Contributed by Anne Bahde, Rare Books and History of Science Librarian

The start of a new academic year always carries such hopeful anticipation about the future. This is the annual moment designated to define our best academic selves, to pin due dates on the calendar, to imagine the possible achievements of the new year. In September, we collectively make the effort to throw off the limitations of the past, heave our hopes into the future, and breathe in the freshness of new potential.

Though it may seem incongruous, rare book librarians think a lot about the future. Navigating the inherent conflicts between our dual goals – preserving materials and making them accessible – takes forethought and strategy. Lately, my thoughts as a rare book librarian and archivist have been swirling with uncertainties around the future of research, academic libraries, and unique materials. How does the concept of rarity change as academic libraries continue to discard physical collections? What will special collections reading rooms look like in a year, in three years, in twenty years? How will researcher demand for special collections and archives change as we find our way in a new research reality over the next few years? How will the advancing climate disaster challenge our missions, and will we be able to adapt? With others in my profession, I am anxiously scanning the horizon for what might be coming.

Before the pandemic when we were onsite, I would take a walk in the rare book stacks when my mind started spinning with thoughts like these. I would pull something interesting off the shelf to help me interact with the past and put things in perspective. Though we are now transitioning back to more onsite work, for the past 20 months I haven’t been able to handle any of the books in our collections for more than a few minutes at a time. There is one book I have missed more than others, and I am looking forward to seeing it again.

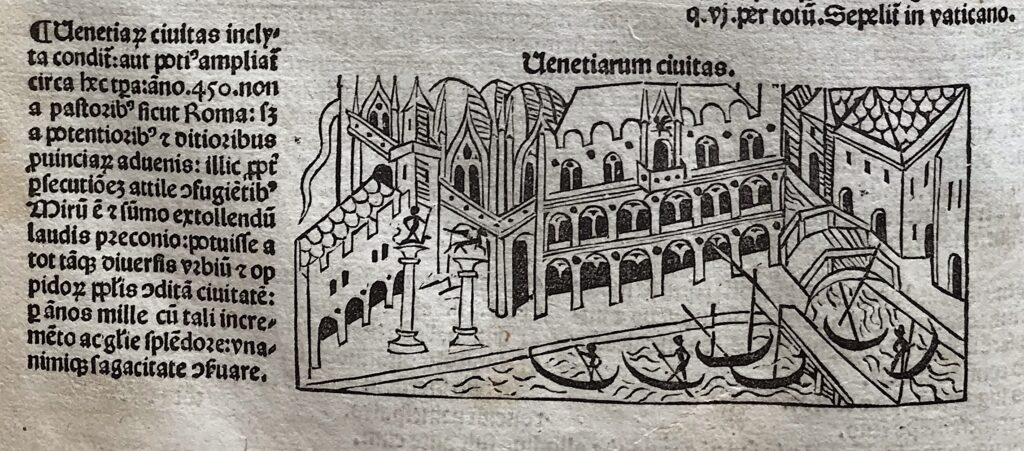

Published by Erhard Ratdolt in Venice in 1480, the Fasciculus temporum (rough translation: ‘little bundles of time’) is an illustrated timeline of historical events from biblical creation up to the year of publication. (A digitized copy of the 1481 edition can be found via Google Books here.) German Carthusian monk Werner Rolevinck compiled the first edition in 1474 from a variety of sources. His text quickly became a bestseller due to both its practical features and its engaging content, and was republished dozens of times as a popular title promising easy profit to the printers in the burgeoning European marketplace for books.

