For the given prompt to assess the accuracy of McLuhan’s “hot” and “cold” media theory, I provide the example of NieR Automata — a video game developed by Square Enix — to prove the outdatedness and illegitimacy of categorizations of forms of media by their mandated or assumed level of user participation and “thought”.

To begin, it stands to be noted that I agree wholeheartedly with his statement that the medium is the message. As I will explain through this post, NieR Automata is a piece that would not function to a fifth of a percent as well as it does in storytelling if it were portrayed in any medium other than a video game. It would not work as an art form in the way that it does without the strength and interactivity of the medium in context of its message.

(As a side note, so this doesn’t come off as the heated ramblings of a nerd, it stands to be noted that NieR automata received NAVGTR nominations and awards for “Best Writing in a Drama”, “Character Development”, “Camera Direction”, “Best Score”, and many more. This is a piece of artwork that is internationally acknowledged, despite being frequently ignored due to it’s medium by professionals in the art and design scene.)

To summarize for context, NieR Automata is a game about philosophy that hides its true intention under layers of analysis and attention to detail. It is a game that requires being played through five times, despite giving no mandate that the player do so. On your first playthrough, it intentionally presents itself as a very non-serious arcade-style game, wherein you are an android with a sidekick that is deployed to save the earth by killing robots: A very stereotypically fighter-type videogame that is meant to be played for fun with no deeper meaning. In this first playthrough, the medium itself is red hot. Everything is provided for you, and you are — by design — intended to play through it mindlessly for simple enjoyment with little work needed to be done for interpretation or “definition”. When you beat the game, there is a small hint saying you should play it again, but — by design — you feel satisfaction having done your job, beat the bad guys, and having needed little participation other than holding the controller to have enjoyed the piece.

