In the archival field, enhanced description practices support biographical work. This includes the ongoing News and Communication Services Records (RG 203) biographies project that seeks to further facilitate access and searchability of former faculty, staff, and students through the identification of individuals listed in Series 4 of the collection through the addition of short biographies to the collection’s finding aid. For each individual listed, the series contains biographical documents like resumes, newspaper clippings, and obituaries that include key points about an individual’s life and career. These points are often references to an individual’s positive contributions to society. As a result, the biographical documents, and biographical work these documents support, may overlook harmful causes that an individual supported or actively participated in.

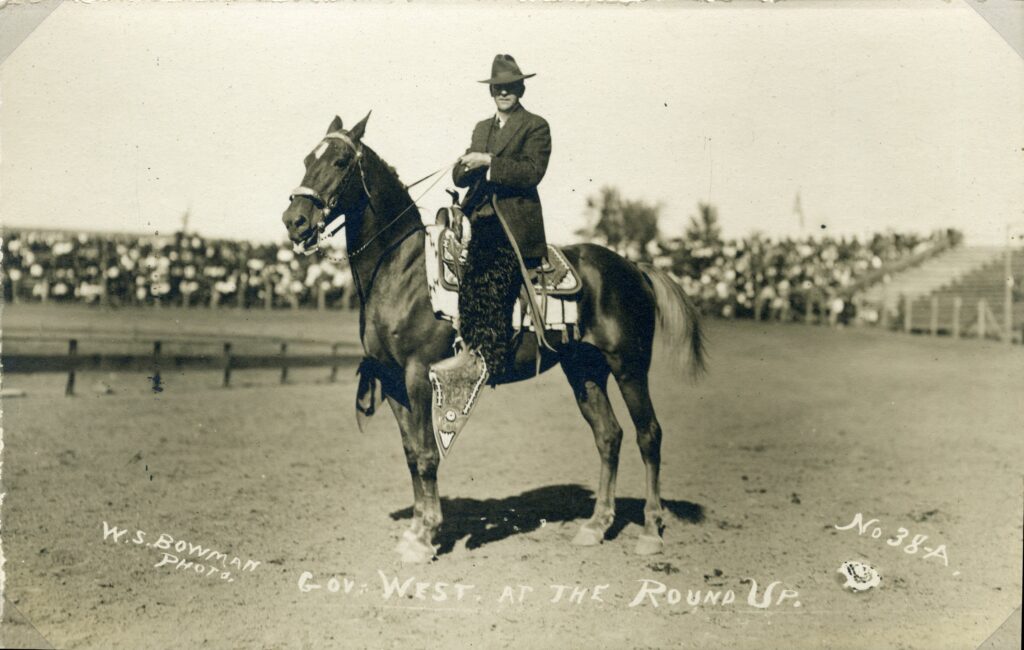

This is true of Oswald West, who served as the fourteenth governor of Oregon from 1911 to 1915. West did not attend nor work at Oregon State, but West Hall (former women’s residence hall and current Honors College Living-Learning Community) is named after him. RG 203 contains only one document related to West: a pamphlet advertising West Hall upon its construction in 1960. It reads:

Governor West’s single term of office has been called the most colorful in Oregon’s history… he laid plans for the state’s present highway system. He pushed through the farsighted legislation providing for public ownership of Oregon’s 400 miles of ocean beaches. He is responsible for the workmen’s compensation law, funds for caring for homeless children and foundlings, creation of the State Board of Control, and other notable changes. Students of this and future generations who make West Hall their campus home may well be proud to live in a hall named for such a vigorous, courageous, dedicated leader as the Honorable Oswald West.1

However, in performing routine research outside of SCARC’s collections to write West’s biography, I discovered that he was also a proponent of eugenics law in Oregon. More specifically, he passed Oregon’s first forced sterilization law.

Forced sterilization allowed physicians to sterilize patients without their consent, rendering the patient infertile. As a whole, sterilization laws were fundamentally Eurocentric and their racist foundations were concerned primarily with improving the white race by preventing the reproduction of individuals lawmakers saw as “unfit” to bear children.2 In today’s terms, the victims of forced sterilization laws in the twentieth century included people of color, the mentally and physically disabled, criminals, the impoverished, queer people, and sexually active women.