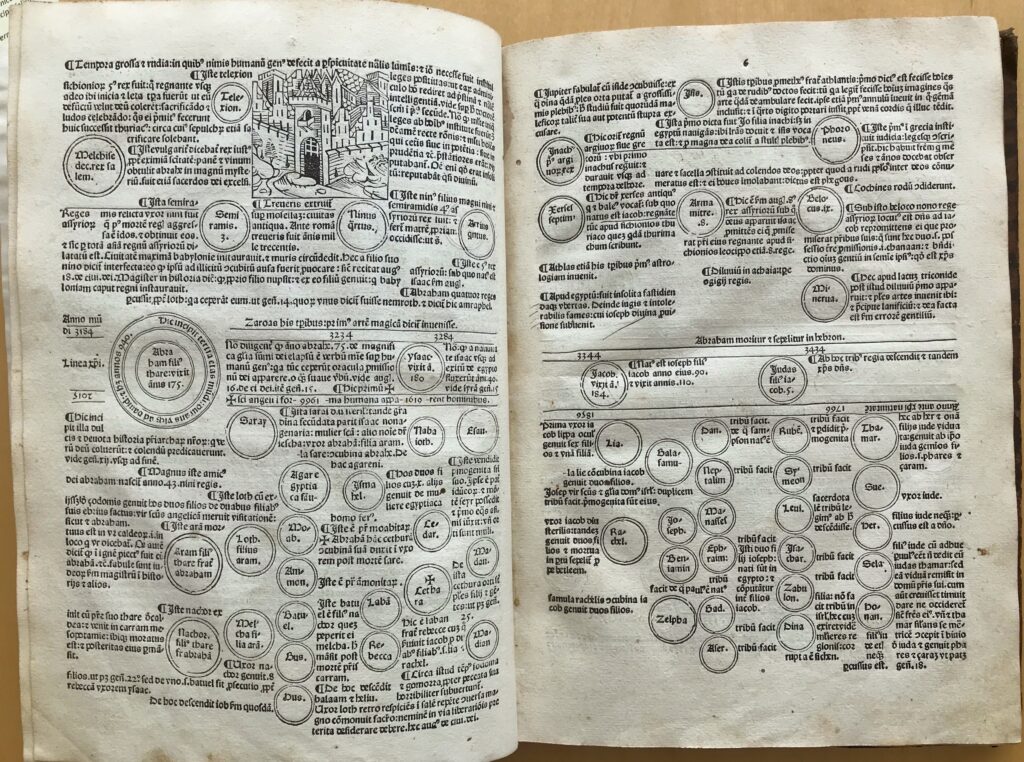

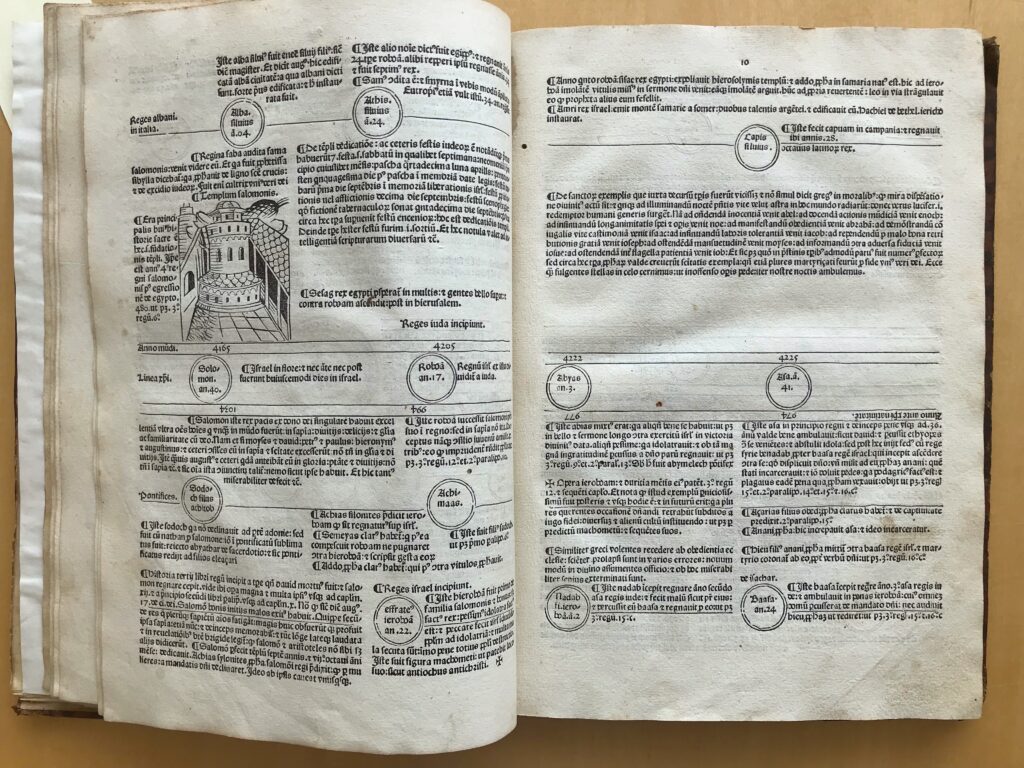

The 1480 Ratdolt edition, his first of five over the next few years, begins with an index of events sorted alphabetically by first name or title of event. In our copy, a past reader has helpfully highlighted these first letters in an earthy yellow color for easy reference. This orderly presentation moves past the solid block of an introductory page (supplied in facsimile in our copy), but quickly turns to a typographical riot of of lines, circles, text, and illustration, all mixing together to represent the notable events, people, and relationships throughout history. Ratdolt based his layout on previous manuscript and printed versions of the Fasciculus temporum, but his lively, challenging pages have a special movement in them. The reader is pulled into the flow of time and bobs from event to event in the rivers of information.

In the first part of the book, the two timelines settle into parallel tracks. The upper timeline dates the years since creation (year 1), while the lower timeline, which Ratdolt has printed upside down and in reverse chronology, counts backwards to the year of Christ’s birth, after which it resets to year 1 and turns right side up. This layout, supplemented throughout with rough woodcuts depicting cities and events, is as eye-catching and engaging now as it was meant to be in 1480.

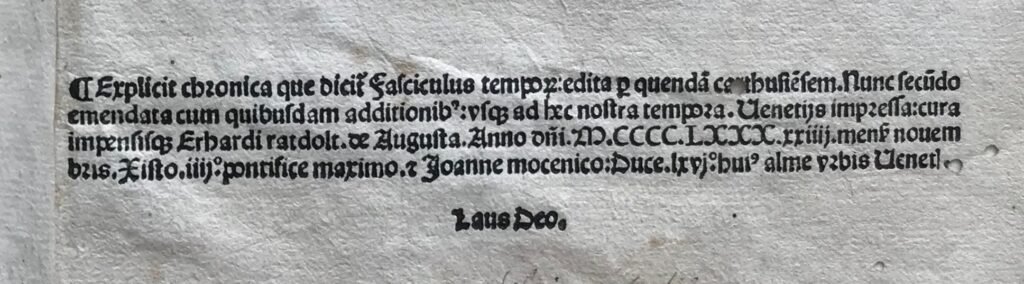

