this information at a recent Faculty Triad club luncheon. The article also described new collaborative programs between the military and the school to certify graduates as dieticians faster using apprenticeship programs. It also explained that Dean Milam hoped to apply the apprenticeship model to other subjects.[ii] This article shows how the army was attempting to recruit dieticians, but it does not explain if the army was asking for recruits directly from the home economics school at OSC or from colleges in general.[iii] Additionally, some quotes from Dean Milam imply that the increased recruitment of dieticians was the result of a shift in public opinion towards concern about diet for civilian workers as well as soldiers.[iv] This article raises many questions about the forces and factors which influenced the development of the dietician program at Oregon State College.

Primary sources demonstrate the collaborative efforts of the dieticians and nutritionists within OSC’s Home Economics Department and the American government during World War II to improve the nutrition of both soldiers and civilians. Wartime articles sharing the experiences of recent OSC graduates showcased the work these dieticians were doing to help soldiers. For example, two articles from the Barometer, both printed in 1944, list several OSC graduates from the home economics department who were working as dieticians for the army.[v] Additionally, the Oregon State Yank, a magazine for OSC alumni serving in the armed forces, published articles that recounted the experiences of graduates serving as dieticians in various military theaters. One of these articles, titled “SHE-I Observations,” named various alumni working as dieticians at Fort Lewis and McChord Field, both in Washington. One OSC-trained dietician was even working with troops stationed in England.[vi] Another article titled “The Feminine Front” introduced readers to Roberta “Becky” Beer, a recent alum who had “answered the urgent call for dieticians.”[vii]

Home Economics also worked with government organizations to change the nutrition habits of civilians. In 1943, Dean Milam served as chairman of the Oregon Nutrition Committee for Defense. In this position, she took an active role in organizing numerous policies and programs meant to provide nutritional information and support to American families.[viii] As the Dean of the Home Economics School, Milam may have also been responsible for adding the class “Nutrition for National Defense” in the 1942-1943 class catalog.[ix] A survey of prior catalogs reveals this was a new class. Although details about course content are unavailable, it’s likely that Milam and others hoped that this new course would communicate useful information to women who might one day serve in the army or whose work might support their local communities.[x] Mabel C. Mack, an OSC graduate from the School of Home Economics also published several pamphlets with the Oregon State College Extension Service on food supply, nutrition, and management during wartime for families.[xi] Mack had completed a PhD at OSC in 1939 and may have served on Milam’s Oregon Nutrition Committee for Defense.[xii] These documents show how the women of the School of Home Economics contributed to the national conversation about the nutritional well-being of soldiers and civilian families.

The first page of Mabel C. Mack’s “Food to Keep You Fit,” adorned with patriotic decorations, provides information about the author and publisher. The second page of “Food to Keep You Fit” lists daily amounts for different food categories and pictures of those categories. The third page of “Food to Keep You Fit” provides readers with a recommended pattern of food categories for breakfast, dinner, and supper or lunch. The fourth and final page of “Food to Keep You Fit, lists weekly amounts of different food categories as well as an image of a red shield with the text “Defend Your Health With Protective Foods.” Available in Special Collections & Archives Research Center, hereafter referred to as SCARC, Oregon State University Libraries, Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1941), Extension Bulletin 562.

OSC’s School of Agriculture and Extension Services also played a key role in wartime food and nutrition programs. Perhaps taking a page from the School of Home Economics, faculty authored pamphlets focused on food management during the war. For example, in 1943 A. G. B. Bouquet, Professor of Vegetable Crops, printed a pamphlet on growing a vegetable garden.[xiii] The next year, Thomas Onsdorff, an Associate Professor of Food Industries, and Lucy A. Case, a nutritionist from Extension Services, together published a guide on canning vegetables, fruits, meats, fish, and more. It also listed other resources published by OSC and the U.S. Department of Agriculture that families could easily request from their County Extension Office or OSC’s Home Economics Extension Service if they wanted more information.[xiv]

