This post references a report from the United States War Relocation Authority Reports. The collection is comprised of more than fifty mimeographed reports detailing the operation of War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps used to house Japanese American incarcerees during World War Two.

Series 2 is composed of 14 “notes” published by the Community Analysis Section (CAS) between 1944 and 1945. The notes are short reports on subjects including marriage customs, healing practices, and “block” self-governance within the concentration camps. The notes series includes several reports documenting interviews with incarcerees. It also includes a series of reports on areas within the exclusion zone including Fresno County, Imperial Valley, the San Francisco Bay Area, and San Joaquin County.

The item reference in this post (Box-Folder 1.20) and the entire contents of the collection have been digitized and are available upon request.

After the United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, racism and xenophobia against Japanese Americans grew. White Americans suspected Japanese Americans of espionage and loyalty to the Japanese Empire. In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt infamously established internment camps through Executive Order 9066, intending to imprison Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Importantly, this order targeted not only Japanese immigrants (“Issei”), but also their descendents who were United States citizens (“Nisei”).

This mass incarceration caused major organizational chaos. Military commanders were given the authority to create incarceration centers for individuals considered a threat to national security. Soon after, Roosevelt signed another executive order into effect, establishing the War Relocation Authority (WRA). More than 125,000 Japanese Americans were first removed from their homes to military-run “assembly centers”, and later, to one of the ten prison camps established by the WRA.

Between 1942 and 1946, the WRA Community Analysis Section published reports intended to document the social backgrounds of the prisoners and their reactions to conditions in the camps.

Among these reports is a document dated January 15, 1944, entitled “From A Nisei Who Said ‘No’”.

In the document, a community analyst working at the Manzanar internment camp in California documents an exchange between a young Japanese American man and a hearing board authorized to pass upon questions of segregation at the camp.

The analyst writes that the young man, who remains unnamed through the document, replied “no” to Question 28 of the Army registration form submitted to all male evacuee citizens in 1943. The question read, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”

The question was controversial. By asking Japanese Americans to forswear allegiance to the Japanese emperor, to answer “yes” would imply that they had previously held allegiance to this foreign power. This implication stung Issei and Nisei who held no such allegiance. However, by answering no, a Nisei revoked their American citizenship. The man’s answer resulted in a hearing wherein board members confirmed that the man was an American citizen who had always lived in the United States and that he understood the consequences of answering “no”.

In the hearing, he stated:

“I thought that since there is a war on between Japan and America, since the people of this country have to be geared up to fight against Japan, they are taught to hate us. So they don’t accept us. First I wanted to help this country, but they evacuated us instead of giving us a chance. Then I wanted to be neutral, but now that you force a decision, I have to say this. We have a Japanese face. Even if I try to be American I won’t be entirely accepted.”

The hearing ended shortly after, when he had convinced the board that his mind was made. He was not willing to serve a country that had imprisoned innocent American citizens. The community analyst who authored the report reached out to the man for a fuller statement on his views, a portion of which are included below:

“Before evacuation, all our parents thought that since they were aliens they would probably have to go to a camp. That was only natural – they were enemy aliens. But they never thought that it would come to the place where their sons, who were born in America and were American citizens would be evacuated. We citizens had hopes of staying there because President Roosevelt and Attorney General Biddle said it was not a military necessity to evacuate American citizens of Japanese ancestry.”

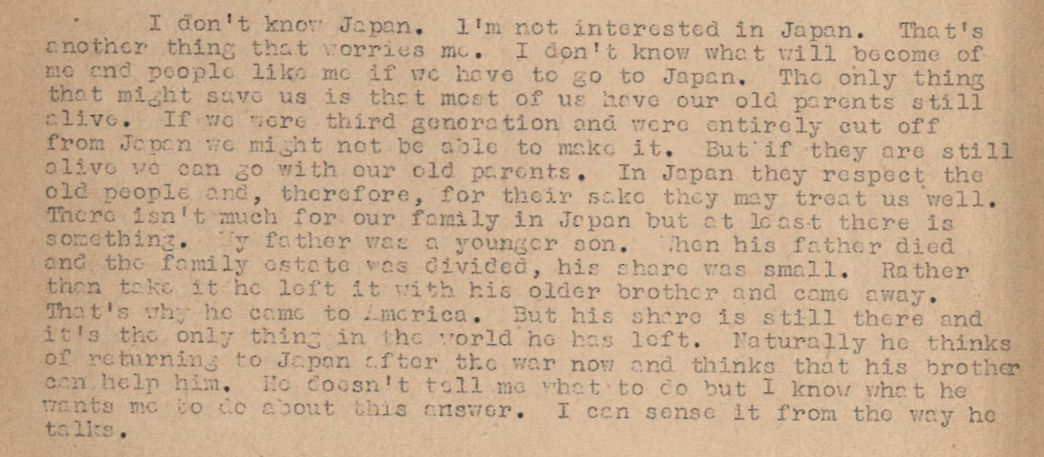

“I don’t know Japan. I’m not interested in Japan. I don’t know what will become of me and people like me if we have to go to Japan.”

“I tell you this because it has something to do with my answer about that draft question. We are taught that if you go out to war you should go out with the idea that you are never coming back. That’s the Japanese way of looking at it.”

“In order to go out prepared and willing to die, expecting to die, you have to believe in what you are fighting for. If I am going to end the family line, if my father is going to lose his only son, it should be for some cause we respect. I believe in democracy as I was taught in school. I would have been willing to go out forever before evacuation. It’s not that I’m a coward or afraid to die. My father would have been willing to see me go out at one time. But my father can’t feel the same after this evacuation and I can’t either.”

This report is a rare occurrence, wherein a Japanese American was able to voice their views to a government authority. Moreover, the young man’s decision and statement represents radical protest by Japanese Americans against United States policy during the war. The young man was not alone; it is estimated that twenty percent of all Nisei responded “no” to Question 28. The WRA also found a sharp increase in the number of repatriation and expatriation applications from Nisei and Issei during this time. By refusing to serve the United States, these individuals were practicing the very democracy they had hoped to defend.

This post is contributed by Grace Knutsen. She is a student archivist at the Special Collections and Archives Research Center. She studies history, French, and German.