During this infancy period of the new art of printing, printers signed their work in a statement at the end of the text called the colophon. A (very) rough translation of the colophon in the Fasciculus temporum would be: “Here ends the chronicle, which is to say, a bundle of time, so issued by a certain Carthusian. Now the second edition amended with some additions to this our time. Printed in Venice at the interest and expense of Erhard Ratdolt from Augsburg in the Year of our Lord 1480 on the 24th of the month of November and Doge Giovanni Mocenico, builder of the city. Praise be to God.”

When he printed this book, Ratdolt was at the height of his creativity as a printer. He had been born at the right moment in time to be a teenager when Gutenberg introduced his printing press to Europe. Ratdolt grew into adulthood while witnessing the birth of the printed word, and in a sense he guided and shaped the new form as it evolved from that birth. He was the first printer to figure out how to print in three colors on the same page (in order to represent the phases of an eclipse); and the first to print in gold ink. He was the first to represent constellations in print. He was the first to date books in Arabic rather than Roman numerals. He created the first printer’s type specimen as a needed tool for his busy printing business. He invented my own favorite paratext, the woodcut initial. He also gets the credit for designing the first title page resembling our modern format. (Though dated, Redgrave’s article still has the most entertaining and thorough exploration of Ratdolt’s accomplishments.)

