During winter term 2025 Dr. Kara Ritzheimer’s History 310 (Historian’s Craft) students researched and wrote blog posts about OSU during WWII. The sources they consulted are listed at the end of each post. Students wrote on a variety of topics and we hope you appreciate their contributions as much as the staff at SCARC does!

Blog post written by Ian Busby

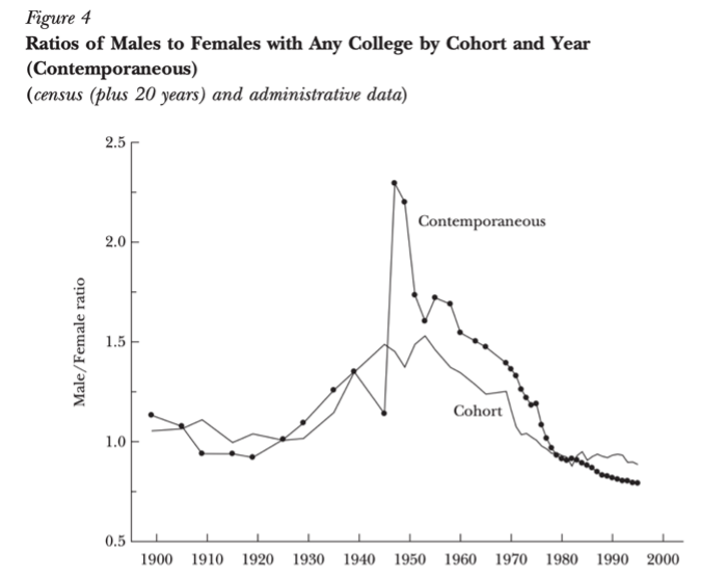

The demands of the United States’ war effort broadly reduced male college enrollment during WWII. Science and engineering were both part of a push and pull between a need for soldiers and a need for technically trained individuals for other aspects of the war effort. Due to the School of Science structure, changes in curriculum, and losses in faculty, the war led to increasingly freshman and sophomore dominated sciences at Oregon State College (OSC). General catalogs provide key information on both enrollment and courses at OSC, and are a critical resource when investigating trends in enrollment.

The summary of enrollment and degrees in the 1943-44 Oregon State College General Catalogue helps describe student focuses going into the height of wartime. The Oregon State Board of Higher Education published the catalogue in August 1943 to inform incoming and on-going students of the available degrees and courses. Of particular interest are pages 378 and 379, which detail the demographics and numbers for enrollment in the previous academic year of 1942-43. In the catalogue, OSC splits curriculum primarily between professional schools and liberal arts and sciences. Upper division coursework in the school of science is divided into the subjects of General Science, Bacteriology, Botany, Chemistry, Entomology, Geology, Mathematics, Physics, Zoology, nursing education, and science education, the last two not explicitly shown in Figure 1.[i] This catalogue is neatly typeset, and is clearly mass-produced. At nearly four hundred pages, the catalogue is quite large. It appears to be in good condition, and presumably due to its mass-produced nature a number are still in existence. In 1942-43, there was a total enrollment of 709 Lower division students in the Liberal Arts and Sciences and only 91 total students in the upper division.[ii] That said, only 421 students are enrolled in lower division science courses. This means that the ratio of upper division to lower division science students is less than one to four, in other words for every four lower division students there is less than one upper division student.

It is first necessary to understand what the Lower Division was in order to contextualize its enrollment information. Established in 1932, the Lower Division and School of Science are recent additions to Oregon State College (OSC) as of the early 1940s.[iii] Particularly, OSC President Francois Gilfillan in his 1941-42 Biennial report stated the goal of the Lower Division was to provide two years of generalized education, after which students focused on science would continue at OSC and those focused on the liberal arts would attend the University of Oregon.[iv] The Lower Division was specifically connected with science; all students studying liberal arts or science would have spent their first two years in the Lower Division. This is confirmed in a 1944 advertisement for the college where OSC describes the Lower Division as a balanced set of classes for those studying liberal arts and sciences, with opportunities for students to test several different fields.[v] It seems that students of science would not choose a particular major until after completing two years of Lower Division study. This may seem like the current “Bacc core” system, however, this was isolated to the School of Science. For example, in the 1943-44 Catalog, a bachelor’s in Agriculture required freshman to take zoology, botany, astronomy, chemistry and English composition all from the Schools of Science and Liberal Arts.[vi] Most engineers on the other hand only have to take English composition and possibly general chemistry.[vii] At this point, aside from two years of required military instruction for all male students under age 26 and possibly English composition, there is appears to be no college wide general requirements like the modern “Bacc core” system. [viii]

The bottom-heavy enrollment in 1942-43 raises two questions. First, was the bottom-heavy enrollment a one-time occurrence, or did OSC consistently exhibit this sort of enrollment during WWII? Second, if OSC did consistently show bottom-heavy enrollment, why were so many more students enrolling in lower-level science courses?

