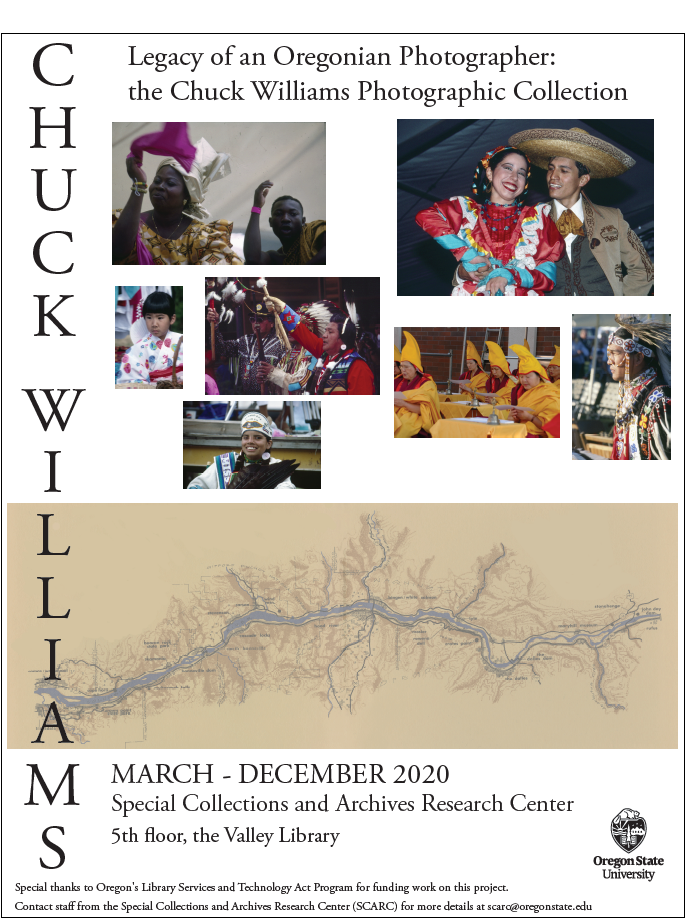

“Legacy of an Oregonian Photographer: the Chuck Williams Photographic Collection” highlights the work of Charles Otis “Chuck” Williams II (1943-2016), an Oregon-based professional photographer and environmental activist. He was of Cascade Chinook descent and for many years a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

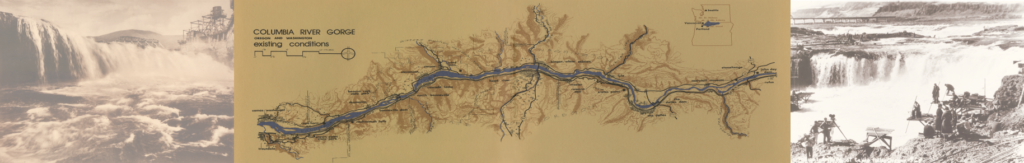

Prior to his passing, Williams donated his materials to both Willamette University (WU) and Oregon State University (OSU). Willamette University’s collection, the “Chuck Williams Activist Papers,” documents Williams’s integral role in preserving the Columbia River Gorge, and highlights his leadership in the grass-roots activism that led to the National Scenic Act. Oregon State University’s “Chuck Williams Photographic Collection” is a part of the Oregon Multicultural Archives, which is dedicated to preserving and celebrating the histories of communities of color in Oregon. The photo collection includes thousands of slides, prints, and digital photographic materials that showcase Williams’ prolific career as a photographer during the 1980s-2000s. The photographs document the wide variety of cultural celebrations, landscapes, and tribal communities in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest. Together, these materials provide a unique perspective on Oregon, including topics such as environmental and political science, photography, and the state’s multicultural history.