Eugenics was amongst West’s primary concerns during his term as governor. In his inaugural message to Oregon’s legislative assembly in 1911, West wrote, “Degenerates and the feeble-minded should not be allowed to reproduce their kind. Society should be protected from this curse.”3 He further wrote, “The State has been shocked by the recent exposures to degenerate practices… These degenerates slink, in all their infamy, through every city, contaminating the young, debauching the innocent, cursing the State.”4 West’s proposed solution was the implementation of eugenics laws. “Sterilization and emasculation offer an effective remedy,” he wrote. “I would recommend, therefore, that a statute be enacted making it the duty of our State penal and eleemosynary [adjective: related to charity; charitable] institutions to report all apparent cases of degeneracy to the State Board of Health. It should be made the duty of the said board to cause investigation to be made and, if the findings warrant, to cause such operations to be performed as will give society the protection it deserves.”5 West launched a “crusade against vice” in 1912 and thus urged the Oregon legislature to investigate “degeneracy.” 6

West was influenced by proponents of eugenics at the time. Bethenia Owens-Adair was a doctor and advocate for forced sterilization in Oregon. She authored and worked with Representative L. G. Lewelling to push a eugenics bill through the Oregon House of Representatives. On February 18, 1913, Governor West signed into law House Bill No. 69. The bill gave “broad powers to the state to sterilize citizens, regardless of the recommendations of medical, religious, and legal authorities.”7

The bill was signed into law in part due to the Portland Vice Scandal in 1912, which revealed a subculture for gay men in Portland, Oregon. The scandal “led states throughout the Northwest to strengthen and expand sodomy laws and, in the 1910s and 1920s, to encourage Oregon, Washington, and Idaho to adopt Eugenics programs that prescribed the sterilization of sex offenders.”8 By 1913, “sodomy” and the related phrase “crime against nature” in Oregon encompassed a breadth of sexual activity that was not completely defined, but did include oral and anal sexual activity.9 By categorizing these activities as sexual offenses, and by association, gay men and lesbian women as sex offenders, they were targeted as criminals. Moreover, the American Psychological Association “considered gender and orientation variance a mental illness in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” until 1987.10 Therefore, members of the queer community were also targeted for forced sterilization because the state considered their identity to be a mental illness.

The 1913 bill went to referendum due to lobbying by the Oregon Anti-Sterilization League and did not pass. Thus, it was repealed before it went into effect.11 The Oregon Anti-Sterilization League is credited for swaying public opinion on this vote. However, a new forced sterilization law was passed in 1917 by West’s successor, Governor James Withycombe, who stated:

I am more and more convinced that the reproduction of the mentally unfit is absolutely wrong. Through our shortsighted inaction we are populating our State with imbeciles and criminals, insuring ever-increasing public expense and opening the way for disease, sorrow and tragedy for generations yet unborn… To mend this situation, I earnestly urge the passage of a sane Sterilization Act.12

Withycombe, while not included in the contents of RG 203, was involved with Oregon State prior to serving in the state government. In 1898, he joined the Oregon State staff as a professor of agriculture, and in 1908, was appointed Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station. Withycombe Hall is named after the fifteenth Oregon governor.

The bill passed by Withycombe did not require a referendum and the state formed the Board of Eugenics. This board included superintendents from state institutions like the Oregon State Hospital, the Eastern Oregon State Hospital, the State Penitentiary, and the State Institution for the Feeble-Minded. The board reviewed quarterly reports of inmates recommended for forceful sterilization.13 Inmates recommended for sterilization were those who were “feeble-minded, insane, epileptic, habitual criminals, moral degenerates, and sexual perverts. Habitual criminals were defined as those who have been convicted three times or more of a felony in any state, while moral degenerates and sexual perverts partly included homosexuals and promiscuous teenage girls.”14

Initially, the law did not require consent from individuals recommended for forced sterilization, but in 1923, state legislature changed the process for sterilization so that, “inmates and patients would be sterilized only if they consented or if a court determined that they should be forcibly sterilized.”15 Oftentimes, though, sterilization was used as a precondition for allowing individuals to leave state institutions. Thus, individuals often agreed to undergo sterilization if it allowed them their freedom. The statue was revised several more times through the twentieth century, stripping eugenic language and instead emphasizing prospective parents’ inability to care for children in 1935, removing additional eugenic language in 1967, and limiting the class of state wards considered for sterilization to mental hospital inmates in 1970.16

State-sponsored eugenic sterilization ended in 1983.17 From 1917 to 1983, over 2600 individuals were forced to endure sterilization in Oregon.18 While SCARC does not hold records directly related to Oswald West’s involvement in Oregon’s eugenics movement, enhanced descriptions for collections like RG 203 can give a more nuanced and informed approach to studying him, especially given his relationship with Oregon State.

Grace Knutsen is the former lead student archivist at Special Collections and Archives Research Center. She is an Oregon State alumna and Master of Library and Information Science student.