Ratdolt was also the first to figure out how to represent geometric diagrams, in his triumphant 1482 edition of Euclid’s Elementa (HathiTrust copy, OSU restricted). I have had the privilege of handling many beautiful rare books in my career, but the thrilling experience of handling the copy of his Euclid at a previous institution (San Diego State University) is among the most memorable. Quarter bound in black and green cloth, its front binding joint was very tender and it always had to be opened with care. But after that initial physical hesitation, the reader was instantly drawn into the geometric genius of the work. Page after page of labeled figures are set into and around the explanatory text, a printing invention that would change how the world learned geometry from then on. Margins meant nothing to Ratdolt, and he used the page space to the purpose he needed without the constraints of conformity. His Euclid, and indeed all his other creations, are delights of text and other page elements interacting in spirited, stimulating ways.

Ratdolt continued his contributions over a long and illustrious career. One biographer, Moritz Cantor, reports that Ratdolt “continued his business with undiminished distinction to an old age.” He died in 1528, so he even got to see his earlier work reinvented to its maximum when his new title page format finally solidified in the early 16th century (and he probably had a hand in that somewhere too). Despite this decorated career and notable impact, Ratdolt has a sadly puny Wikipedia entry. A biographical site linked there is rife with link rot. (What would this print innovator make of link rot?)

When this book was published, the familiar forms of the book that we know today were still being shaped, and that freedom from tradition is palpable on the pages. Ratdolt couldn’t know what the future of publishing would look like, but he had some ideas and ran with them, and ended up changing the way humans learned and read, now still up to our own time. His boldness, confidence, creativity, and unfettered vision still leap from his pages and inspire the reader, nearly 550 years after he had those ideas.

My favorite part of this book, though, is not among the printed pages. Our copy, in an early binding, has many indications of past reader interactions – marginalia, manicules, and other notes are scattered throughout. A musical staff is sketched next to the entry for that invention as a handy reference. One artistic early reader even added pen flourishes and decorative lines to enhance features throughout the book.