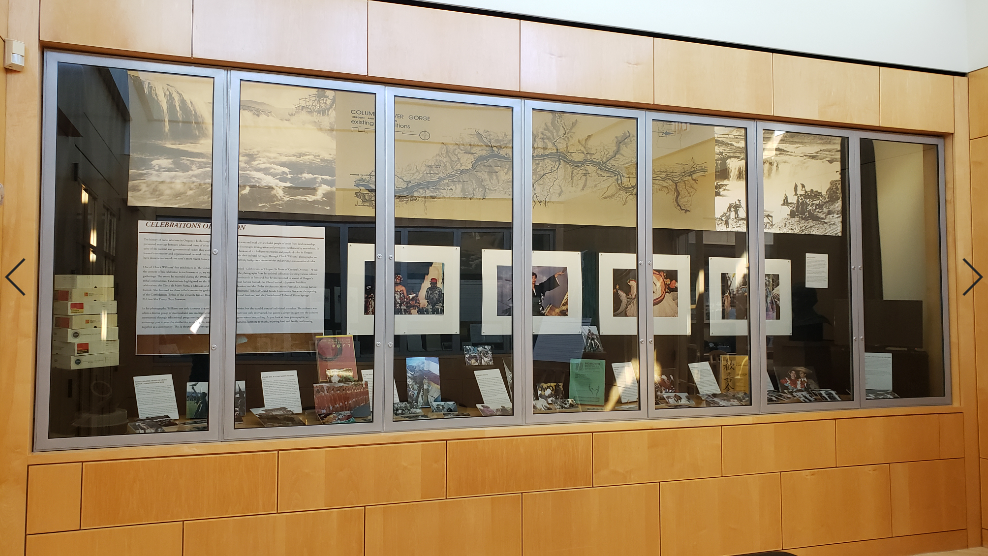

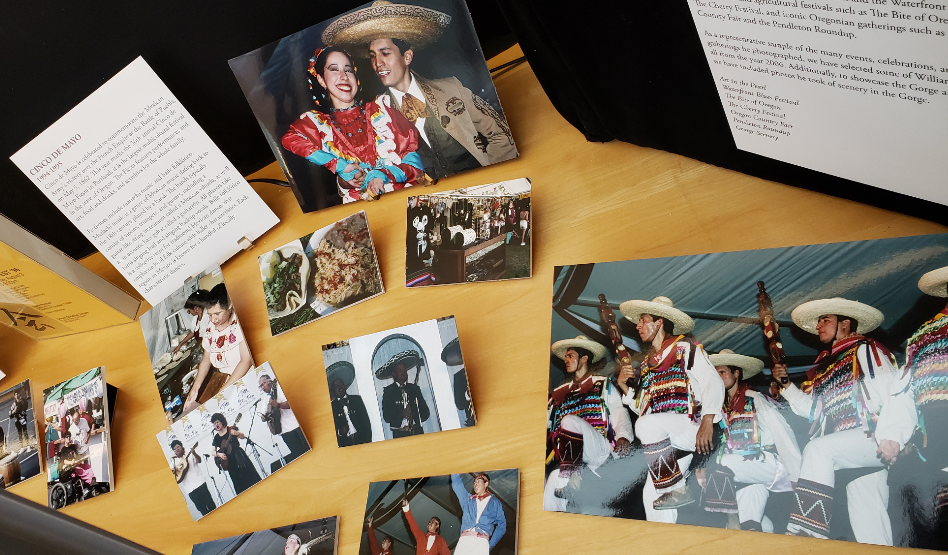

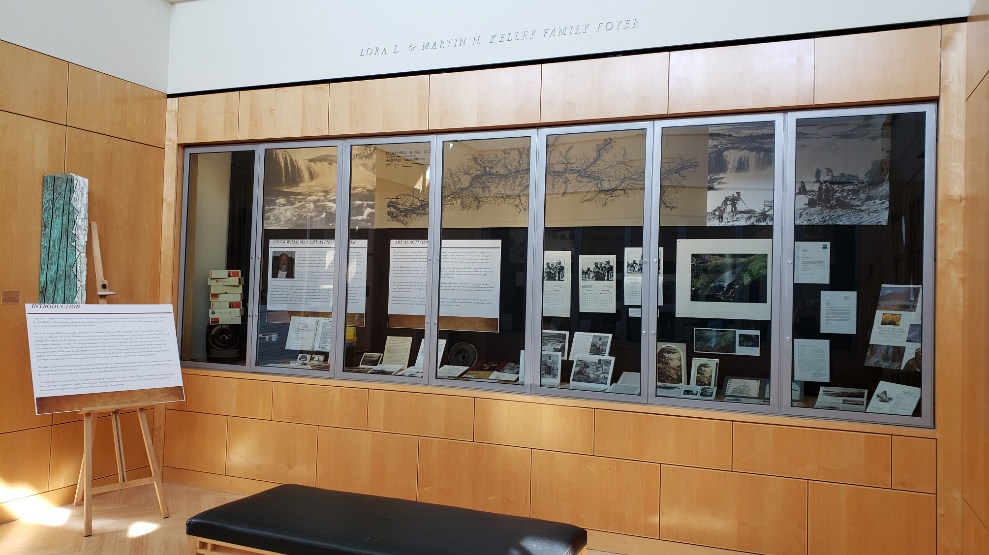

This exhibit begins with a “behind the scenes” look into Williams’ life as a professional photographer, including his cataloging process and the equipment he used to document the events, people, and places he photographed. It also demonstrates the many ways a photographer shares their work and first-hand knowledge of a community through exhibitions, lectures, books, and more.

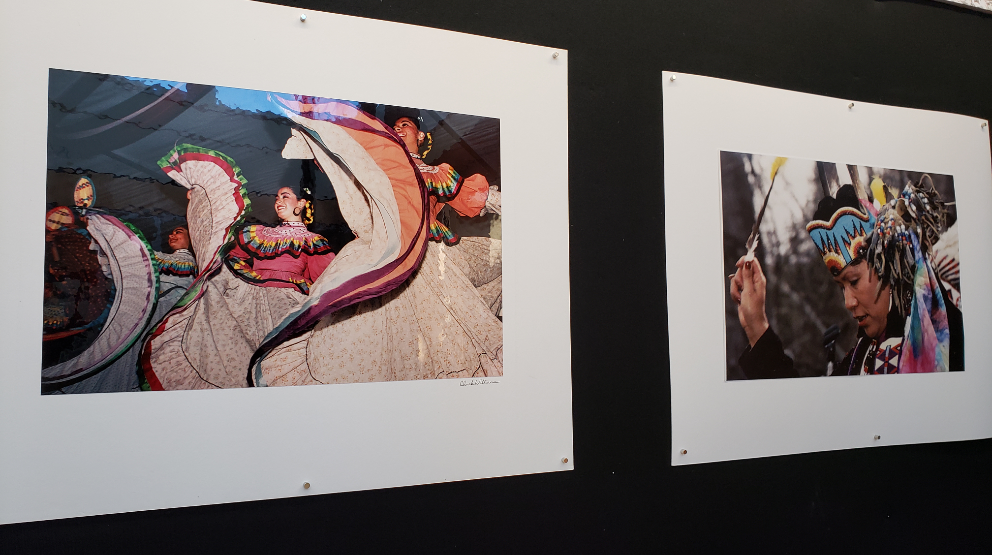

The exhibit then focuses on Williams’ photographs representing communities of color in Oregon. Williams traveled the state photographing a variety of Oregon’s Indigenous, Latinx, Asian-American, and African-American community events. These rich and varied images provide a visual context to Oregon’s increasingly diverse history and ongoing cultural heritage.

Chuck Williams was a direct descendant of Chief Tumulth of the Cascades Tribe, who signed the (ratified) 1855 Treaty of the Willamette Valley. In addition to his work as a photographer, Williams worked as publications editor and public-information manager for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission in Portland, co-founded and managed Salmon Corps, and was the former national parks expert for Friends of the Earth. He also started the campaign for a Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, and his land donation is now the Franz Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

For much of his life Williams was based in The Dalles area, and by virtue of his work as a professional photographer, he attended events, festivals, and celebrations predominantly in Oregon and Washington. He sought out opportunities to document these events and his career flourished; in time, several organizations invited him to be one of their official photographers.

