Contributed by Anne Bahde, Rare Books and History of Science Librarian

Though the pandemic has slowed progress on some projects in SCARC, staff have moved forward steadily on the work for cataloging, arranging, and describing our materials. In my case, I am working through the massive new acquisition of the Robert Dalton Harris, Jr. Collection of the Atomic Age in order to prepare it for various forms of description and access.

This collection includes three major parts. The first to be opened for research will be the Collection of Atomic Age Ephemera. This wide-ranging collection presents a thorough view of the impact of the atomic age on modern culture and society, through thousands of pieces of printed ephemera in dozens of material types, including brochures, calendars, stamps, advertisements, pamphlets, posters, and more. The second part of the Harris Collection, the archival collections, will be processed over the coming years. Currently there are 25 separate collections identified, which include compelling manuscript materials from servicemen and servicewomen, participants of the Manhattan Project, power plant engineers, uranium miners, and many others. Finally, the third part of the Harris Collection is the book collection, which includes thousands of titles covering all aspects of the Atomic Age, and for which cataloging will be ongoing.

The broad range of the Harris Collection is part of why we considered this collection to be an excellent match to OSU’s strong existing collections on nuclear history. But, this overlap also means duplication of our existing collections will occur. When potential duplicate titles are encountered, items are examined against each other in a comparative process to ensure they are true duplicates. This exercise is a necessary step – shelf space is at a premium in our holding areas, and we must ensure it is used responsibly. Most potential duplicates end up being true duplicates, which are then discarded through our surplus property protocols, or by the conditions specified by the donor.