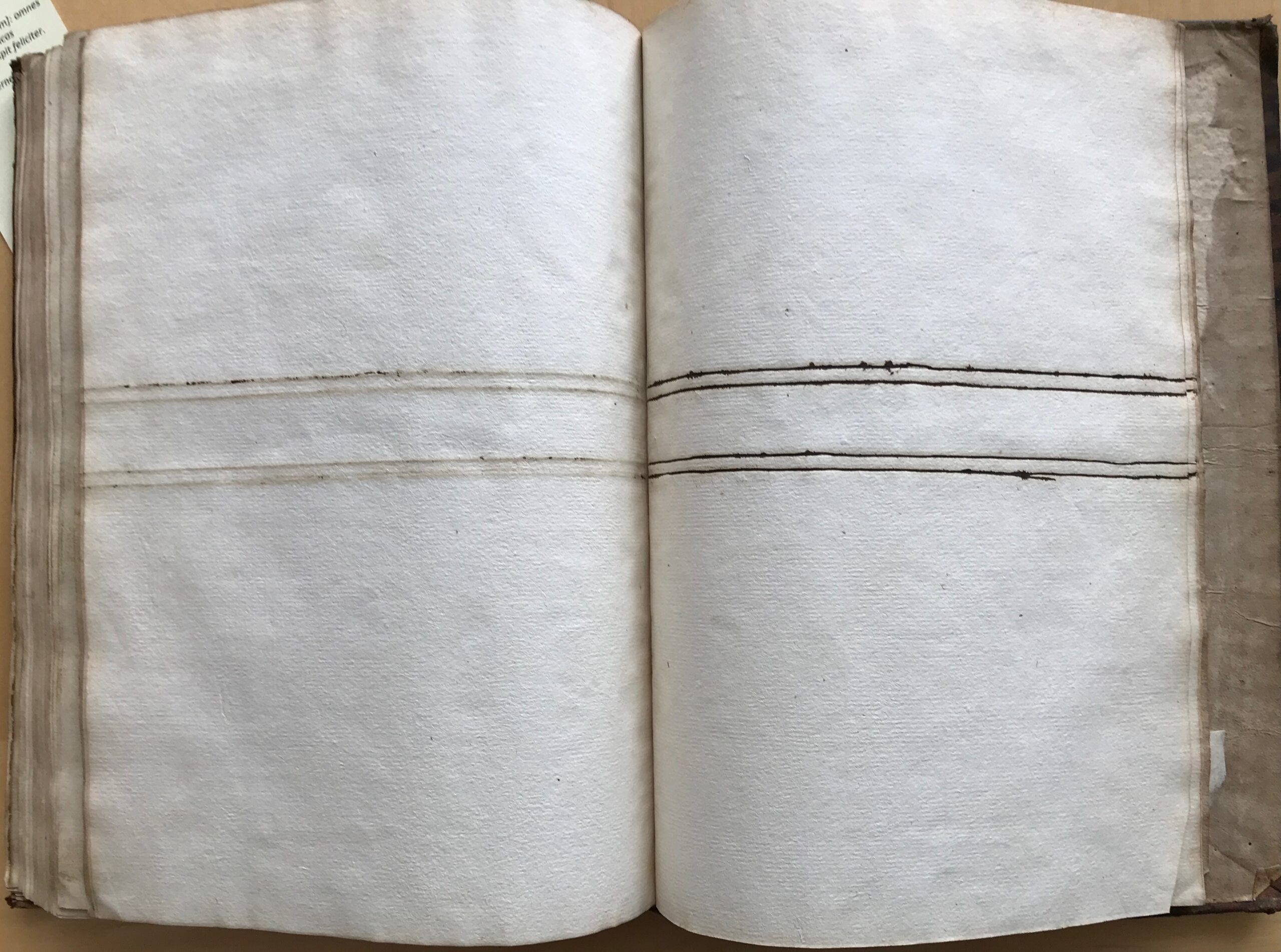

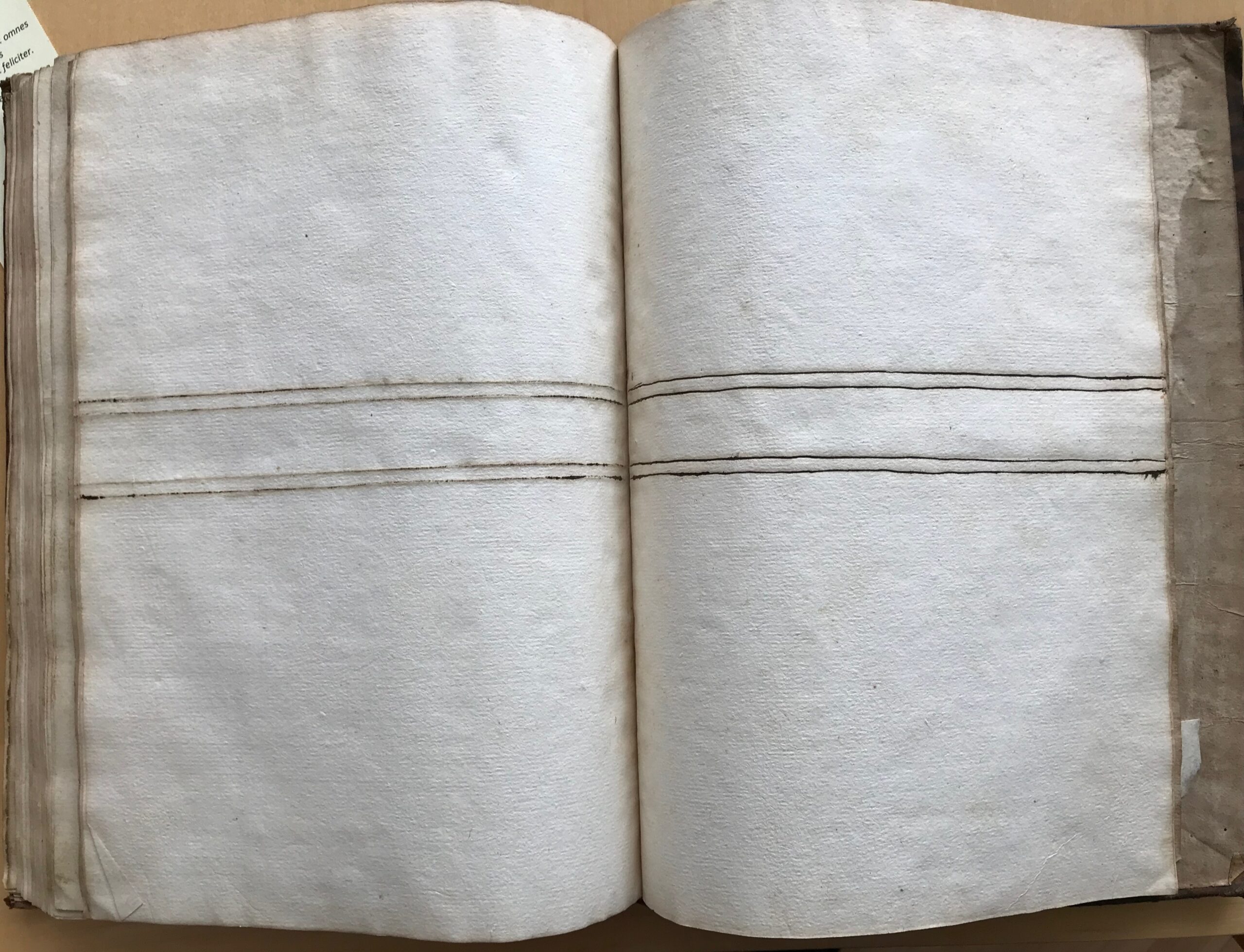

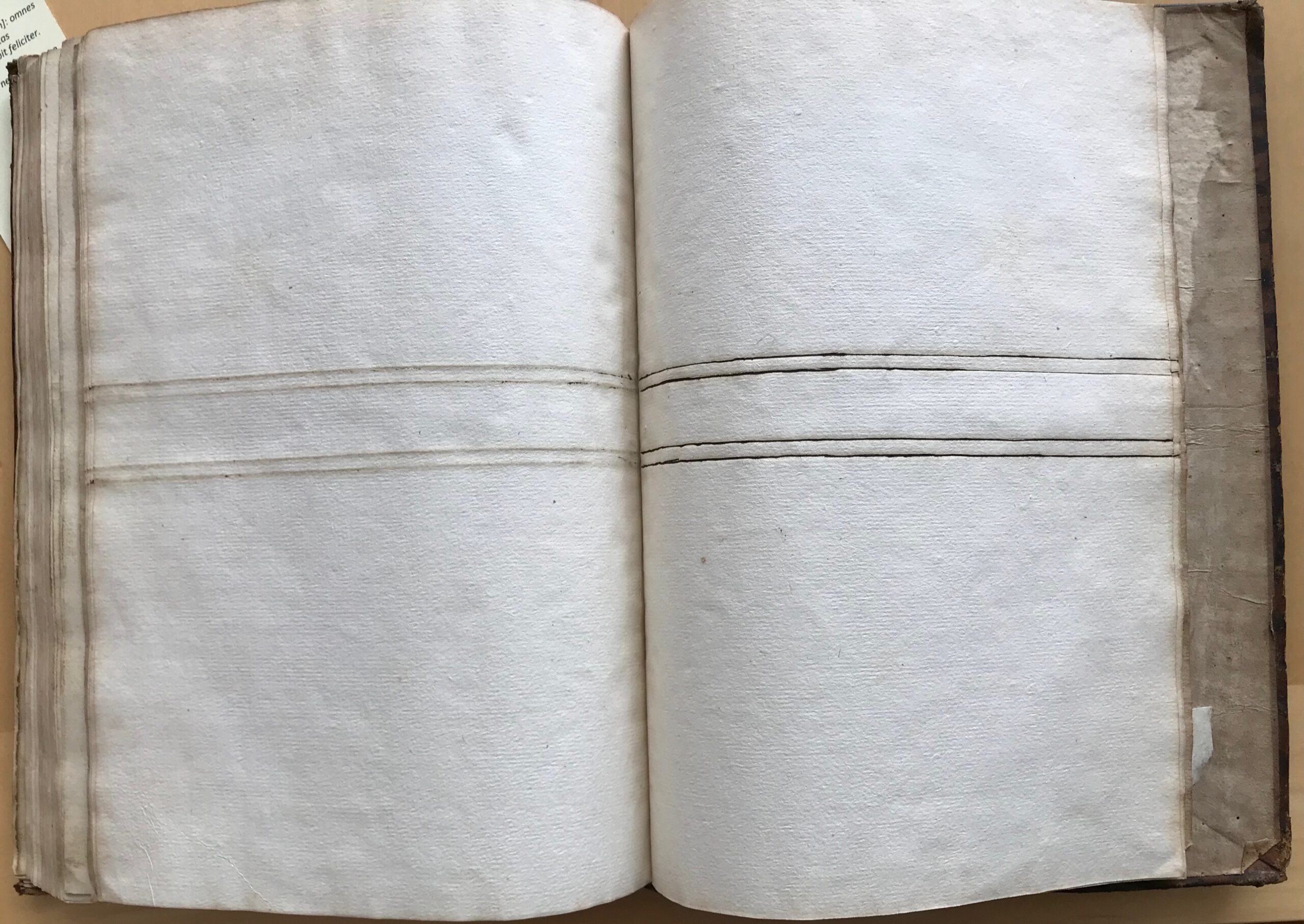

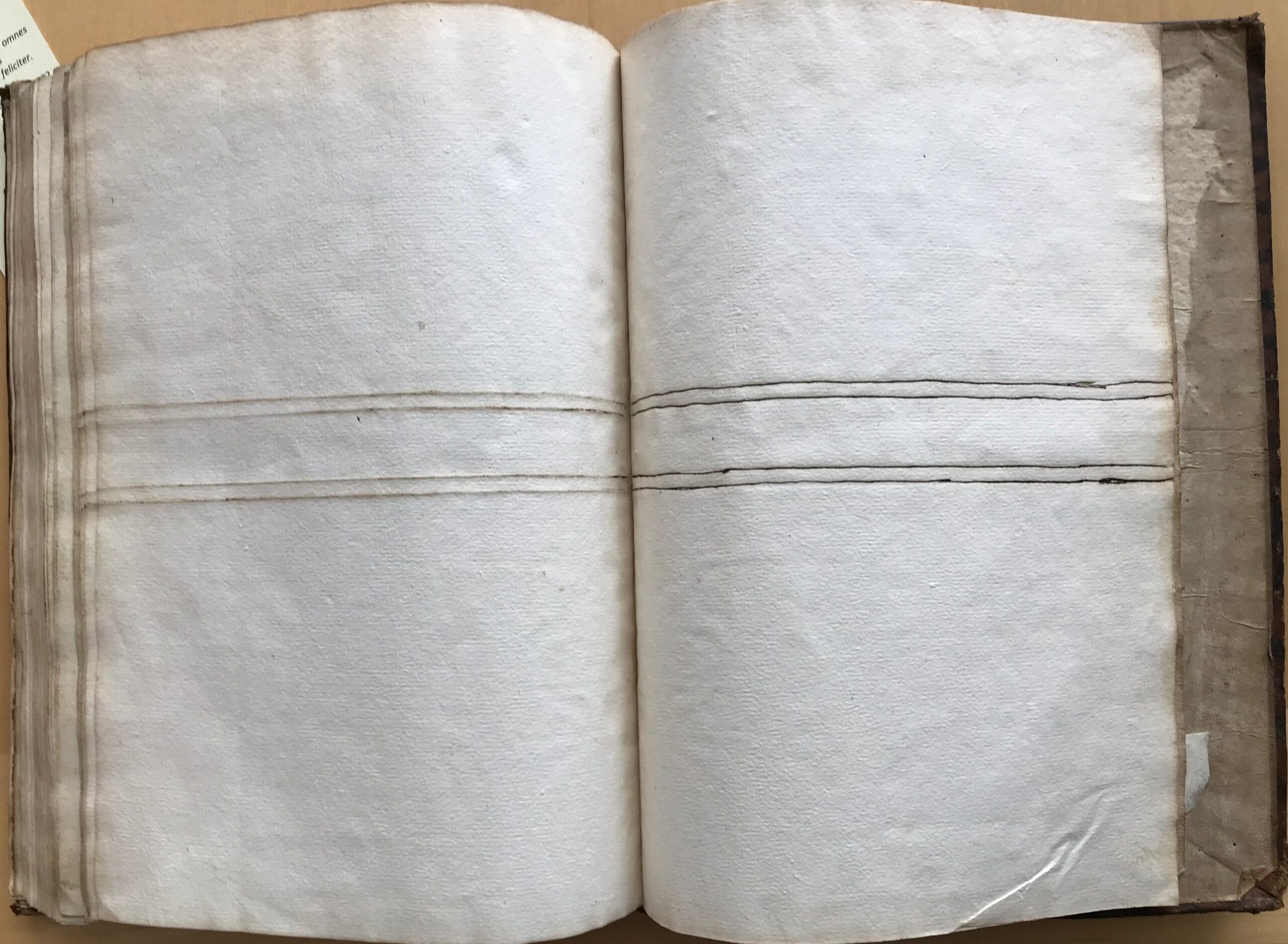

Perhaps it was the same past owner who gave this artifact its lasting power. Bound in after the very last page of the printed text are new, clean pages, neatly lined in a parallel timeline imitating Ratdolt’s design, waiting to be filled in so the reader could faithfully track events yet to happen.

These empty pages take my breath away and make my heart skip a beat, every time. Most times, my eyes tear up too. The manuscript timeline, lined in a confident hand and stretching on for a dozen pages, conveys so much readiness and anticipation. These blank lines are hope itself to me, propelled forward by the imagination of what might come next.