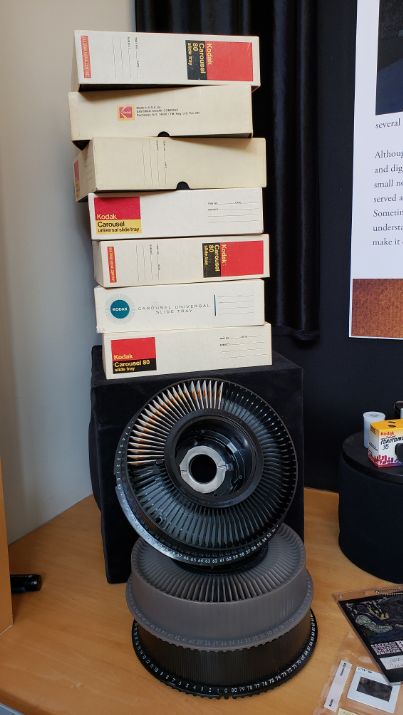

Although Williams’ primary medium in the 1980s and 1990s was slide photography, he adapted to new technologies and soon produced print and digital photography. To track his work, Williams labeled his images and used a system of alphanumeric codes; while in the field, he carried small notebooks, spare flyers, and scrap paper to note the pictures he took and their matching codes. Williams created a master index that served as a complete catalog of his work; each entry in the index included a code, a narrative description of the photo(s), and the date(s). Sometimes the photographic material only included a code and minimal textual information, so this index is instrumental in completing our understanding of the images. While most of his slides were kept in slide boxes, he also curated his work by selecting slides to place in carousels to make it easier for his own review and to share his work with others.

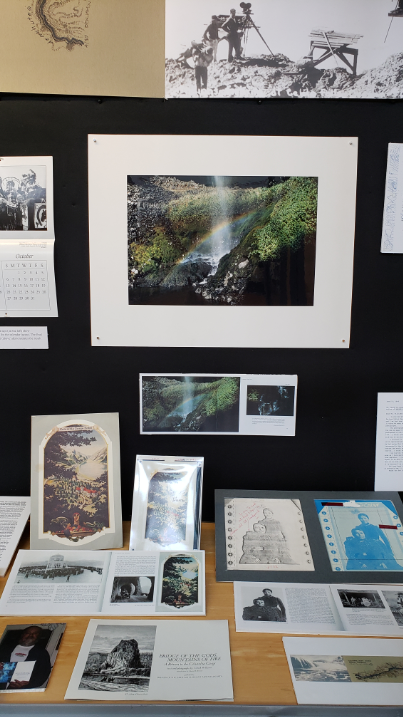

“Chuck” means “river” in Chinook Wawa. In 2007, Chuck Williams wrote, “undammed rivers are not only important to me personally, but also seem like an appropriate symbol of the enduring River People.” Throughout his life, Williams was a dedicated advocate for the rights of Indigenous Peoples of the Columbia River Gorge area. His core values informed his artistic and professional endeavors. As a part of his activism, he created art that celebrated and supported the River People, while also educating the broader community about important issues.

