Contributed by Anne Bahde, Rare Books and History of Science Librarian

The Robert Dalton Harris, Jr. Collection of Atomic Age Ephemera is nearly ready for researcher access. Comprised of hundreds of pieces of printed ephemera produced between 1897 and 2010, this marvelous collection will serve researchers across a broad range of issues in nuclear history, covering scientific, religious, cultural, industrial, political, environmental, and other areas.

This occasion provides an opportunity to explore the particularly special genre of printed ephemera, along with its rewards and challenges. As a source type, ephemera often provides some of the richest information about a time period or topic, and can lead researchers to unique insights.

The genre has long been plagued by a problem of definition. Anne Garner, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the New York Academy of Medicine, describes the situation best: “Ephemera is a synthetic term applied inconsistently over time by historians and collection stewards…[it] has meant different things to collectors, librarians, and historians.”

Typically, the word refers to printed materials that are not commonly saved. The Ephemera Society of America’s delightfully illustrated definitions page presents a detailed history of the term, quoting Oxford Reference,

“…ephemera refers to “things that exist or are used or enjoyed for only a short time, items of collectable memorabilia typically written or printed that were originally expected to have only short-term usefulness or popularity. Recorded in English from the late 16th century as the plural of ephemeron from Greek, neuter of ephēmeros ‘lasting only a day’. The word originally denoted a plant said to last only one day, or an insect with a short lifespan, and hence was applied to a thing of short-lived interest. Current use has been influenced by plurals such as trivia and memorabilia.”

Merriam Webster is slightly more judgmental in its definition, deeming ephemera to be something “of no lasting significance.”

By definition, ephemera has its expiration date built into its creation; it is designed to be short-lived and discarded after use. Because of this deliberate temporality, ephemera that does survive its intended lifetime can often provide a sharper or closer view of a moment in time than other primary source types also surviving from that time. In this sense, ephemera is special even on the special collections spectrum.

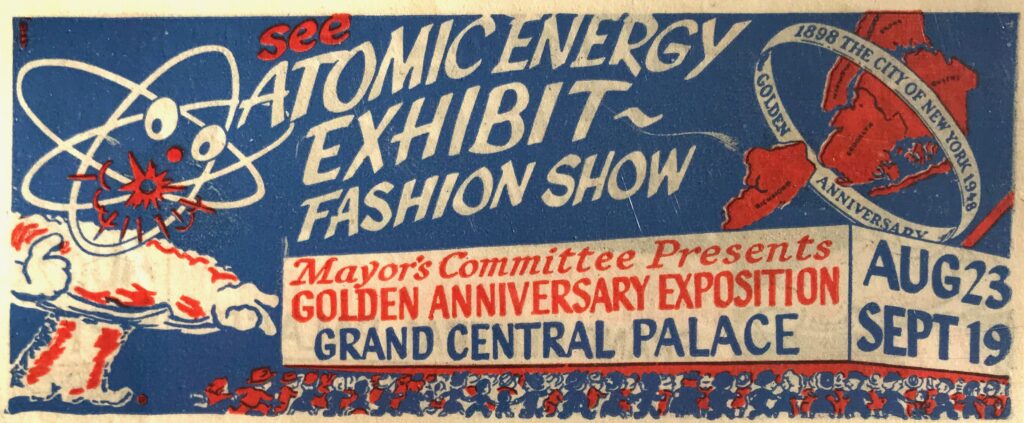

The Harris Collection has many examples of transitory ephemera designed to be short-lived or disposable. Examples of these types include brochures, calendars, comic books, envelopes, flyers, leaflets, petitions, postcards, promotional materials and advertisements, programs, stamps, and tickets.

However, the collection also contains many ephemera items that are the opposite of this definition; things specifically created to last beyond one use and/or to be kept and saved. “Something of no lasting significance” depends on who is assessing that significance, and when and why. In the Atomic Age, for example, saving the item could in fact be a matter of life or death. For example, the cards below were printed to be kept in a wallet or pocketbook in case of a nuclear weapon attack, providing a handy guide for how to save one’s life in that potentiality. (Perhaps in that sense these do imply a single use only?)

