Trade Journal Articles

Oregon nurseries light the way for houseplants

By: Lloyd Nackley / Digger January 2026

With trees, size matters

By: Lloyd Nackley / Digger January 2026

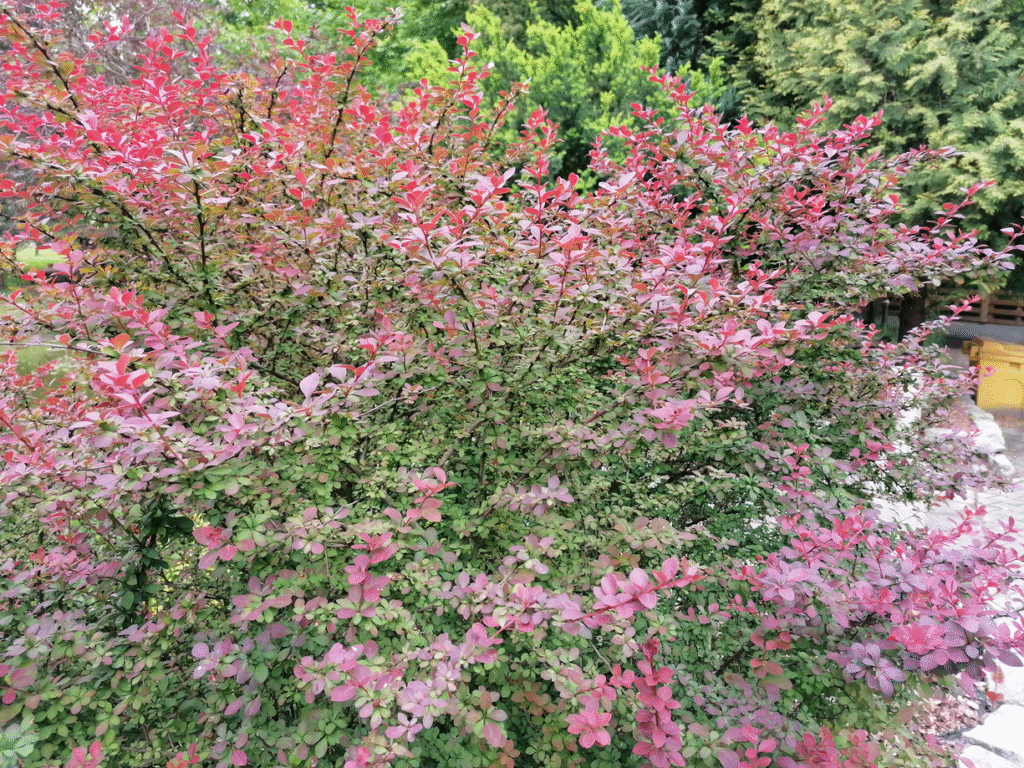

Red, Pink, and Burgundy Hues Drive Tropical Plant Demand

By: Emily Hoard / Digger January 2026

Olive trees may be perfect for arid Oregon summers

By: Mike Darcy / Digger January 2026

Canopii’s Automated Greenhouse Shows Promise for Growers

By: Jon Bell / Digger January 2026

Automation Improves Greenhouse Quality and Efficiency

By: Jon Bell / Digger January 2026

Scientific Journal Articles

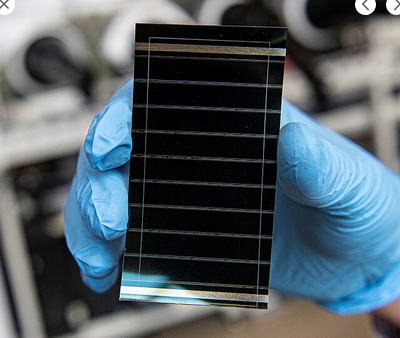

Photosynthetic Performance of Perovskite Solar Cells in Greenhouses

By: Parker Egan Persons, Marc W. van Iersel, Susanne Ullrich, Jie Zhan, Tu Anh Ngo, Tho Duc Nguyen, Paul M. Severns, Rhuanito Soranz Ferrarezi