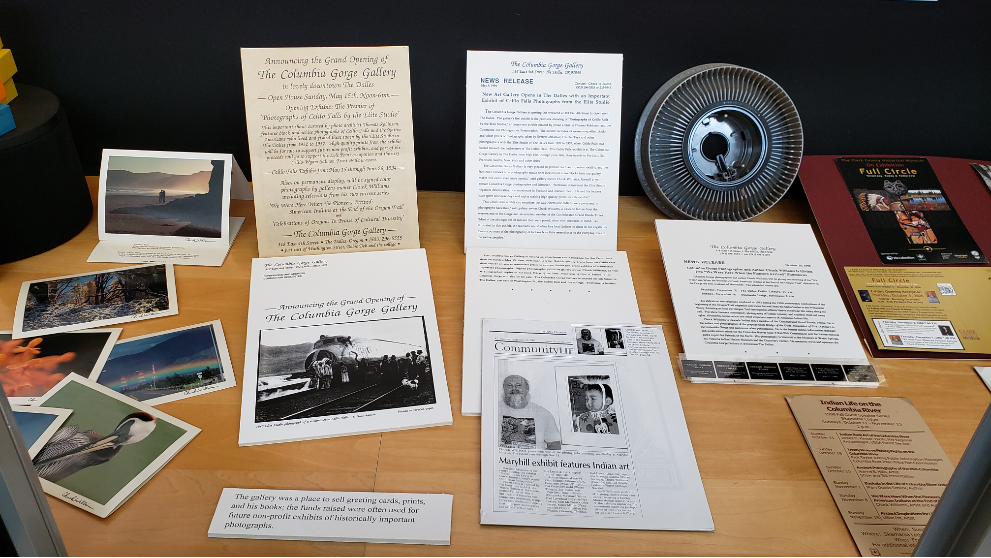

In 1994, Williams opened his gallery, The Columbia Gorge Gallery, which was located downtown in The Dalles, Oregon. He exhibited his own photographs, along with the works of other artists. While the Gallery was a space for people to see his work, Williams also participated in community activities in order to reach a wider audience. He gave lectures and slide shows for speaker series and special events, and his photography was shown in numerous museums and galleries, predominately in Oregon.

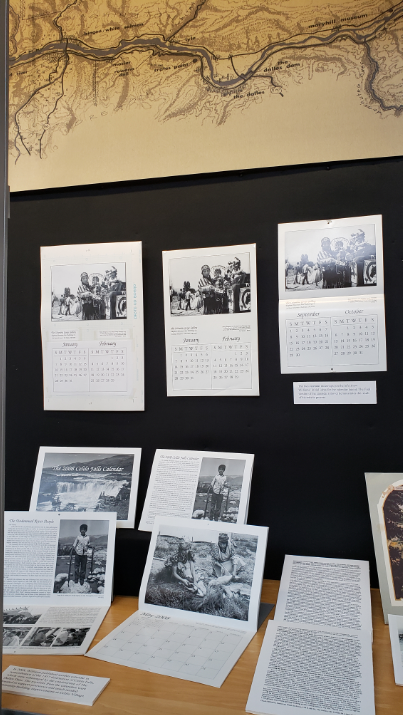

After the success of the Gallery’s first exhibit, “Photographs of Celilo Falls by the Elite Studio,” Williams created a companion calendar in 1996 that featured selected images from the exhibit; he published another calendar in 2008. In the introduction to the 1996 calendar Williams wrote, “I hope this calendar will remind people of what was lost by our taming of the great river and will help the river Indian community of which I am a part flourish.”

