As the #1 forestry college in the nation, the Oregon State University College of Forestry is a recognized leader in sustainable forestry, land management solutions, climate-friendly forest products, green building, and smart recreation and urban planning. We provide students with exceptional learning, research and development opportunities and are committed to building an inclusive culture at the College that identifies and removes barriers to learning and access. We prepare students to be agents of change, ready to create and contribute equitable solutions to present and future challenges concerning sustainability and global change.

Our transformational, collaborative research is carried out by faculty, staff and students and happens in classrooms, labs, on public and private lands across the state, including the H.J. Andrews Long Term Ecological Research Forest, in the College’s own 15,000 acres of Research Forests and in our 11 research cooperatives.

The College of Forestry received over $25 million in research grants and contracts for FY 2023. The awards support College of Forestry research that advances scientific knowledge critical to the health of forests, people and communities.

Here are some examples of the new awards:

The Economic Development Administration awarded $8 million for three projects titled:

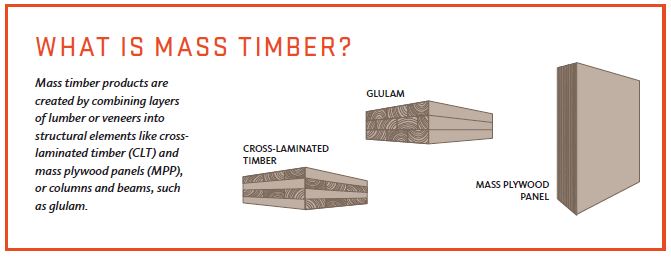

“Smart Forestry: Paving the Way from Forest Restoration to Mass Timber”

“Prototyping and Testing of Mass Timber Housing Systems” and

Construction of an “Oregon Fire Testing Facility”.

Business Oregon provided $1.9 million in matching funds for the project. Principal Investigators: Iain Macdonald and Woodam Chung

“Protecting water security from wildfire threats in the Western US”

Sponsor: US Forest Service for $1.6 million

Principal Investigator: Kevin Bladon

The USDI Bureau of Land Management awarded over $1.5 million for two projects titled:

“BLM Pacific Northwest Tribal Conservation Corps Project for Seeds of Success”

“The Fort Belknap Indian Community Seeds of Success Native Seed and Grassland Restoration Project”

Principal Investigator: Cristina Eisenberg

“Optimal individual tree management for climate smart forestry using process-based modeling”

Sponsor: USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture for $650K

Principal Investigator: Bogdan Strimbu

“Developing a Professional Fire Management Education, Training, and Experiential Learning Program”

Sponsor: USDI Bureau of Land Management for $800K

Principal Investigator: John Punches

“Forest Operations Training Partnership (LARI 202)”

Sponsor: US Forest Service for $267K

Principal Investigator: Francisca Belart