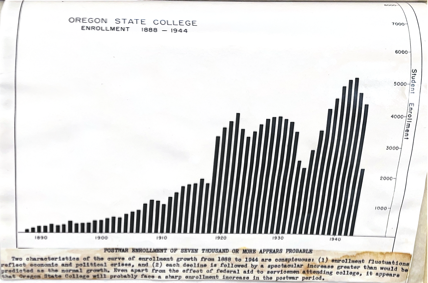

To answer the first question, this bottom-heavy enrollment indeed continues into the 1943-44 academic year. Enrollment data shows only 49 students combined across the various science majors and a comparably huge 303 students in the Lower Division sciences.[ix] Comparing enrollment to the other six schools, Agriculture, Education, Engineering, Forestry, Home Economics, and Pharmacy, reveals that even prior to the war the School of Science was bottom heavy with about two upper-level students to every five lower-level students.[x] The School of Science as well as Engineering both saw steady increases in enrollment until the 1943-44 and 1944-45 academic years, where there were large dips in enrollment across the board except in Home Economics, Pharmacy, and Education.[xi] While not shown in Figure 3, near the end of the war, OSC appears to have removed Secretarial Science from the Professional Curricula and instead there was a new Division of Business and Industry.[xii] Post war, most schools saw both an increase in total enrollment and in the ratio of upper level to lower-level students, while Education and Home Economics remained mostly steady in both metrics throughout the entire date range.[xiii] This is likely due to the higher female enrollment in these fields, particularly in Home Economics. Full graphs of total enrollment, ratio of upper to lower-level enrollment, and enrollment by class can all be seen in detail by year in Figure 3. Broadly speaking, the School of Science had the most bottom-heavy enrollment of all the schools for a vast majority of the eleven-year span considered.

To answer the second question, the uniquely bottom-heavy enrollment in the School of Science was likely caused by a combination of the Lower Division Structure and war related changes. As already mentioned, the Lower Division was meant for a general education, so it is natural to expect a high enrollment compared to the upper-level majors. Students focusing on liberal arts likely would have still taken science courses boosting lower-level science enrollment. Other likely causes of this bottom-heaviness include open defense jobs which may have drawn students from completing their studies and moving on to the upper division. The February 23, 1943 edition of the Oregon State Barometer includes a call to students with at least two years of electrical engineering or physics to work as radio interception operators without completing their degrees.[xiv] Jobs like this may have been quite a draw for students wanting to contribute to the war effort. The Lower Division also contained classes aimed at war time training. The proposed course changes for the 1944-45 academic year include a dropped Z215, “Practical Physiology for the Wartime Needs,” initially introduced to meet early war needs.[xv] Such wartime classes likely created larger draws for students to enroll, even those not majoring in science. A lack of professors may also have affected upper division teaching. At least ten School of Science professors are listed as in war service, with several noted as needing replacements or departmental adjustments.[xvi] This sentiment is echoed in the 1941-1942 Biennial Report where Gilfillan plainly states that as of 1942, thirteen School of Science staff had joined the war, and that “Their replacement presents a serious problem.”[xvii] While a lack of staff could affect both lower and upper level courses, the upper levels would have been more technical and required more qualified staff. It is natural then to assume that this lack of faculty impacted upper-level enrollment disproportionately. Additionally, OSC may have shifted existing staff more towards the Lower Division where the higher enrollment meant higher demand, further contributing to the bottom-heaviness.

Throughout the war, most of the different Schools at OSC experienced only moderate increases or decreases in enrollment until the 1943-44 academic year, where enrollment dropped drastically, followed by a sharp rise after the war. OSC was not unique in these aspects. V.R. Cardozier discusses enrollment of state universities in the book Colleges and Universities in World War II, and specifically describes how Indiana University saw modest declines until 1943, when enrollment boomed due to army and navy programs.[xviii] Indiana University’s enrollment trend matches much of what was seen at OSC, though OSC saw its enrollment in Science and Engineering rise before 1943 and drop sharply afterward. In a national sense, state universities appear to have hemorrhaged students the least during WWII due to, as Cardozier puts it, “the variety of training programs they could offer.”[xix] That said, state universities often still saw large declines, with Berkeley’s and UCLA’s pre-war enrollment being reduced by more than half by the 1944-45 academic year. OSC wasn’t entirely immune either, and although there was growth especially in the School of Engineering early in the war, OSC’s enrollment decreased drastically in 1943-44 and 1944-45. This early growth very well could have been influenced by the Army Specialized Training Unit (ASTP), with ASTP making up 381 of 3078 total male enrolled students in 1942-43 and 1614 of 2159 total enrolled male students in 1943-44.[xx] While discussing the impact of WWII on California community colleges, Edward Gallagher describes the concerted effort for national defense, particularly how in California junior colleges “Courses were structured to meet war needs and their content emphasized military use.”[xxi] The 1944 Serviceman’s Readjustment Act (henceforth G.I. bill) provided returning veterans free access to higher education, among other benefits. After the war, students at California community college largely enrolled in lower-level courses mirroring courses at universities, and most of the veteran students “planned to transfer to four-year institutions.”[xxii] Lower-level classes once again emphasized preparation for upper-level coursework; in the case of the California community colleges this meant a transfer to universities and at OSC this meant moving on to specific School of Science majors or transferring to the University of Oregon for the humanities. Enrollment at OSC ballooned in the post WWII era, and this was mirrored nationally, with an increase from 1.5 million students pre-war to 2.3 million by 1947.[xxiii] Ryan Skinnell argues that lower-level courses, particularly first-year composition, were instrumental. Writing skills allowed students, many of whom were returning G.I.s, to complete either two or four years and remain employable and acted as a selling point “come to college, learn to read and write so you can rejoin the workforce with state of the art, practical skills for the modern economy.”[xxiv] This mirrors OSC’s Lower Division marketing that students could learn broad technical skills, with a 1944 advertisement stating “liberal education is combined with practical education in every professional school at Oregon State.”[xxv] Altogether, the enrollment trends and course structure at OSC during and after WWII diverge little from institutions across the country.