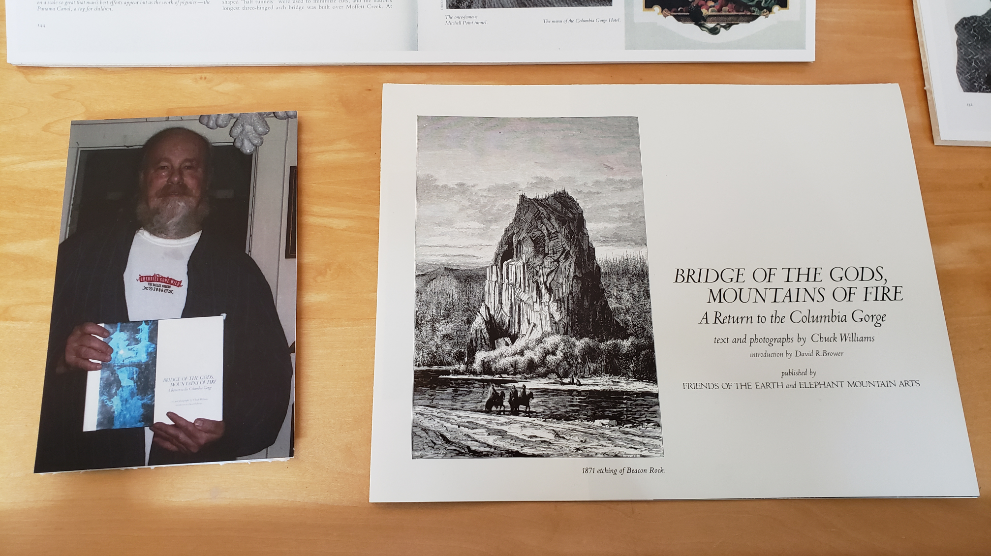

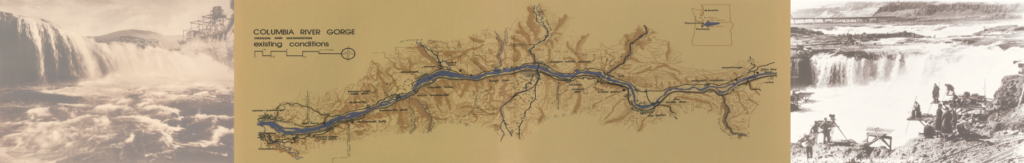

Williams published the book Bridge of the Gods, Mountains of Fire: A Return to the Columbia Gorge in 1980. In the book, he combined traditional Indigenous stories, his own ancestry, and historical and geological records. Williams complimented the historical images with his own contemporary photographs, effectively bridging past and present controversies in the Gorge

The history of racial relations in Oregon is both complicated and shameful. Past state and local laws excluded people of color from land ownership, prevented marriage between whites and those of other ethnic backgrounds, and discouraged immigration and permanent settlement by non-whites. In spite of the societal and governmental racism endured – or perhaps in part because of it – Indigenous peoples and people of color in Oregon formed community and organizational networks to support each other and to retain their cultural heritage. Through Chuck Williams’ photographs, we have documentation of our state’s more recent history, highlighting Oregon’s thriving Indigenous communities and growing communities of color.