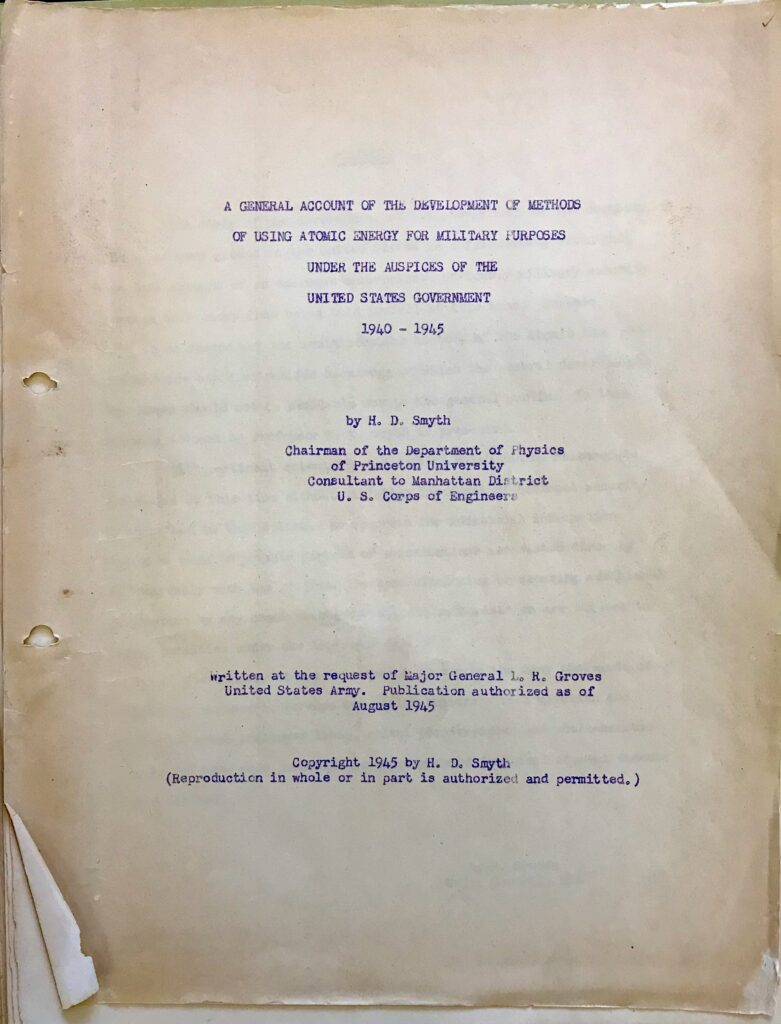

As I worked through the Harris Collection, there was one book which gave me a thrill each time I uncovered yet another duplicate copy. Whenever I spot this distinctive mustard yellow color, I become excited to meet another copy of this title. For this modest-looking volume can be considered a sort of Gutenberg Bible of the Atomic Age, in that it is the first printed document of a new era of humanity. Commonly known as the “Smyth Report” for its author, physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth, and released to the public just after the United States obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki with the first atomic bombs, A General Account of the Development of Methods of Using Atomic Energy for Military Purposes was the official government report detailing the work of the Manhattan Project. (Internet Archive).

Smyth (pronounced with a long i sound as in ‘wife’) wrote this report knowing it would be a foundational text of the new atomic age. Though the bombs were built with science known before the war, it was not widely known whether, or how, this information could be applied to create a weapon. As Smyth reflected in 1976, “it was only a question of time” as to when the dots would be connected. When leaders of the Manhattan Project knew that the atomic bomb would be a viable weapon, they also knew that the general public would need a clear and concise explanation of this new destructive force as soon as it was unleashed.

Smyth hoped his readership would be professional scientists “who can understand such things and who can explain the potentialities of atomic bombs to their fellow citizens” (Preface). Though he did not expect the whole literate public to fully understand the scientific concepts, he did expect scientists in turn to understand, explain, and engage their fellow citizens with the “potentialities.” Smyth’s task was to report and explain new information to the entire world, but he also wanted them to think beyond the words on the page to understand the consequences of the information for every citizen of the world.

