It’s not easy to find a marbled murrelet’s nest in Oregon. It wasn’t until 1990 that researchers even located the first one in the state. The elusive breeding behavior of this threatened species has made it challenging to protect through conservation efforts and strategic management of coastal forests. It’s clear the population of this small seabird has declined from historic levels — but the reasons why are murky.

That’s why a team of College of Forestry researchers launched Oregon’s first large-scale, long-term study of murrelet breeding biology. This collaborative project, initiated in 2016, drew immediate support from a diverse group of stakeholders across the state.

“Murrelets are a listed species, so there’s a lot of interest in recovering this population,” said Jim Rivers, an assistant professor of wildlife ecology who’s leading the research effort. “But we haven’t had the information we need to understand what’s constraining reproductive output.”

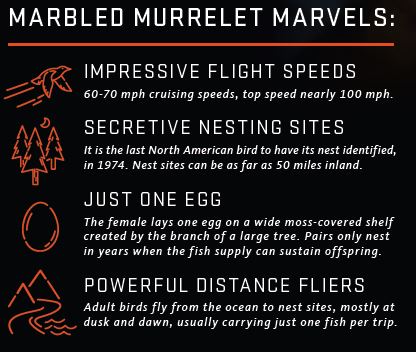

For phase one of the project, the research team turned to existing data to better understand why the birds travel inland to nest some years, but not others. Murrelets rely on the sea for their food, including forage fish like anchovy, herring, and smelt, and commute as much as 50 miles inland to nest in old-growth and late-successional forests, where they lay a single egg. The researchers learned when it’s a bad sea year and ocean temperatures are too high, the birds forego breeding, unable to get food to feed their young.

For the next phase of research, the team studied the murrelet’s breeding behavior, tracking them from sea to nest. Venturing out on a research vessel, the team boarded inflatable boats to catch murrelets, install radio tags and release the birds back into the wild. When breeding season hit, the team patrolled the coast with airplanes, listening for beeps from radio tags to narrow down potential nesting sites for the

ground crew and tree climber to locate.

But because murrelets nest in older forests, just getting to the vicinity of a nesting tree usually involves scaling piles of blowdown and bushwhacking through thick growth for miles. And murrelets are sneaky nest-builders — and sitters. They don’t use twigs and branches to build their nests like other birds. Instead, they find a mossy branch where they lay a single egg and take turns incubating it. They trade spots once every 24 hours, sitting so still that their only movement may be just the blink of an eye.

And when they’re moving in and out of the nest, they’re really moving. Murrelets have been clocked at nearly 100 mph and their typical cruising speed is 60-70 mph. They usually fly at dawn and dusk, so it takes an eagle eye to spot these birds and find their nests, a large reason there were only 29 active nests recorded in Oregon before this project. The team of OSU researchers more than doubled that number, also installing cameras at each nest to monitor success.

“We’re learning a lot about where murrelets are nesting, how successful they are and what causes them to fail,” said Rivers. “This information has been a long time coming, and it ties back to how challenging it is to do this fieldwork.”

A version of this story appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of Focus on Forestry, the alumni magazine of the Oregon State University College of Forestry.