As another Sea Grant fellow pointed out, a whole lot has changed since our last blog posts. The world seems to have turned upside down in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Our everyday lives have shifted dramatically, and many of us are struggling with a deep sense of uncertainty for what is to come. This pandemic has put a spotlight on our national (as well as personal and global) need to improve flexibility, planning, and response times in the face of current and future change. On both large and small scales, we are asking ourselves how we can best cope with the crisis at hand, and how we can better prepare for inevitable future surprises. On the bright side, this tumultuous time has created space for us assess our societal, personal and professional priorities as we move forward. In particular, many of us are looking for tools to increase our resilience and adaptive capacity as time goes on.

Although completely unrelated to Covid-19, the members of the Oregon Marine Team at The Nature Conservancy (TNC) have been asking similar questions for almost a year, but in the context of fisheries. The team has been examining uncertainty through a process known as Scenario Planning, focused on the future of West Coast fishing, management, and the communities that rely on that industry.

Scenario planning is a tool that was first created by the US military during World War II, later modified for use by the oil industry, and more recently been applied to a wide array of business and agency contexts, including the stock market and natural resource management. In essence, this method explores what may happen under different sequences events by helping managers and decision makers develop strategies to meet uncertainty. Under the direction of a consultant, TNC is collaborating with the Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) (https://www.pcouncil.org/) on a multi-phase Scenario Planning process that examines climate change scenarios and related impacts on fisheries along the California Current System (CCS).

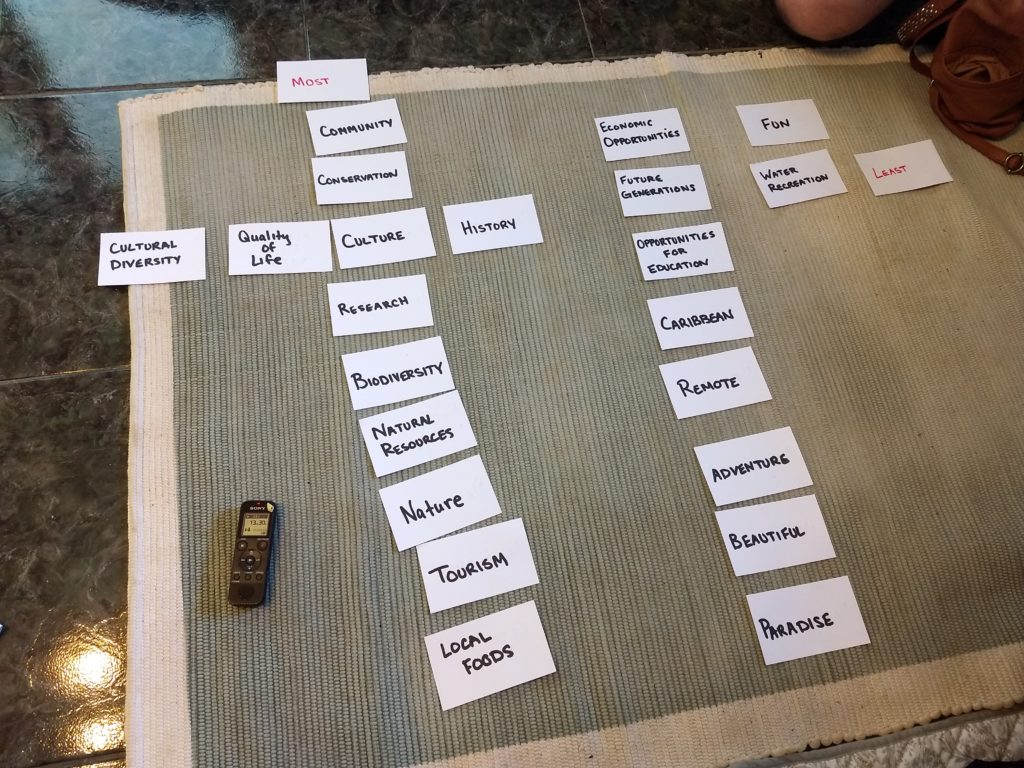

The process includes 5 distinct steps: “Establish, research, create, validate and apply”. The “create” phase involves a scenario planning workshop, which took place in January 2020 in Orange County, California. The workshop brought together upwards of 80 West Coast fishermen, managers, tribal members and scientists for an interactive brainstorming session that examined a central question: How will climate change impact West Coast species and coastal communities over the next 20 years (PFMC 2020)? By the end of the workshop, participants had successfully created a set of narratives (or scenarios) describing what the marine environment may look like in 2040. Since then, these scenarios have been refined and results will be ground-truthed and further researched over the coming months. (If you’re interested, click here for detailed information on the January workshop.)