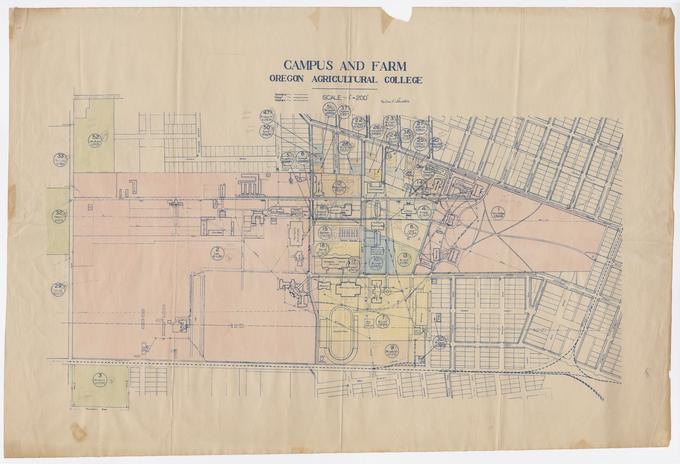

OSC and Extension Services also supported the Victory Garden Program. W. A. Schoenfeld, Dean and Director of Agriculture, presided over a conference, held in the Memorial Building on December 4th, 1942, for representatives of local branches of the Victory Garden Program in Oregon. Some of the featured guests included economists and horticulturists from Extension Services as well as state officials.[xv] And in an effort to share their expertise with the community, OSC faculty reached out to local schools. Professor Bouquet (noted above) developed a popular victory garden class for high school students.[xvi] The class included a lecture that guided students on which crops would be best to grow for canning and on how to maximize the amount of produce grown in their gardens.[xvii]

The various nutrition programs that OSC faculty developed and managed reflect a broader effort during WWII to improve nutrition for both soldiers and civilians. As the army began to draft soldiers, it also conducted surveys on the health of recruits and found that 25% of conscripts displayed symptoms of prior or recent malnutrition.[xviii] In 1940, President Roosevelt called for a National Nutrition Conference for Defense on the grounds that “Fighting men of our armed forces, workers in industry, the families of these workers, every man and woman in America, must have nourishing food. If people are undernourished they cannot be efficient in producing what we need in our unified drive for dynamic strength.”[xix] The first Nutrition Conference for Defense, held in 1941, stressed the importance of addressing national nutrition through programs across different levels of government, from the national down to the local.[xx] Although the Victory Garden Program was managed at the local level, it had a great national impact: families across the country locally grew 8 million total tons of food in a single year.[xxi] The national and state governments also developed programs such as free school lunches and food stamps to support struggling families.[xxii] The U.S. Congress passed the Tydings Amendment in 1942, which granted farm workers an exemption from the draft so that they could continue to produce necessary foods throughout the war.[xxiii] The U.S. Army, meanwhile, designed the dietician apprenticeship program mentioned in the 1942 Barometer article to secure nutrition support for both military and civilian hospitals.[xxiv] University students who completed an approved course could apply to serve as an apprentice at a military or civilian hospital for six months before serving another six months at another U.S. Army hospital. The army also developed another program to recruit dieticians from unrelated undergraduate programs.[xxv] These national nutrition programs benefited both civilians and the military greatly.

The November 1942 Barometer article “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure” reveals the important role that Oregon State College faculty and alumni played in wartime efforts to promote nutrition across the United States and in the military. The graduates of the home economics school worked with soldiers as dieticians and shared resources with civilian families. The other departments of OSC also reached out to the Oregon community with guides and education programs. The nutrition programs of Oregon State College, from the dietician apprenticeship program to the Victory Gardens Program, contributed to the national efforts to improve the nutrition of Americans at home and soldiers abroad.

[i] “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure,” Oregon State Barometer, November 20, 1942: 1.

[ii] “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure,” 1.

[iii] “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure,” 1.

[iv] “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure,” 1.

[v] “Armed Services Claim Co-eds,” Oregon State Barometer, May 19, 1944: 3, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nk56z; “YANKEE DOODLE DANDIES…,” Oregon State Barometer, March 7, 1944: 1, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nk402.

[vi] “SHE-I Observations,” Oregon State Yank, November 1944:14, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719t25j.

[vii] Jayne Walters Latvala, “THE FEMININE FRONT,” Oregon State Yank, November 1944: 14, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719t25j.

[viii] “Minutes of Meeting, Oregon Nutrition Committee for Defense,” June 25, 1943, https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/ww2/Documents/services-nut3.pdf.

[ix] “Foods and Nutrition,” in Oregon State College CATALOG 1941-42 (Eugene: Oregon State Board of Higher Education, 1941), 342-345.

[x] “Foods and Nutrition,” in Oregon State College CATALOG 1942-43 (Eugene: Oregon State Board of Higher Education, 1942), 343.

[xi] Mabel C. Mack, “FOOD To Keep You Fit,” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650 (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1941), Extension Bulletin 562; Mabel C. Mack, “Use Milk, Eggs, and Milk Products,” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650 (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1941), Extension Bulletin 583; Mabel C. Mack, “Planning YOUR FAMILY”S FOOD SUPPLY,” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1942), Extension Bulletin 588; Mabel C. Mack, “Planning YOUR FAMILY”S FOOD SUPPLY,” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650 (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1943), Extension Bulletin 616.

[xii] Mabel Clair Townes Mack, “A Study of the Kitchen Sink Center In Relation to Home Management,” (PhD diss., Oregon State College, 1939), 1; “Minutes of Meeting,” 1.