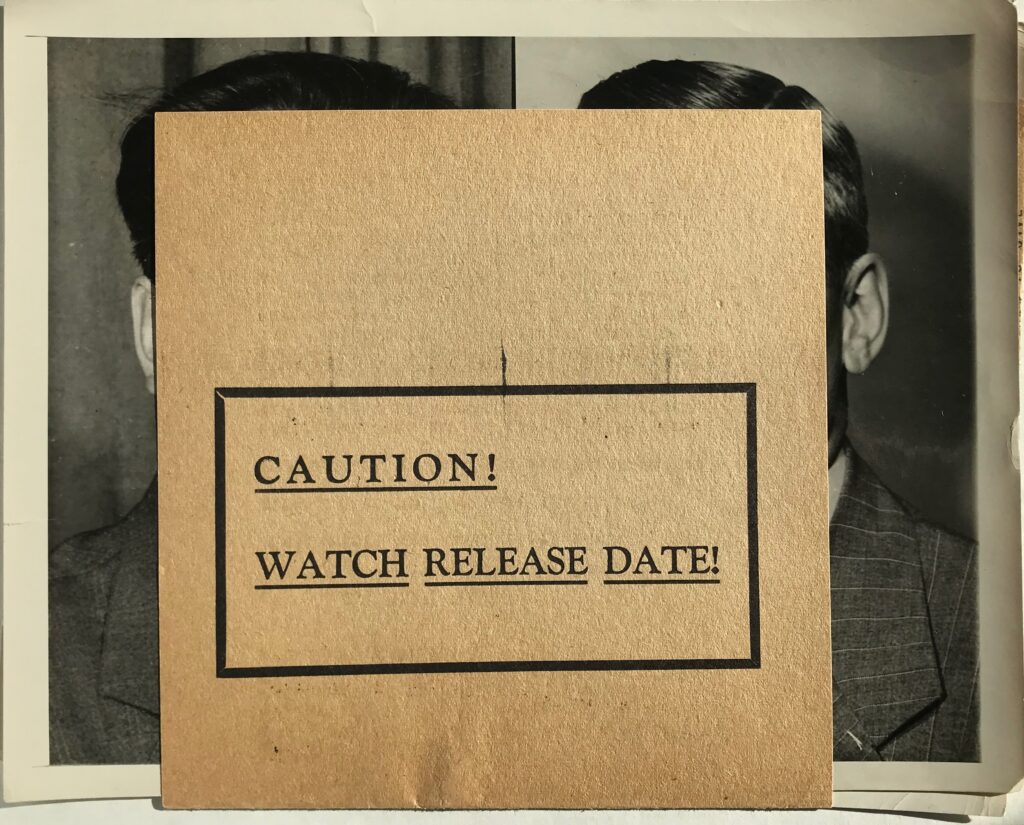

Other non-transitory material types in the collection that were meant to be kept include certificates, government documents, handbooks and manuals, maps, photographs, sheet music, and stickers. Defining an item as ephemera is sometimes dependent on its original use and context, when known. For example, today we might consider a physical photograph something to treasure and keep. But the photographs shown below were created for the purpose of press releases, which means they could be used once by a publication, then discarded if necessary (thus making their current existence more notable).

Pieces of ephemera dodge many possible deaths through time. Ephemera is generally what goes into the wastebasket when a purse or a drawer or a pocket is emptied. But at some point, some human decided that an item was worth saving. Many pieces in the Harris Collection bear physical evidence of that saving effort over time, showing careful folds, taped edges, and smoothed crumples. Perhaps it was merely chance that saved the item, safely setting it aside through a kaleidoscope of shifting human circumstances and situations.

The following five pieces from the collection illustrate the ambiguity of the term and raise provocative questions about the nature of ephemera and the lessons ephemera can teach us.