Living at the end of the Anthropocene, through a human time defined by uncertainty and rapid change, it is easy to get lost in prophecy or dwell on what could have been. At this moment, we are disoriented and distracted. In every other Zoom meeting, someone mutters, “time has no meaning,” as they try to remember when something did or is scheduled to happen in this blurry era.

Artifacts from the past such as this one help me live in hope, anchor me in possibility, and focus my energy on creating the future. As we begin the new year, SCARC will be back in our 5th floor reading room welcoming researchers by appointment only. If, like me, you need to feel a spark of hope and fresh anticipation, I urge you make an appointment to see this book, and to wonder: what will you be first at? What event will you number your years from? How will you manifest your talents to improve the world? What will you look back on with satisfaction in your later years? How will you live outside the margins? What are your additions to this our time, and how will you make them last? What future will you create?

Best wishes for a safe and inspiring Fall 2021.

October is Oregon Archives Month, and we will be featuring other SCARC staff favorites from our collections here on Speaking of History.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Redgrave, G. R. Erhard Ratdolt and His Work at Venice : a Paper Read before the Bibliographical Society, November 20, 1893. England: The Society, April 1894-September 1895, 1895.

Bowers, Diana. “The Physical Text is History”: Erhard Ratdolt’s Editions of Werner Rolewinck’s Fasciculus Temporum,” History of Art & Design Theses, Pratt Institute, 2015, accessed September 1, 2021, http://hadthesis.pratt.edu/items/show/62.

Bühler, Curt F. “Erhard Ratdolt’s Vanity.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 49 (1955): 186–88.

Bühler, Curt F. “The Laying of a Ghost? Observations on the 1483 Ratdolt Edition of the “Fasciculus Temporum”.” Studies in Bibliography 4 (1951): 155–59.

Josephson, Askel G.S. “Fifteenth-Century Editions of Fasciculus temporum in American Libraries.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 11 (January 1, 1917): 61-65.

Cantor, Moritz. Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Mathematik v.2: 265-68. Translated by Richard Froese. Cited by JF Ptak, “The Color Blind Geometer and the Color-Coded Euclid,” https://longstreet.typepad.com/thesciencebookstore/2008/10/the-color-blind.html.

Jeremy Norman’s ever-fascinating History of Information blog has many entries on Ratdolt’s work: https://www.historyofinformation.com/index.php?str=ratdolt