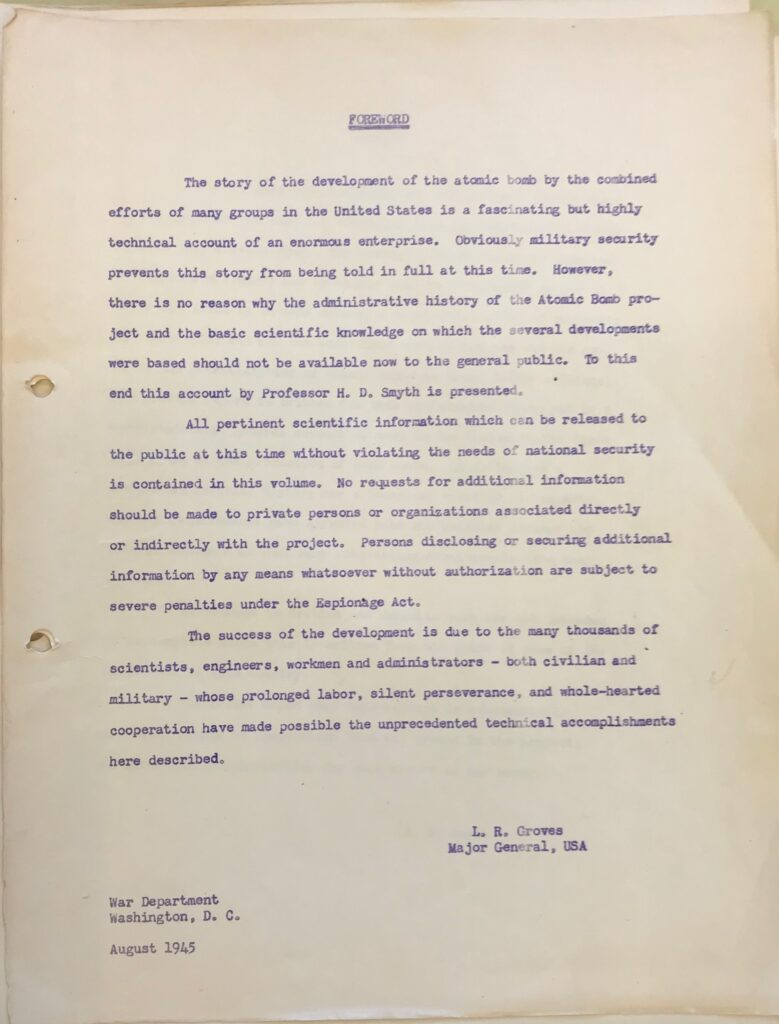

Smyth’s additional goal was to convey the administrative history of the Manhattan Project, showing how the atomic bombs came into existence. However, project leaders also required that certain information be kept hidden from the public. With General Leslie Groves’s close advisor, Richard C. Tolman, Smyth developed strict guidelines for managing and evaluating the information that would be reported in the document, ensuring that what needed to be secret would remain so in the final product.

The critical need for secrecy governed the report’s early duplication and distribution. When Smyth finished his penultimate draft in mid-July 1945, fifty copies were mimeographed in secret by project staff, then delivered by hand to selected Manhattan Project leaders under armed guard to review and return immediately. Much later, in 1976, Princeton Library Curator of Rare Books Earle E. Coleman worked with Smyth to painstakingly reconstruct the timing of various early printings and establish primacy in a detailed checklist. This first, closest-to-final version of the Smyth Report became known in Coleman’s checklist as the “mimeograph version” (Coleman 1).

(Despite the fact that no copies of the “mimeograph version” are known to exist outside of Smyth’s personal papers, later owners, collectors, dealers, and describers of this title frequently use this term “mimeograph” with wild abandon to make their copies sound more primary than they actually are.)

After final corrections were made, one thousand copies were lithoprinted in heavily secured facilities at the Adjutant General’s Office in the Pentagon. These copies were stored in a safe at the Pentagon until August 9, after the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, when President Truman made the decision to release it to the public. These copies went to members of Congress, Manhattan Project leaders and scientists, the press, and other select individuals. This version became known as the “lithoprint version” in Coleman’s checklist (Coleman 3).

(QC173 .S474 1945a)

Once the secret was out in print, the press could reproduce any and all of the information in the book without consequence, due to the unusually direct and encouraging copyright statement appearing on all printed versions: “Reproduction in whole or in part is authorized and permitted.” (However, this was tempered with a secrecy warning from General Leslie R. Groves in the Foreword: “Persons disclosing or securing additional information by any means whatsoever without authorization are subject to severe penalties under the Espionage Act.”) Smyth and Tolman’s secrecy guidelines meant that many details were missing intentionally; for example, how much fissile material was required to make a bomb and the rate at which the production plants could produce bombs.

From this point on, the report’s impact could be seen rippling out through public understanding as references to the “Smyth Report” began to appear in newspaper articles, editorials, and scientific resources in mid-August. After a scramble involving a wartime paper shortage, Princeton University Press printed and released 30,000 copies in the first trade edition (Coleman 4) on September 15, which sold out within two weeks. Another version of 10,000 copies was produced about the same time (“September 20 plus or minus five days”) by the Government Printing Office (Coleman 5).

Pauling’s Puzzling Early Versions

With the multiple duplicates added from the Harris acquisition, SCARC now has 22 copies of this matchless text, in nearly every iteration, including two very early versions in the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers. It is unknown how Linus Pauling came into possession of these copies; he reports that he got them in “summer 1945,” but does not name the source(s).

One copy, which Pauling designated “copy 2,” has been optimistically misidentified in the past as a “preliminary draft copy in mimeographed version.” However, this copy’s characteristics more closely match Coleman 2, the “ditto version.” As Coleman specifies, this copy is printed in “ditto purple” on single sheets, with a blue paper wrapper.

