Throughout the pandemic, catalogers at OSULP have been working hard to complete projects and make progress on others. One ongoing project for the Special Collections and Archives Research Center is the creation of new catalog records for our old books.

Most libraries have an imbalance between the materials needing to be cataloged and the professional resources devoted to that work. OSULP is no different, though we are proud in SCARC that our ‘backlog’ is fairly minimal after years of progress by dedicated catalogers.

To prevent materials languishing between acquisition and cataloging, we proactively move acquisitions through descriptive processes at a steady rate. However, the backlog is still a place where mysteries can turn up, and one such mystery appeared there recently.

A short, six-page pamphlet in an unassuming binding immediately presented more questions than answers when Cataloger Vance Woods set out to create its record. Vance and History of Science Librarian Anne Bahde teamed up to find some answers about what this intriguing item was and just how it ended up in our backlog. We will explore our research over four parts presented weekly in August.

From the title page, there were a few clues to glean about what this item could be. Though neither of us read much Latin, the title of the book presented familiar Latin word roots that could at least give us indications of the time period and subject matter. For example, ‘mineral-,’ ‘corpor,’ and ‘chymia’ suggested that we were dealing with something having to do with minerals, the body, and chemistry.

A quick pass of the title through Google Translate allowed us to guess further at content and meaning in the title through a rough translation. We looked closely at the large printed mark near the bottom of the page. This spot is typically where a printer’s device would go, but in place of that identifying image, there is a decorative ornament instead. At the very bottom of the title page we typically find the publisher’s imprint, which often lists details such as the place of publication, publisher, printer, or date of publication.

We found none of those details in this section, and instead spotted Latin roots such as “sincer’ (sound, genuine, true) and ‘censur’ (judgment, opinion) here. The contemporary handwriting at the very bottom of the title page “Libavius [–ind] Paracel—” associated these apparent names to the title, along with the name Erastus which appears on the page twice. All these details began to suggest an unusual item related to the history of chemistry.

Several physical material clues intrigued us as well. The typeface and printing style suggested a printing date of the late 16th century, but confirmation of that suspicion was not found in any other elements of the item. The paper used was of a rougher nature, and the pages are now age-toned. But, no obvious clue to publication place or date could be found among the few pages.

Bindings can sometimes give hints about where or when an item was published, but in this case the binding was a simple set of brown marbled boards, probably dating to the late 19th or early 20th century given the style and condition of the binding materials. Sometimes, this type of slim, nondescript binding can suggest separation from a sammelband or nonce volume, both types of collections of pamphlets.

Though the piece lacked stab holes or other markers of prior gathering, a thin strip of discoloration does run down the length of the inner margin, suggesting that it was removed from some other binding environment at some point in the past.

The first place we both turn to when searching for items is Worldcat. Considered to be the most comprehensive catalog of materials in libraries around the world, Worldcat offers special insight when trying to track down a difficult title. A catalog record in Worldcat can tell us not only further bibliographical details about an item, but also which libraries around the world currently hold this item, thus giving a basic indiciation of distribution and rarity.

Despite search experiments with different spellings and other searching efforts, we found only one record with one holding library, the Thüringer Universitäts- und Landsbibliothek in Jena, Germany.

Deepening this line of inquiry, we followed the Libavius author entry in Worldcat, then examined each item in that list of 382 records. This is a laborious but useful Worldcat trick and can sometimes turn up some potential matches or clues for difficult-to-find items. But this effort still did not yield any further hints about this title. It slowly became clearer that we could be dealing with quite a scarce item.

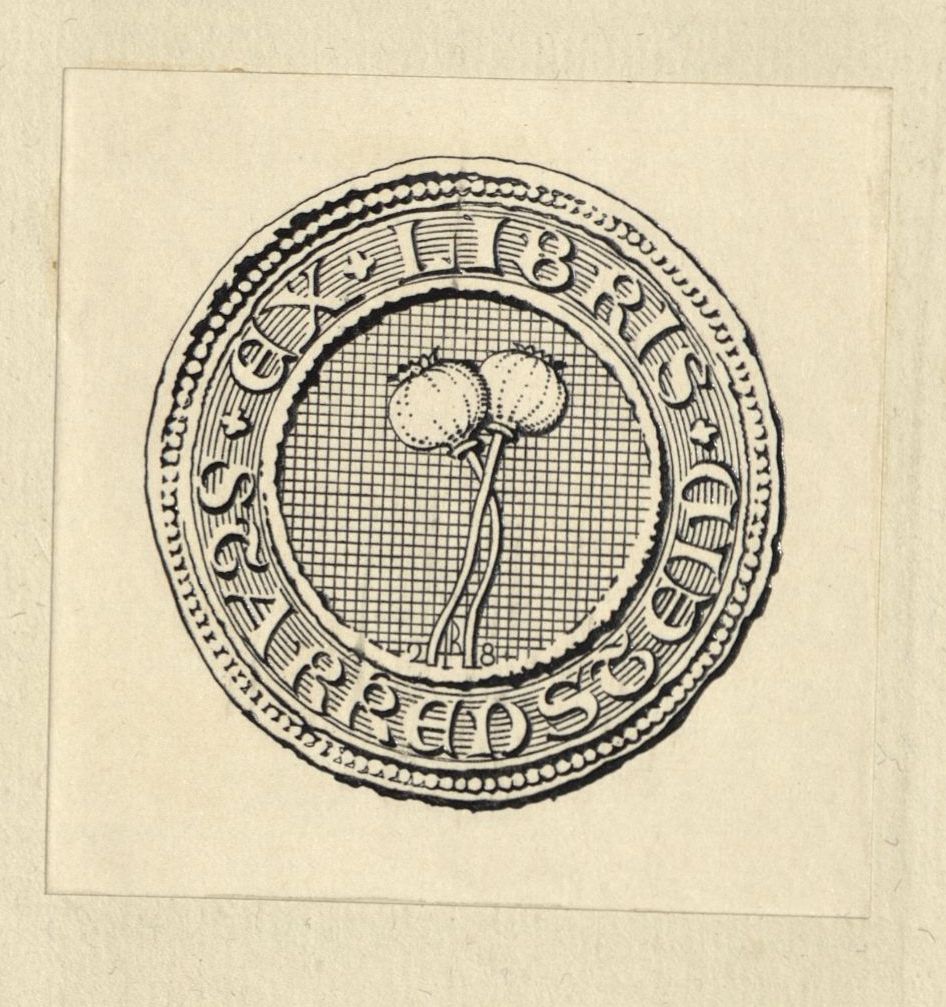

The item presented one further curious detail – the striking bookplate depicting two entwined poppy heads pasted inside the front cover. As physical signs of ownership, bookplates offer important evidence about the provenance of an item, and help later researchers track an item’s movements during its life. By searching for the name printed on the plate and looking at Google Image results, Vance discovered it was the bookplate of Emil Starkenstein, a Czech Jewish pharmacologist who was killed in the Mauthausen concentration camp in 1942. It was clear to us now that this was no ordinary book, and we began to pursue answers to the many questions the book had now invited. Part 2: Rare Books and Research follows next week.