The OSC School of Science show freshman and sophomore dominated enrollment over a period from before to after WWII spanning eleven years. This bottom-heaviness is most prevalent at the height of the war, likely due to changes in curriculum for the war effort, a loss of faculty, and the structure of the Lower Division. Most of the other OSC schools demonstrated similar bottom-heaviness during the war, albeit typically to a less degree. Discussions from the OSC president, faculty war leave reports, and administrative council meeting minutes have all expanded these enrollment trends in science beyond just the numbers. OSC is broadly like the enrollment trends at other state institutions, but using specific enrollment data has revealed additional trends in enrollment lost when looking at just overall institution numbers. Not every School at OSC demonstrated the same behavior, and each was affected by the war in unique ways.

[i] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1943-44,” August 1943, Oregon Digital, Special Collections and Archives Research Center (Hereafter SCARC), Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, 3, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v93w.

[ii] “College Catalog, 1943-44,” 378.

[iii] Francois A. Gilfillan, “Biennial Report of Oregon State College, 1941-42,” 1942, 32,37, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx71d395d.

[iv] Francois A. Gilfillan, “Biennial Report,” 32.

[v] “This is Oregon State, 1944,” 1944, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx71cs65n, 14.

[vi] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1943-44,” 175.

[vii] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1943-44,” 264-268.

[viii] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1943-44,” 67-68, 339.

[ix] “Oregon State College Students Enrolled, 1943-1944,” May 1944, Oregon Digital, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/qf85nc515, 45.

[x] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1937-38,” April 1937, 457, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon Digital, https:/oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v350; “Oregon State College Catalog”, 1938-39,” April 1938, 477, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v86g; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1939-40,” August 1939, 490, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v899; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1940-41,” July 1940, 497, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v902; “Oregon State College Degrees Conferred and Students Enrolled 1940-41,” July 1941, 70, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/1g05fc83z.

[xi] “Oregon State College Degrees Conferred and Students Enrolled 1941-42,” October 1942, 69, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/0z708x48s; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1943-44,” August 1943, 378, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v93w; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1945-46,” June 1945, 409, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v87r; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1946-47,” April 1946, 405, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v856.

[xii] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1945-46,” 407.

[xiii] “Oregon State College Catalog, 1947-48,” March 1947, 414, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v84x; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1948-49,” March 1948, 424, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v82c; “Oregon State College Catalog, 1949-50,” 1949, 453, SCARC, Historical Publications of Oregon State University, Oregon State University General Catalogs, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/fx719v813.

[xiv] Pat Glenn, “Scouting the Campuses,” February 23, 1943, Oregon State Barometer, Oregon Digital, https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/8k71nj53x.

[xv] “Proposed Course Changes for 1944-45,” December 15, 1943, SCARC, Admin Council Records, Meeting minutes, Box-folder 2.4, 114.

[xvi] “Full Time Staff in War Service,” October 8, 1942, SCARC, Oregon State College History of World War II Project Records, 1940-1947, List of Staff Granted Leaves, 1940-46, 4.

[xvii] Francois A. Gilfillan, “Biennial Report,” 37.

[xviii] V. R. Cardozier, Colleges and Universities in World War II (Praeger, 1993), 116.

[xix] Cardozier, Colleges, 115-116.

[xx] “Oregon State Catalog, 1943-44,” 378;“Oregon State Catalog 1945-46,” 409.

[xxi] Edward A. Gallagher, “Short-term military needs or long-term curricular reform? The impact of World War II on California Community Colleges,” Michigan Academician 36, no. 3 (2004): 302.

[xxii] Gallagher, “Short-term military,” 306.

[xxiii] Ryan Skinnell, “Enlisting Composition: How First-Year Composition Helped Reorient Higher Education in the GI Bill Era,” Journal of Veterans Studies 2, no. 1 (2017), 79.

[xxiv] Skinnell, “Enlisting Composition,” 81.

[xxv] “This is Oregon State, 1944,” 14.