Coleman also notes that two identifiable typewriters were used in the production of the ditto version: one with serifs on the numerals, and one without serifs on the numerals. (Serifs are edges or strokes attached to the main stroke of a letter within a typeface. In the case of the Smyth Report, the serifs in question can be most easily spotted on the numeral 9.) Pauling’s copy 2 has exactly the pattern of alternating typewriters that Coleman specifies. The typewriter without serif numerals typed the front matter, Chapters I-IX, XIII, and Appendices 1-5. The typewriter with serifs typed chapters X-XII. Coleman also specifies that in the ditto version, paragraph 12.50 is in the middle of the page. In Pauling’s copy, however, paragraph 12.50 falls at the top of a page. This copy, therefore, seems to have elements which do not follow Coleman’s description of the ditto version.

The ditto version is also the most mysterious in terms of primacy. After interviewing those involved with producing the report, Coleman concludes, “It seems plausible…that after all the corrections had been recorded on the master copy of the mimeograph version (which had been sent to the project leaders and others), copies were made by ditto from the master copy for the final approval of General Groves and any others he might wish to review the text before lithoprinting.”

Coleman concluded that the ditto version likely precedes the lithoprint version, meaning that Pauling’s copy 2 is rare indeed, if it is indeed the ditto version.

Once bound in a three-hole punched black report cover, Pauling’s other copy is even more intriguing, and also does not clearly match any of Coleman’s described versions.

In the description for the lithoprint version (Coleman 3 and the only other early version described, besides the ditto and the unobtainable mimeograph version), Coleman notes again that the same two typewriters, one with serifs on the numerals and one without, were used in preparing the stencils for lithoprint version. He gives a careful collation of the seven copies of the lithoprint version he had examined. However, Pauling’s copy 1 is largely the opposite of this collation. (See this table for a detailed comparison). Pauling’s copy matches the Coleman 3 lithoprint description for only Chapters V, VIII, X-XI, XIII, Appendix 1, and Appendix 5, but is the reverse of what Coleman describes for all other chapters. When the title page in particular in this copy is examined closely, certain irregularities in the type can be spotted; for example, the capital M is somewhat malformed, as are several other capital letters, and overall the spacing and formation of the letters appear somewhat odd.

Further, Coleman makes no mention of the ink color of the lithoprint version, but assumedly that was because it was printed in standard black ink. This copy’s title page is printed in “ditto purple,” and continues in purple until page I-17, when it changes in the middle of the chapter to black. The ink is black until Chapter VIII when it turns again to purple for one chapter. Chapter IX is back to black which continues until the end. The black pages are printed on a heavier paper than those printed in purple and those in the ditto version, and different from the paper in the lithoprint version as well.

Coleman and Smyth acknowledge that in the copies they consulted, missing and repeated pages indicate that “the gathering of leaves was done in haste under the pressure of tight security precautions.” Neither of Pauling’s copies have repeated or missing pages, but each clearly departs from Coleman’s carefully checked bibliographical details. To fully understand how Pauling’s mysterious copies fit into the Smyth Report timeline, a complete line-by-line collation of each copy, along with a detailed comparison of other similar early copies and a full provenance investigation, would be required. For now, this secret will stay waiting for future researchers to uncover.

According to the check-out sheet attached inside the front cover, Pauling made this copy and the other available to staff in the Gates and Crellin Laboratories at Caltech beginning late September 1945. But he was strict about how long the report could be circulated, specifying that it “may be borrowed overnight. (Return next day.)” This log shows that both copies circulated for weeks among staff, well into the potential availability of the Princeton edition (suggesting perhaps that the limited Princeton first edition was more difficult to get on the West Coast).

Pauling’s lab copies were so popular that his bold, underlined directions about circulation were clearly ignored. The difference in pencilled names in the far column suggest that copies were handed around between multiple staff during one checkout period. This fascinating log is a record of how even Caltech scientists were hungry for new information, and eager to understand the force that had just changed their world. It is also a record of when certain individuals first saw the Smyth Report. William Lipscomb, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, was prompt in returning his loan. Crystallographer David Shoemaker accepted a handoff from J. Hendrickson but still turned the copy in on time. Jerry Donohue, who would go on to play a critical role in Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA, was also an early reader of this copy.