As the PFMC process continues, The Nature Conservancy has launched another Scenario Planning initiative, this one with the state-managed Dungeness Crab fishery in Oregon. While Covid-19 related complications have delayed the process, we are deep into the planning process and we are remaining flexible in regards to timing as we plan our next steps.

There are a number of reasons why TNC is focusing their efforts on scenario planning for the Dungeness crab fishery:

- The fishery is important to coastal economies: In most years, Dungeness crab is the most economically important single species fishery in Oregon and across the entire US West Coast (Rasmuson 2013; Lee & O’Malley 2019).

- Dungeness crab stocks are projected to be impacted by a series of climate change components over coming decades, including marine heat waves (remember the ‘warm blob’), Hypoxia and Ocean Acidification (OA), and Sea Level Rise.

- In addition, the fishery itself will likely be impacted by increasing harmful algal blooms (HABs) containing toxic diatoms like domoic acid (DA), as well as whale entanglements.

These factors of change point to a significant access reduction to the fishery in coming decades, which may create ripple effects across cultural and socio-economic aspects of Oregon’s fishing communities. Over the coming year, TNC will utilize existing data, and gather knowledge from fishermen, managers, scientists and community members, to develop scenarios for fishing communities 20-50 years from now. The goal of this process is to contribute to future planning and decision-making abilities in coastal communities, in management and in the fishing industry itself (Borggaard et al 2019; Peterson et al 2003).

Like many of us in the environmental sciences, I’m keenly aware of how climate change components are creeping into local, regional and global systems, and I am awaiting more dramatic shifts in my lifetime. Even so, the projected state of our planet in 20, 50 or 100 years remains abstract in my mind because of my limited scope of direct experience. Although COVID-19 may not be related to climate change, both pandemics and climate change have been intricately studied, and experts openly share concerns of issues to come. Our global response to Covid-19 spotlights how ill prepared we are for the abstract, but inevitable. For me, this pandemic has cemented the importance of tools like scenario planning to better prepare for our future.

References:

Borggaard, D & Dick, D & Alexander, M & Bernier, M & Collins, M & Dudley, R & Griffis, R & Hayes, S & Johnson, M & Kircheis, D & Kocik, J & Morrison, W & Saunders, R & Sheehan, T & Saba, Vincent. (2019). Atlantic salmon climate scenario planning pilot report. 10.13140/RG.2.2.20713.85604.

Lee, E and O’Malley, K (2020) Big Fishery, Big Data, and Little Crabs: Using genomic methods to examine the seasonal recruitment patterns of early life stage Dungeness crab (Cancer magister) in the California Current Ecosystem. Frontiers in Marine Science. Doi. 10.3389/fmars.2019.00836

Peterson, G., Cumming, G., Carpenter, S. (2003) Scenario Planning: A tool for conservation in an uncertain world. Conservation Biology. Vol. 17, No. 2.

Pacific Fishery Management Council (2020) Follow up from a workshop co-sponsored by The Nature Conservancy and the Pacific Fishery Management Council in support of the Fishery Ecosystem Plan Climate and Communities initiative. https://www.pcouncil.org/documents/2020/03/g-3-a-supplemental-cci-workshop-presentation-1-follow-up-from-a-workshop-co-sponsored-by-the-nature-conservancy-and-pacific-fishery-management-councilin-support-of-the-fishery-ecosystem.pdf/

Rasmuson L (2013) The biology, ecology and fishery of the Dungeness crab, Cancer magister. Adv Mar Biol 65:95–148