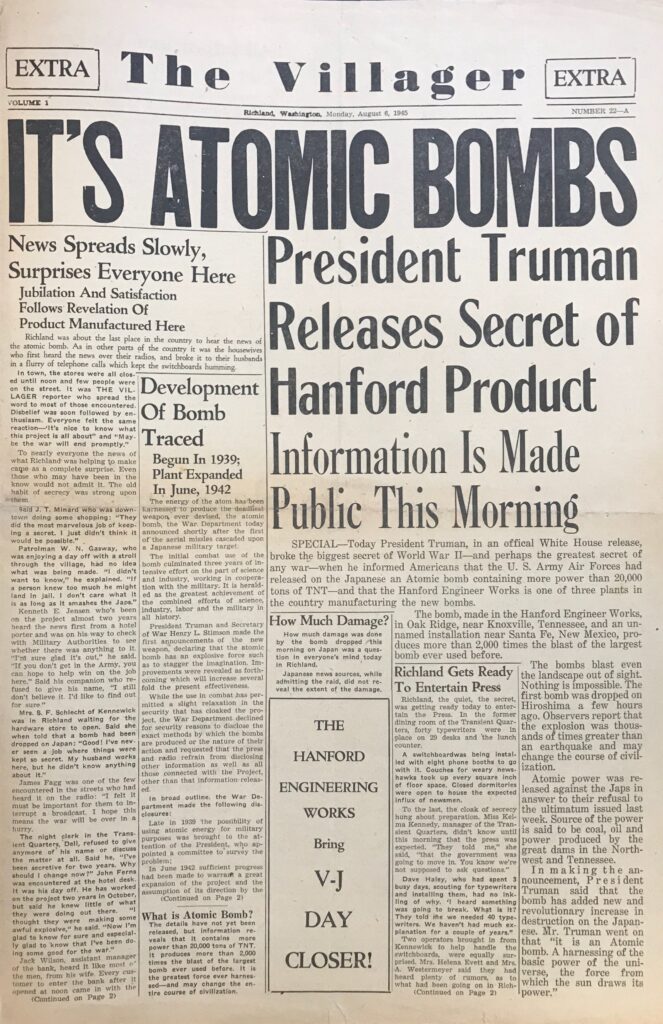

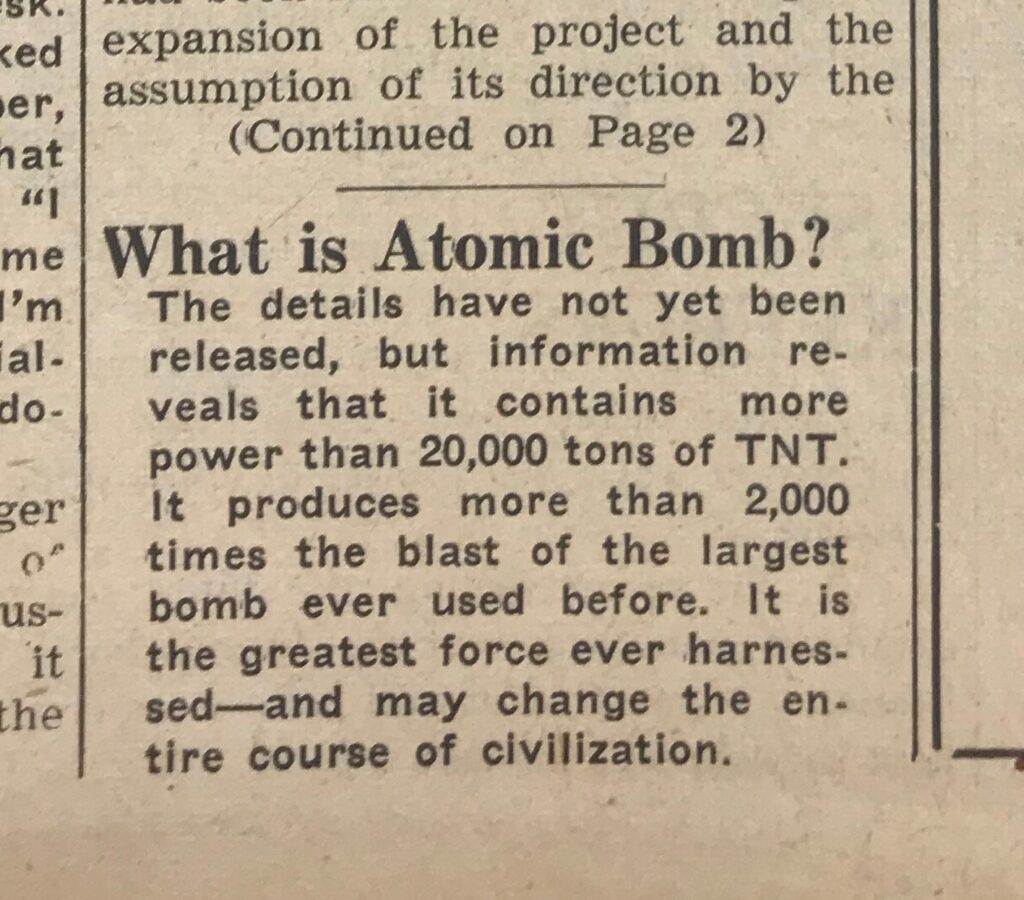

1. The Villager was the town newspaper for Richland, Washington, where the massive workforce for Hanford secretly resided. This Extra issue was produced in the hours immediately after news of the atomic bomb had been released to the world. A detail from the main story puts modern readers straight into the confusing fray of the news around town: “as in other parts of the country, it was the housewives who first heard the news over their radios, and broke it to their husbands in the flurry of telephone calls which kept the switchboards humming.”

This page also gives us a look at how tricky it must have been to be a journalist at Hanford. Upon hearing the news, the unnamed reporter for The Villager immediately set out to spread the revealed secret on the street. But this reporter had the very frustrating role of breaking news both to skeptics and to those who had been repeatedly warned about keeping secrets. Reactions ranged from disbelief, to pride, to jubilation and hopes for the war to be over soon. Several workers voiced racist hatred of the Japanese. But many of them wouldn’t talk at all, concluding that they had been told never to talk about the project, their role in it, or anything else to anyone, and therefore had nothing to say: “You know we’re not supposed to ask questions.”

This page is filled with remarkable statements that help us understand how Americans would collectively process the news of the atomic bomb. One small box in the center of the page asks “How Much Damage?” reporting that while everyone was asking the question, no true news about this fact was yet known: “Japanese news sources, while admitting the raid, did not reveal the extent of the damage.” Another small box asks “What is Atomic Bomb?” and marvels that “observers report that the explosion was thousands of times greater than an earthquake and may change the course of civilization.” This statement is repeated elsewhere on the page, suggesting the difficulty of conveying news of such magnitude to readers.

The grouping of newspapers in the Harris Collection invites comparisons across different categories to aid in teaching and learning. When grouped with other Villager issues, issues of the Oak Ridge Journal and T. E. C. Bulletin, this issue can illustrate how workers of the Manhattan Project began to understand their role in this news and how it affected the end of the war. One of them likely kept this memento of the day the secret was known, and the day their world changed forever.