HortSci: Volume 151: Issue 21

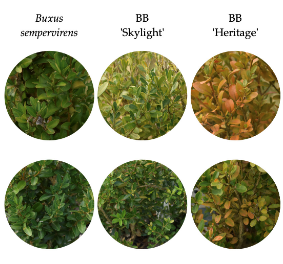

Connecticut Nursery Industry Views on Invasive Plant Sales

By: Lauren E. Kurtz, Alyssa J. Siegel-Miles, Mark H. Brand, Victoria H. Wallace

HortTech: Volume 36: Issue 1

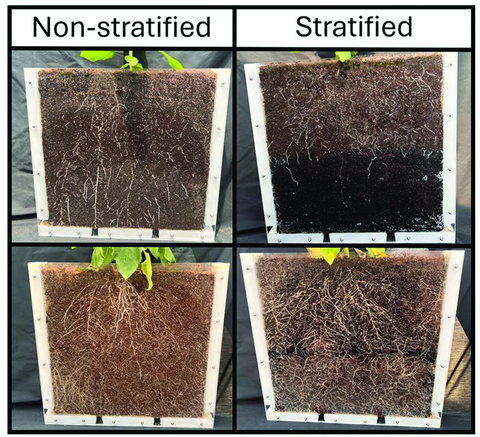

Hazelnut Shell Mulch Improves Container Nursery Production

By: Carter Miller, Herika Paula Pessoa, Seth Wannemuehler, Brandon Miller

HortTech: Volume 36: Issue 1

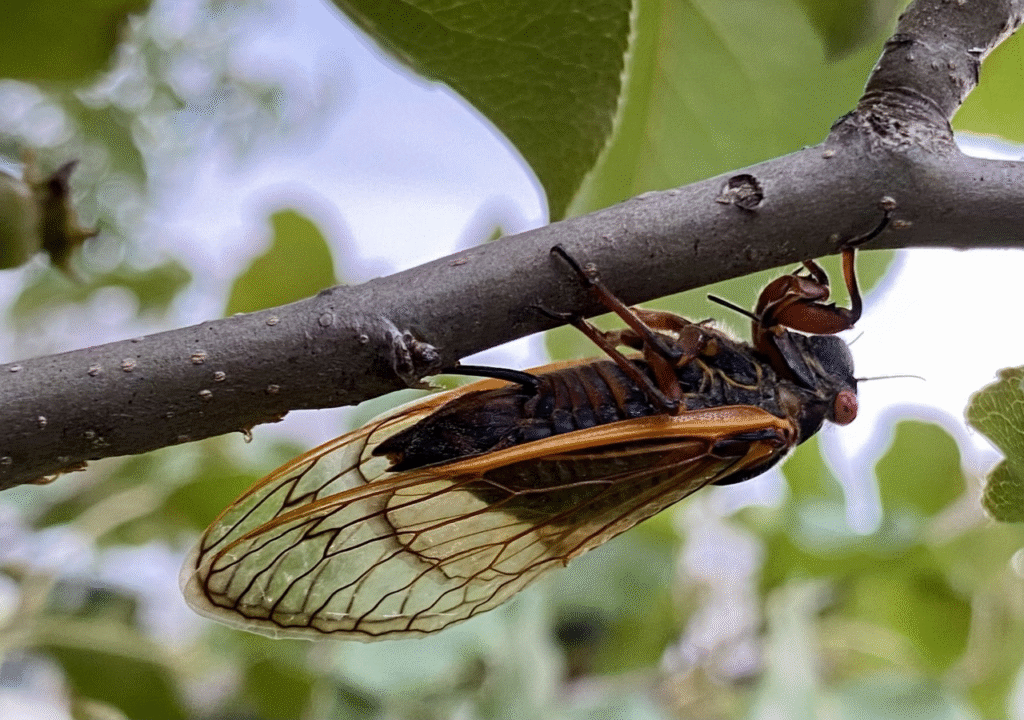

Oviposition Preferences of Periodical Cicadas in Nursery Trees

By: Martine Bowombe-Toko, Jason B. Oliver, Michael R. Allen, Douglas L. Airhart

JEH: Volume 40: Issue 4