Parking issues start with development. Such elements as the location of employers, residences, and the goods and services relative to each other affects the way people access them. The street network for land use developments and uses supporting them affects the need for car trips. A car trip requires at least two parking spaces—one at the beginning and one at the destination. If the trip includes travel around town to a doctor’s visit, getting groceries, obtaining a haircut, and relaxing with a cup of coffee, up to five spaces are required. Most communities are estimated to have five or more parking spaces for every vehicle in the community (19, Chester et al.).

Corvallis devotes one quarter of its total land area to car-dependent infrastructure and rights of way. This infrastructure is a community resource for which there are many uses—commerce and connectivity; public safety; pathway for utilities, waste removal, and environmental services; practice of culture and architecture; and vehicle storage. The infrastructure is valued in the billions of dollars to serve the needs of cars, trucks, buses, and other transportation modes. This infrastructure is expensive to maintain. The Corvallis Transportation System Plan that includes priority projects through 2040 says, “Constructing all 71 High Priority transportation projects in this TSP would cost over $199 million, an amount far in excess of the $63 million in known funding forecasted to be available” (1. TSP 2018:5), and short of the one billion dollars needed for Corvallis’ transportation infrastructure to meet current road quality standards.

The Transportation System Plan estimates the vehicle miles traveled per capita and total VMT traveled over the next 20 years will increase by “approximately eight percent by 2040” (1, TSP 2018:168). This means more greenhouse gases and less health and safety, and requires more parking. Experience shows that it is not possible to out build the demands of car-dependence.

Most often, shared parking at the doctor’s office, grocers, hair stylist, and coffee shop works well. But, at places like an athletic event or concert, a parade or Farmer’s Market downtown, and during holiday shopping parking becomes scarce. Sometimes employers, schools, and businesses do not have enough parking for their clients or employees. This leads people to seek on-street parking. When people park on the street, they sometimes get too close or block resident’s driveways and can obscure the view of drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians. Further, finding parking necessitates driving longer than necessary.

To reduce parking issues requires thinking broadly. A measure showing the reduction in car trips is vehicle miles traveled. This is not simple, since driving offers convenience and timely completion of activities. The approach to car dependency is complex and has to deal with land use planning, allocation of street space, and transportation priorities, along with people’s demand for convenience and saving time.

Since WW II, the development of suburbia has led to car-dependency. Driving is often the only choice and is usually the more convenient and timely choice. Driving is required to go to the doctor and grocery store. The neighborhood no longer has a hair stylist, and the favorite coffee shop is across town.

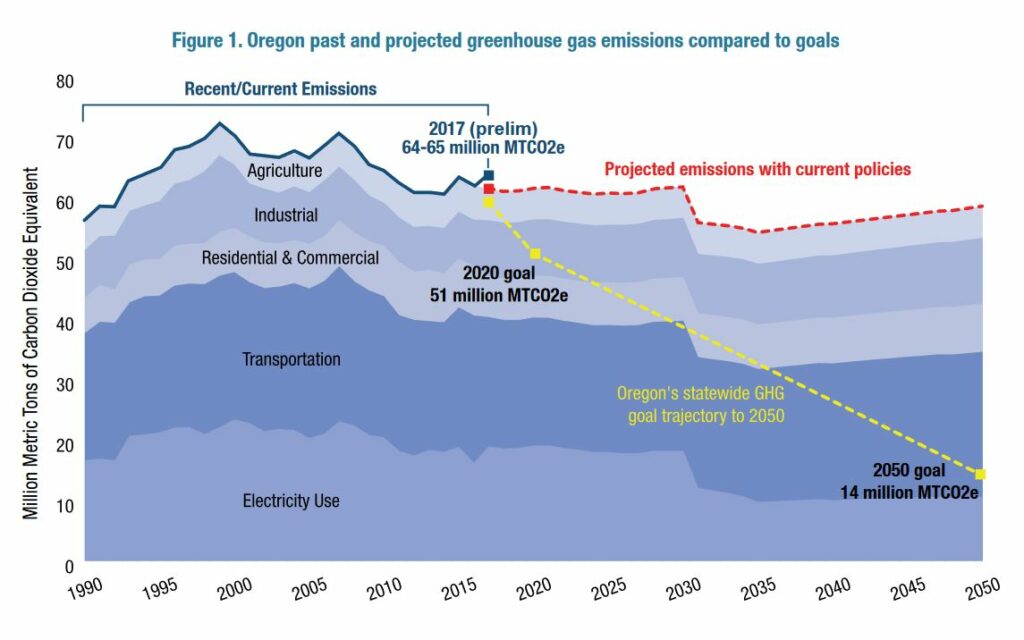

The relation between VMT, greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), and public health and safety is directly tied to transportation, which is the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (2. OGWC). Cars cause the most VMT and GHG. Walking gives the least greenhouse gases the greatest health and safety.

To reduce car trips and VMT and hence parking issues, solutions that consider convenience, timeliness, and affordability may have more success. This is indicated in data on reasons for OSU employee and student primary transportation mode choice (3, OPAL).

If transit and land use can achieve convenient, timely, and affordable modes of transportation and housing, it may be possible to avoid a worsening situation. Where one lives can be easily connected to things like jobs, education, appointments, purchase of goods and services, access to open space and recreation car trips and VMT can be reduced. For example, businesses that provide housing gain customers for their goods and services.

Currently, Oregon is not progressing toward its greenhouse gas reduction goal because of its car dependency. The Oregon Global Warming Commission says, “Transportation GHG emissions have risen during each of the past three years and have grown from 35% of the statewide total in 2014 to 39% in 2016” (2. OGWC). There is no evidence that Corvallis differs in pattern from the rest of Oregon.