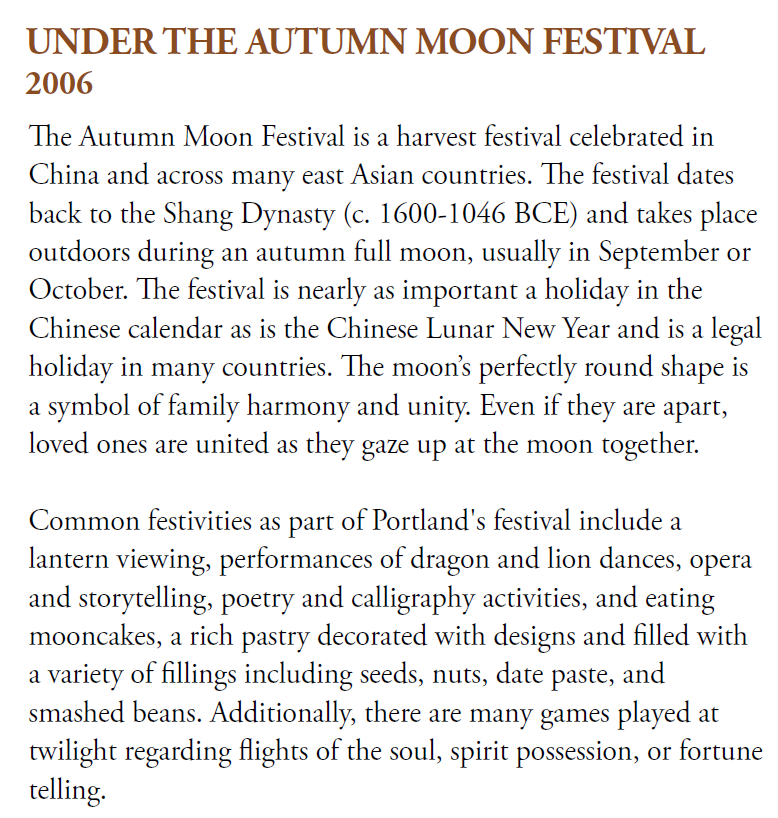

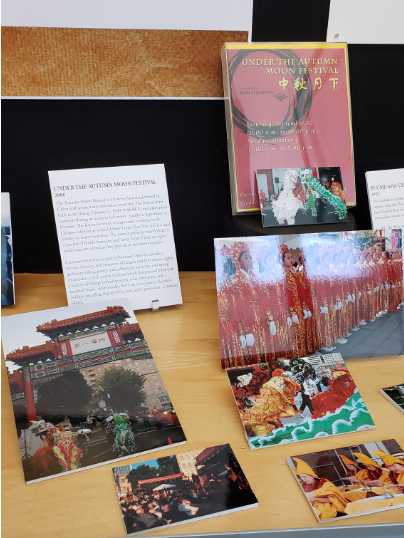

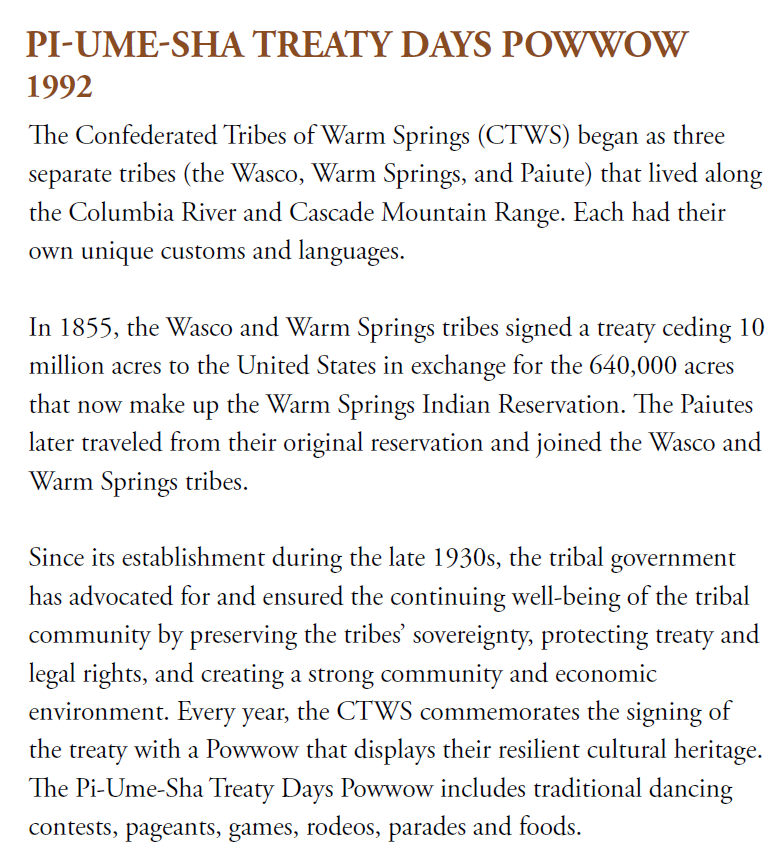

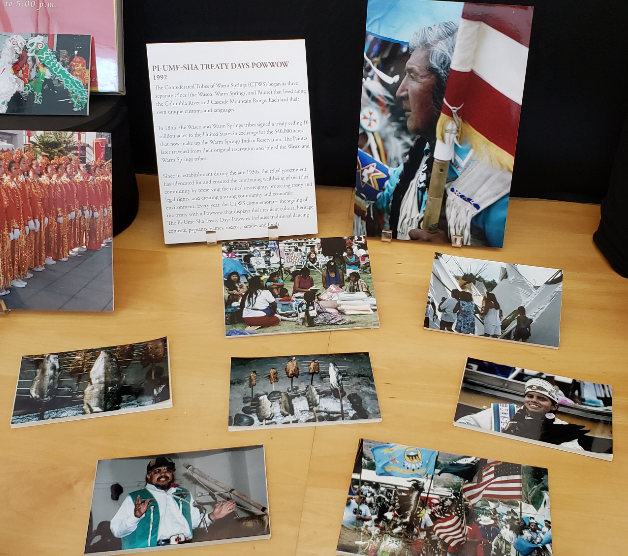

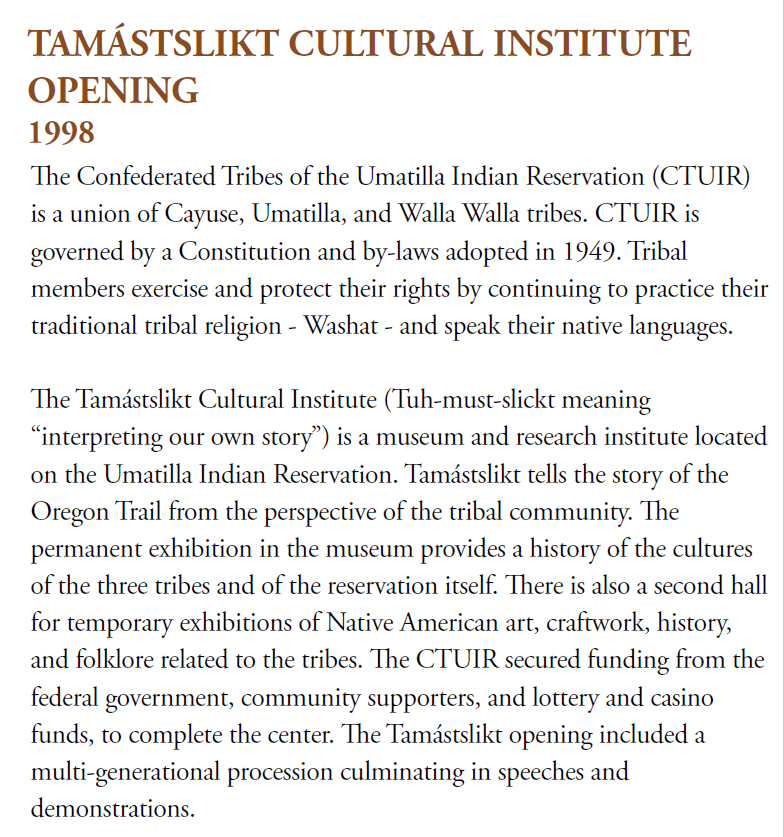

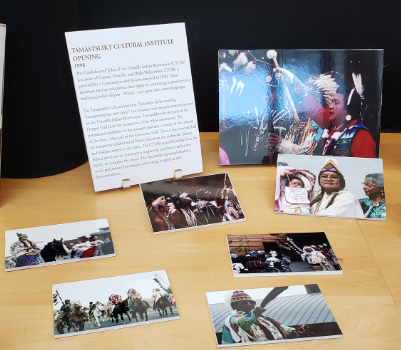

One of Chuck Williams’ first exhibitions in The Columbia Gorge Gallery was titled “Celebrations of Oregon: In Praise of Cultural Diversity.” While the content of his exhibition is not known to us, we were inspired to showcase the photographs from his archival collection featuring various cultural gatherings. The events he recorded during the 1990s and 2000s were held predominantly in Portland, but he also traveled to several of Oregon’s tribal communities. Celebrations highlighted include the Homowo Festival, a Ghanian harvest festival; the Obon Festival, a Japanese Buddhist celebration; the Cinco de Mayo Fiesta, a Mexican and Mexican-American celebration, and the Under the Autumn Moon Festival, a Chinese harvest festival. Also featured are three tribal community gatherings including the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community Powwow, the opening of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs Pi-Ume-Sha Treaty Days Powwow.

In his photographs, Williams not only captures dynamic performances and activities, but also candid shots of individual attendees. The audience was often a diverse group of multicultural and multigenerational people; attendees were not only entertained, but gained a deeper insight into the cultures represented through educational programming, religious ceremonies, and intergenerational storytelling. As you look at these photographs, we encourage you to note the similarities across events, and to observe the people dancing, listening to music, enjoying food and family, and coming together as a community. This is the power of photography and art.

Images from the exhibit are in Oregon Digital