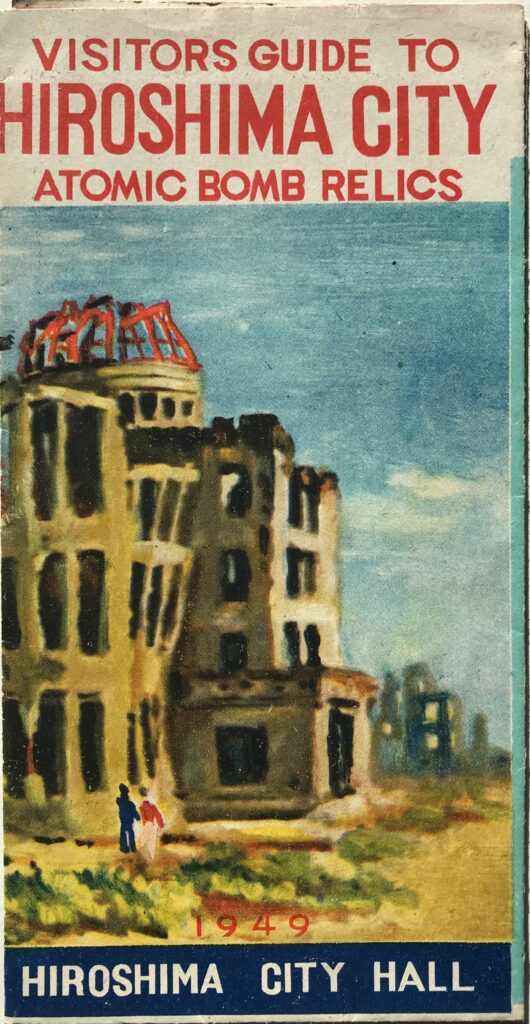

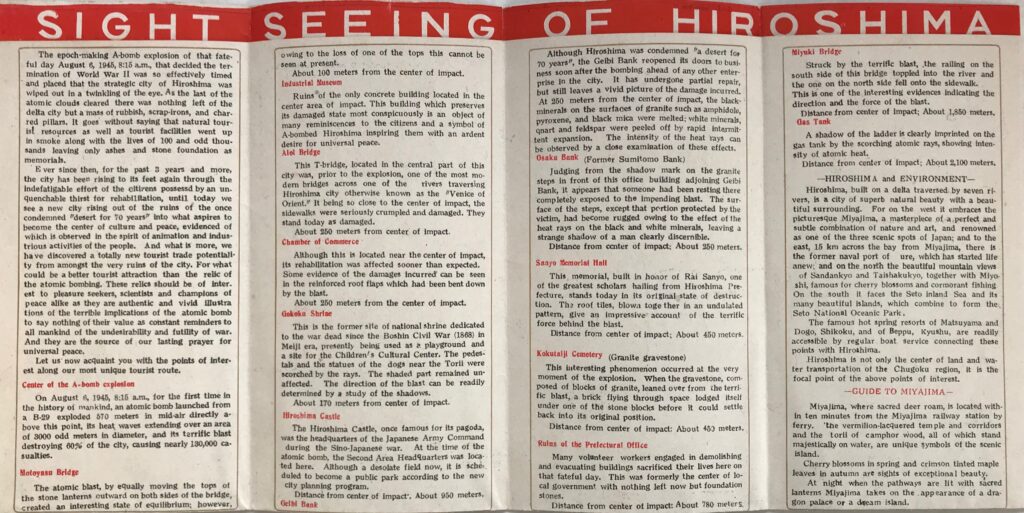

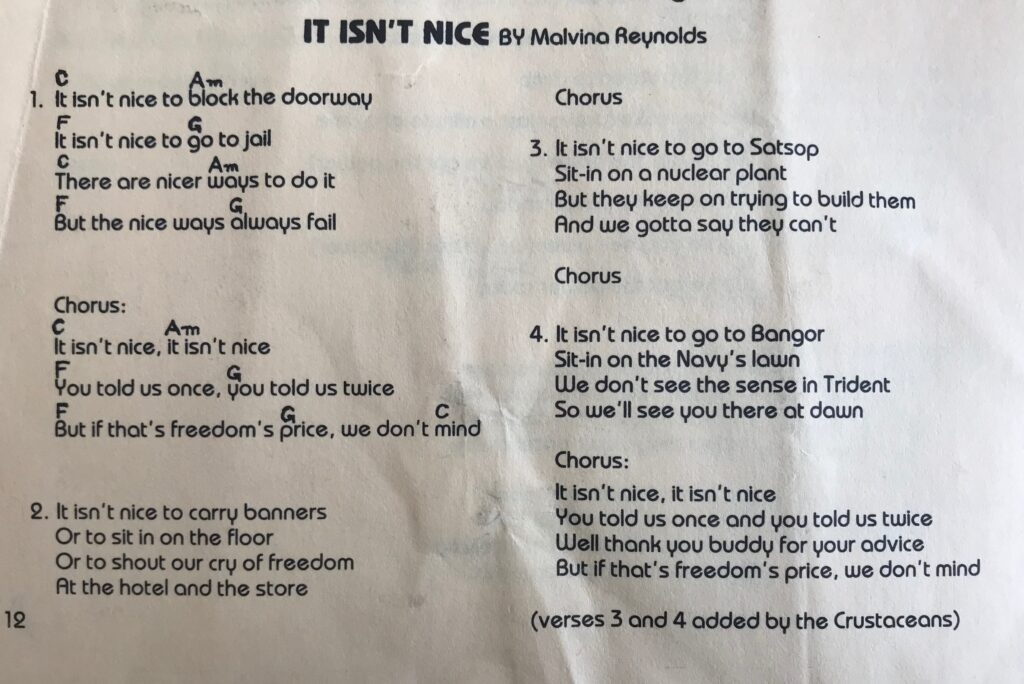

2. This astonishing pamphlet, issued by Hiroshima City Hall, was produced just four years after the first atomic bomb destroyed the city. The black and white photographs that had been seen in the press showed charred, flattened, twisted ruins where a vibrant city had once stood; but the dead grays of those photographs are replaced here by bright blues, greens, and reds. Artist “S. O.” conveyed the hope and spirit of rebirth in the city at that time with this design, and with the flock of birds soaring above the ruins. The pamphlet describes the sights of the city, encouraging visitors to “See the Progress of Peacetime Reconstruction out of the Ruins of War” via a series of tram stops.

The audience for the guide is identified as the “totally new tourist trade” for the city, made up of “pleasure seekers, scientists, and champions of peace.” (Who among these groups thought to keep this fragile pamphlet from the wastebasket?) The unattributed text inside uses precise, descriptive words to show visitors the city’s ghosts. At each site of interest, the text directs the attention of visiting scientists and ‘pleasure seekers’ towards the material evidence of the bomb, observable phenomena, and distance from the center of impact.

At the Geibi Bank, 250 meters from the center of impact, “judging from the shadow mark on the granite steps in front of this office building adjoining Geibi Bank, it appears that someone had been resting there completely exposed to the impending blast..leaving a strange shadow of a man clearly discernible.” Other entries point out similar reminders of those lost to the bomb. Away from the ruins, visitors are also encouraged to also seek sights of natural beauty at nearby Miyajima, “where cherry blossoms in spring and crimson tinted maple leaves in autumn are sights of exceptional beauty.”

Perhaps this guide was not meant to be saved. But because it was, its lessons about forgiveness, peace, and resilience become lasting and poignant. There are two other known copies of the pamphlet, just one other in the US.

Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission

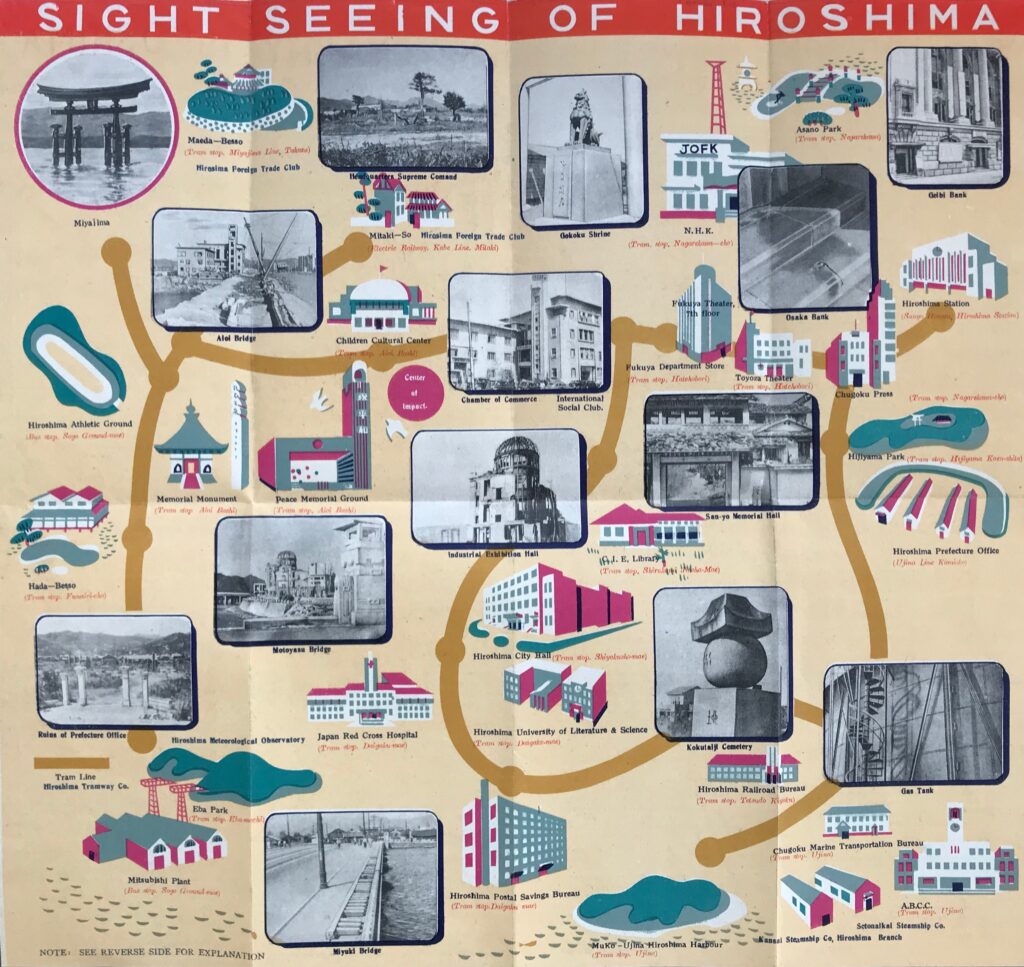

3. This stapled, slightly crumpled mimeographed booklet is a beautiful artifact of the spirit and drive of antinuclear activists in the late 1970s. Shelly & the Crustaceans was an “independent performing collective,” derived from a Northwest antinuclear activist group called the Crabshell Alliance. (The Crabshell Alliance was the West Coast’s answer to the Clamshell Alliance, an anti-nuclear group created to oppose the Seabrook Nuclear Plant in New Hampshire.) The Crabshell group was formed in early 1977 to “oppose the construction of the Satsop twin nuclear plants in southwestern Washington.” Shelly’s rallying songs are meant to be sung to familiar tunes of the day, such as “Under the Boardwalk” (re-titled to “Imminent Danger”). The core of the show seems to have been a “mini-rock-operetta complete with Mom, apple pie, a meltdown, and the lesson of Power in Union,” written for the people of Grays Harbor County where the Satsop plants were being built.

The activists were up against difficult odds. They fought against well-resourced lobbyists and developers, as well as citizen apathy and ignorance. Lyrics to songs like “It isn’t Nice” by Malvina Reynolds reflect the activists’ stalwart rejection of the traditional strictures of polite public behavior they had grown up with. The adapted lyrics to “Sixteen Tons” warn local listeners about nuclear reactors and waste, as well as potential ongoing dangers: “If the strontium don’t get you / then plutonium will.”

Ultimately the Satsop project was doomed by skyrocketing building costs and building delays, combined with a ballot measure passed by voters in 1981 that required any further additional funding for construction to be voted upon by citizens. Perhaps Shelly and her Crustaceans’ dedicated advocacy had something to do with that fate. Only one of the ‘twin’ plants was ever built, and that was permanently closed in 1999. Other printed “nuclear music” artifacts in the Harris Collection include sheet music from the early 20th century radium craze, sheet music on the atomic bomb threat from 1945, and the next baffling item below.