[xiii] A. G. B. Bouquet, “Farm and Home VEGETABLE GARDEN,” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650 (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1943), Extension Bulletin 614.

[xiv] Lucy A. Case and Thomas Onsdorff, “Home Food Preservation by Canning * Salting,” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650 (Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1944), Extension Bulletin 642.

[xv] “Victory Garden Heads To Convene at OSC,” Oregon State Barometer, November 25, 1942: 1, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj11d.

[xvi] “Oregonian Features Bouquet in Editorials,” Oregon State Barometer, March 3, 1943: 1, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj59k.

[xvii] “Victory Gardeners Hear Crop Lecture,” Oregon State Barometer, March 2, 1943: 2, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj589.

[xviii] Karen Stein, “History Snapshot: Dietetics Student Experience in the 1940s,” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 114, no. 10 (September 22, 2014): 1648–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.001, 1652.

[xix] “The National Nutrition Conference,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 56, no. 24 (1941): 1234, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4583763.

[xx] “The National Nutrition Conference,” 1248-1249.

[xxi] H. W. Hochbaum, “Victory Gardens in 1944: How Teachers May Help,” The American Biology Teacher 6, no. 5 (1944): 101–3. https://doi.org/10.2307/4437480, 101.

[xxii] “The National Nutrition Conference,” 1248-1249; “Minutes of Meeting,” 1.

[xxiii] Lizzie Collingham, The Taste of War (New York, NY: Penguin Group USA, 2012), 75–88, 78-79.

[xxiv] “Home Ec Schools Under Pressure,” 1.

[xxv] Stein, “History Snapshot: Dietetics,” 1650-1651.

Bibliography:

“Armed Services Claim Co-eds.” Oregon State Barometer, May 19, 1944: 3. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nk56z.

Bouquet A. G. B. “Farm and Home VEGETABLE GARDEN.” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, Extension Bulletin 614. Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1943.

Case, Lucy A. and Thomas Onsdorff. “Home Food Preservation by Canning * Salting.” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, Extension Bulletin 642. Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1944.

Collingham, Lizzie. The Taste of War, 75–88. New York, NY: Penguin Group USA, 2012.

“Foods and Nutrition.” In Oregon State College CATALOG 1941-42, 342-345. Eugene: Oregon State Board of Higher Education, 1941.

“Foods and Nutrition.” In Oregon State College CATALOG 1942-43, 343-345. Eugene: Oregon State Board of Higher Education, 1942.

Hochbaum, H. W., “Victory Gardens in 1944: How Teachers May Help.” The American Biology Teacher 6, no. 5 (1944): 101–3. https://doi.org/10.2307/4437480.

“Home Ec Schools Under Pressure.” Oregon State Barometer. November 20, 1942: 1.

Latvala, Jayne Walters. “THE FEMININE FRONT.” Oregon State Yank, November 1944: 14. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719t25j.

Mack, Mabel C. “FOOD To Keep You Fit.” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, Extension Bulletin 562. Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1941.

Mack, Mabel C. “Use Milk, Eggs, and Milk Products.” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, Extension Bulletin 583. Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1941.

Mack, Mabel C. “Planning YOUR FAMILY’S FOOD SUPPLY.” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, Extension Bulletin 588. Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1942.

Mack, Mabel C. “Planning YOUR FAMILY’S FOOD SUPPLY.” in Oregon State College Extension Service Bulletin 551-650, Extension Bulletin 616. Corvallis: Oregon State System of Higher Education, 1943.

Mack, Mabel Clair Townes. “A Study of the Kitchen Sink Center In Relation to Home Management.” PhD diss., Oregon State College, 1939.

“Minutes of Meeting, Oregon Nutrition Committee for Defense.” June 25, 1943. https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/ww2/Documents/services-nut3.pdf.

“Oregonian Features Bouquet in Editorials.” Oregon State Barometer, March 3, 1943, 1. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj59k.

Peterson, Anne, “Dietitians Seek Military Status In Army Service.” The New York Times, October 13, 1940. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1940/10/13/94840663.html?pageNumber=60.

“SHE-I Observations.” Oregon State Yank, November 1944: 14. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719t25j.

Stein, Karen.“History Snapshot: Dietetics Student Experience in the 1940s.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 114, no. 10 (September 22, 2014): 1648–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.001.

“The National Nutrition Conference.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 56, no. 24 (1941): 1233–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4583763.

“Victory Garden Heads To Convene at OSC.” Oregon State Barometer, November 25, 1942: 1. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj11d.

“Victory Gardeners Hear Crop Lecture.” Oregon State Barometer, March 2, 1943: 2. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj589.

“YANKEE DOODLE DANDIES…” Oregon State Barometer, March 7, 1944: 1. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nk402.