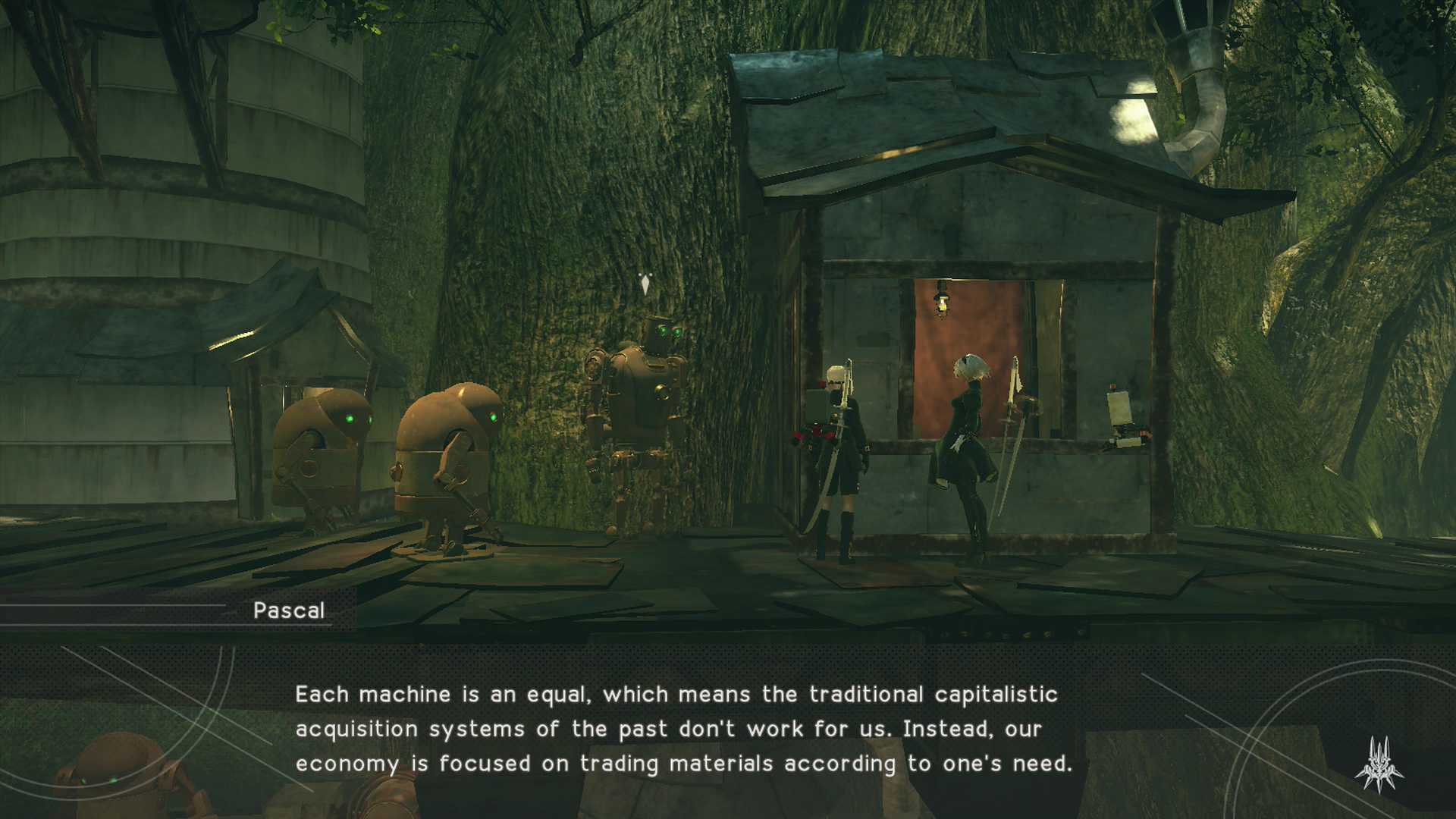

It is in pressing the “New Game” button that the application of McLuhan’s theory falls apart, and the true nature of the piece reveals itself. This time, you play as the goofy sidekick, who is useless in combat (the purpose of the original playthough) but has the added “gimmick” that he can read the robot’s thoughts. It is through playing through the game again as the useless sidekick that the meaning of the story gets flipped on it’s head, and the dark philosophical underbelly of the piece becomes clear. Through an understanding of your opponents’ thoughts, you learn that they view you identically to how you view them — and that there are a variety of different schools of ethical thought at play in how you determine your actions through the game, through deep analysis of rule-utilitarianism through the applications of socialism versus laissez-faire capitalism. While it is far too complicated for me to continue to summarize, I fully encourage you to research it — or just play it — to truly understand the depth of this game, and how it intentionally causes the viewer / player to analyze their own thoughts of the world outside of the game, their political beliefs, their ethics and definition of virtue, and even in a final masterstroke, question whether or not videogames can be used as a true and respected art form, or if they are limited to being just silly things meant for enjoyment — all through the relationships of the various parties, factions, and characters within the same plotline, played through multiple times from multiple perspectives. I consider it the video game equivalent of Ender’s Game in relation to its sequels. A true masterstroke.

It is at this point that I would entirely view this game as an example of the coldest piece of media I have ever experienced, despite previously and concurrently being an unimaginably hot piece of media. Not only are you experiencing it in “high definition”, but it now requires you to analyze your views of life, research various political and ethical topics, and fully call into question your ethical views on psychological concepts like in-group and out-group and how they apply to your own life. Not once have I ever experienced even a book, as a frequent reader of philosophy, ethics, and psychological theory, that has called such active participation and interpretation (to such a degree as the internal analysis of self.) as this video game.

In the same manner that this video game proves that any medium can be either infinitely cold or infinitely hot by McLuhan’s theories, I put forward the claim that this is only one example from the infinite possible examples that the “hotness” or “coldness” of a medium is decided entirely by it’s use and by the level of participation put forth by the viewer themselves, based upon the infinite complexities of the persona that lead them to that viewing of that media. A book can either be low definition and require high user participation, but could also be a book designed as to be high definition in a masterstroke to defy the medium. A movie could be considered hot, but if it is a movie designed to call into question the world itself and call in outside thought and personal interpretation to fully understand the levels of detail and complexities of itself, does that not make it also cold?

It is for this reasoning that I explain that McLuhan’s theory of hot and cold are completely irrelevant and in many ways restrictive to the content creators of every medium — an attempt to categorize and minimize the infinite complexity of the human mind and ability to make individual meanings of every medium from the viewer, and a limitation upon the content creator themselves. It is for this reason that I strongly dislike this theory and disagree with it.

James T. Hartman