How interesting It would have been to hear this group of chemists discuss their impressions of the Smyth Report. Many chemists and engineers, including those involved in the Manhattan Project felt their important work was wholly neglected in the physics-heavy explanations. As Rebecca Schwarz has argued, the report’s silence on the critical nature of chemistry and engineering to the Project would deepen existing rifts between these fields for years to come.

In addition to Pauling’s early copies, The History of Atomic Energy Collection contains a copy of the lithoprint version signed on the title page by Smyth, along with multiple copies of the first Princeton edition, later translations, and later editions. With the additions from the Harris Collection, these make a notable set. Many of the copies were signed or inscribed by their early owners. These owners often make a point to mark the date of their acquisition, which often falls within months of its first publication. Several bear witness that Smyth’s intended audience of professional scientists were doing their part to explain and disseminate the report to citizens. One Manhattan Project engineer, Spud Spiers, proudly explained his role in the flyleaf inscription given to Alex Allan. Another copy was gifted by Manhattan Project chemist Henry A. Keirstead to his future wife Anne E. Williams in September 1945, which she then annotated extensively. Atomic energy industries were already getting a boost from powerful supporters such as Arthur Pew of the wealthy Pew family, who inscribed a copy to “a real friend of an industry which will never be second.”

But why would SCARC keep so many copies of the same book? What research value can there be, when these are just the same words in different packages? Though they may appear the same at first glance, differences and unique traits abound among these items, making them rich ground for teaching and learning. Because we have so many examples, they can be used to sharpen students’ close observation skills, or to explore now-unfamiliar methods for print and near-print production in this era such as mimeograph, ditto and lithoprinting. When paired with contemporary documents from physical and digital collections such as book reviews and newspaper articles, the Smyth Report offers important lessons in contextualization and critical source evaluation techniques.

Our group of reports can also be used to teach provenance research and the movement of information through different channels. Nearly all the items have evidence of former owners, in the form of gift inscriptions, signatures, or other elements, which means they invite further biographical research. Answering questions such as “who read this book?” and “how did readers interact with this book?” can help us understand its importance to and influence upon various audiences, as well as the flow of vital new scientific information.

Finally, because our editions are treated both archivally and as cataloged books in our collections, they present a lesson in discovery by demonstrating that the same source might appear in both the library catalog and archival finding aids, and in how to search in both environments. Within these catalog records and finding aids, there are numerous variations in historical description practices and levels of accuracy, which can teach powerful lessons on the challenges of archival search and discovery as well as the role of archivists as mediators in description and access.

Over the coming months we anticipate final release of the Robert Dalton Harris, Jr. Collection of Atomic Age Ephemera, paired with ongoing cataloging for the book collection and description of the archival collections. In future posts, we will explore some fascinating intersections of the Harris Collection with existing SCARC nuclear history collections, as well as their potential applications to research, teaching, and learning.

Bibliography/Further Reading

Smyth, H.D. “The ‘Smyth Report.’” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 37, no. 3 (1976): 173–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/26404011.

Smyth, H.D. “Publication of the Smyth Report.” International Atomic Energy Agency Bulletin 4 (1962): 28-30.

Coleman, Earle E. “The ‘Smyth Report’: A Descriptive Check List.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 37, no. 3 (1976): 201–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/26404013.

Smith, Datus C. “The Publishing History of the ‘Smyth Report.’” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 37, no. 3 (1976): 190–200. https://doi.org/10.2307/26404012.

Carter, John and Percy Muir. “The Atom Bomb.” Printing and the Mind of Man. Munchen: Karl Pressler, 1983.

Wellerstein, Alex. Restricted Data : the History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Schwartz, Rebecca Press. The Making of the History of the Atomic Bomb: Henry DeWolf Smyth and the Historiography of the Manhattan Project. Dissertation, Princeton University, 2008.

Interview with Linus Pauling about his copies

Voices of the Manhattan Project: Henry DeWolf Smyth