I have found that most people feel like COVID has affected their sense of time. This has been especially true for me — the last two years have been marked by beginning graduate school, getting married, a global pandemic, and having a child. The last two years have gone by in a blur. As I write this, some of the students that I began school with are completing their master’s degrees while I am returning from a six-month parental leave of absence after the birth of my first child. I am hoping that this blog post resonates with some folks who do not feel like the “traditional” student, that by speaking more openly about my journey I may be taking a step towards helping myself and/or others find a sense of community and understanding.

Despite everything (decades of education, scholarships, internships, global travel, field work) I still find myself constantly questioning my validity as a scholar, as a contributing member of the scientific community, or even as a Sea Grant Scholar. When the time comes to “perform” and I need to complete an application for funding or write a blog post my instinct is to say to myself that “I haven’t done anything,” that I am unworthy. I know many of my peers feel similarly, where does this seemingly never-ending doubt come from and how do we conquer it? I try to remind myself that thoughts aren’t necessarily facts (in my case, thoughts are frequently not facts), sometimes thoughts are just thoughts. Looking back upon my previous blog posts and reflecting upon this last year as a Sea Grant Scholar, the truth begins to come forward and become clearer… So, what is true?

- Fall 2019: I began my journey as a master’s student in Fisheries Science at Oregon State University two years ago this fall. In fact, I got married on the second day of classes!

- March 2020: A global pandemic has worked its way around the world multiple times over in the past 1.5 years. Which means I was on campus for only six months before everything changed.

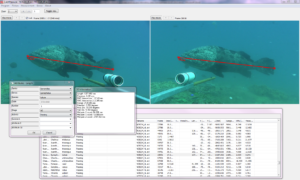

- I formed a collaboration with ODFW Marine Reserves Program and California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program (CCFRP) to sample during their hook-and-line surveys in the fall of 2021.

- December 2020: As mentioned in my previous post, I formally drafted a plan for my research project and successfully defended my research review and formed my committee last winter.

- I got pregnant!

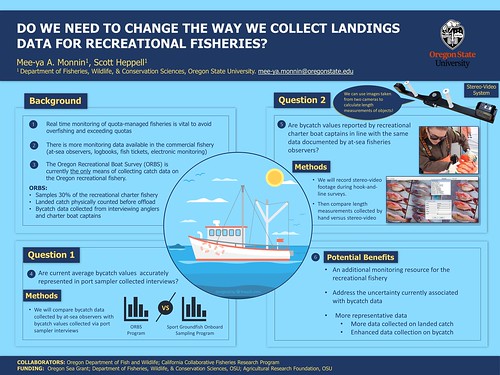

- I started working on part II of my project. Began conversing with ODFW regarding access to Oregon Recreational Boat Sampling (ORBS) program data as well as data collected as part of ODFW’s Sport Groundfish Onboard Sampling (SGOS) program.

- March 2021: I then organized a session for a professional conference, which is a first for me. My lab mate, Claire Rosemond, and I brought together a theme and list of speakers for a symposium at this year’s Oregon Chapter of the American Fisheries Society.

- April 2021: ODFW cancelled their hook-and-line surveys originally scheduled for fall of 2021. ☹ Good thing I secured a collaboration with CCFRP to sample in September! 😊

- May 2021: It may be a small win, but it felt big to me! I won best graduate student poster at our locally sponsored conference RAFWE.

- I found that most people I knew (fellow graduate students, advisors, faculty, student union, etc.) did not have any familiarity with the parental leave policy at my university, let alone how to guide a graduate student through the process. Identifying the steps and personnel to communicate with felt a little like reinventing the wheel. Eventually I not only completed the process but also chronicled it and created an informational document (doc attached below for anyone who may benefit) that hopefully helps other students in the future. This process took weeks and continued beyond the birth of my child.

- June 2021: I left for parental leave and had a baby!

- September 2021: Realized that trying to leave for field work 8 weeks after having a child was simply not possible (at least for me). Canceled my field work with CCFRP.

- I signed back up with ODFW for their 2022 hook and line surveys.

- December 2021: Return from six months on parental leave