4. This poster was produced in 1980 (and is not a later satire as might be thought upon first encountering it). The text proclaims that “[a]cting to protect the public safety, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has issued a statement in the form of a rock & roll album” and promises “[m]usic that confronts issues.” The order form on the back proves this was an actual new wave band on an actual label called Official Records with an actual album entitled REACTOR. Besides taking issue with nuclear industries, the band tackled a wide-ranging agenda including sugar addition, fax machines, the military draft, and population growth. Quotes from Albert Einstein, Chuck Berry, and Adlai Stevenson surely enticed the potential record buyer.

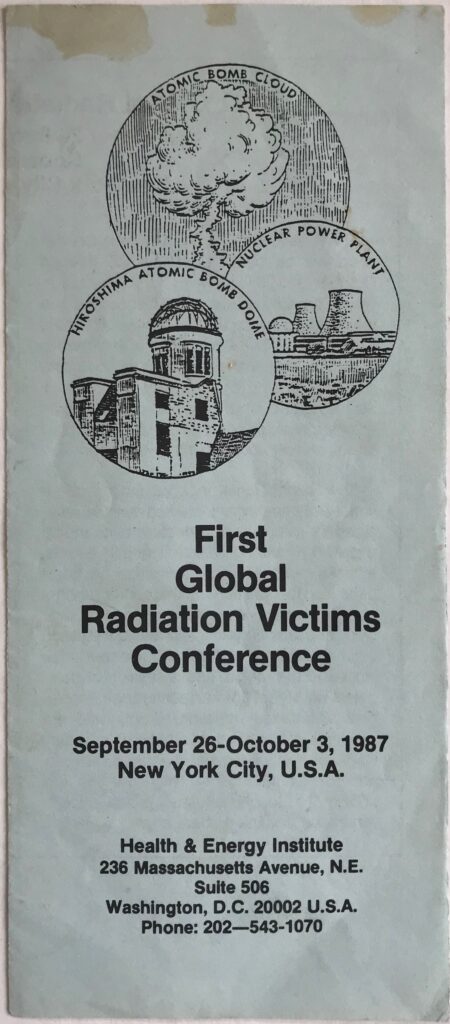

5. This beige brochure is just a folded, stained piece of paper. But even modest pieces of ephemera can tell mighty stories. The First Global Radiation Victims Conference was held at the Health and Energy Institute in New York City, and was designed to attract a wide audience of victims, their families, medical and legal experts, and activists. The organization’s broad goals include establishing and protecting the rights of all Hibakusha (a term for survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, broadened here to all victims of radiation), eliminating nuclear industries, reducing weapons, and beginning a global movement for survivors of radiation.

The back of the brochure lists other publications available from the Health and Energy Institute meant to support and inform, including a Radiation Victims Organizations Directory listing by state, as well as brochures on women and radiation, and radiation hazards on the job. Though the conference itself did not endure beyond a couple of years, the attention to radiation victims and survivors of nuclear blasts would only increase in the years to come. Publications and ephemera such as those listed in the brochure, along with the dedicated activism of the antinuclear leaders involved, brought growing awareness of victims’ plight to the world. Within a few years, Congress would pass the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, the first Downwinders lawsuit would be filed, and new activist groups and conferences would emerge.

Ephemera collections such as the Harris Collection contain rich materials to both support and inspire research. SCARC has many, many collections containing ephemera from the later 19th century to the present day. If you are looking for research inspiration or have an interest in the many forms ephemera can take, we are welcoming consultation and appointments at scarc@oregonstate.edu. The Harris Collection will be available to researchers this month – watch this space for an announcement. And next time you clean out pockets or drawers or attics, pause just for a moment before sending something on to the trash, and consider: what lessons might this teach in the future? That crumpled item may not seem “of lasting significance” at that moment, but someone years from now may thank you.