This is Part 4 of a research exploration by Cataloger Vance Woods and History of Science/Rare Books Librarian Anne Bahde. Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.

With these details confirmed, Vance could finally prepare the catalog record for the item. The time spent on cataloging proper is by far the least time-intensive of the process; the key is to have all the pertinent information at hand so that when one begins working on the bibliographic record most of the necessary data is readily available.

As it happens, Vance was in the middle of a rare books cataloging class, and was able to incorporate some of the things he learned in the class into the record as he went. For one thing, having not worked with too many items of such early date, this was Vance’s first foray into the wonderful world of signatures (otherwise known as a collation, an indication of how the printed leaves were meant to be folded and gathered for binding). In this case, the situation was complicated by the fact that the symbol used was the Greek letter eta, which is not available in most cataloging systems, and therefore required bracketing and “transcription”: “Signatures (in Greek characters): ē4.”

Through each step of our research process to answer our initial questions “what is this item?” and “how did it come to OSU?,” we both had to call on our primary source literacy skills. Primary source literacy is defined as the set of skills needed to successfully find, understand, analyze, interpret, and use primary sources such as rare books and archives in research.

Developed in 2015-2018 by a team of 12 special collections and archives educators (of which Anne was a proud member), the SAA/ACRL-RBMS Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy show why these skills are critical for students of all ages engaging in any research involving original sources. Fluid flexing of these skills allowed us to find information quickly and efficiently through the research process for our Libavius item.

At the beginning of our process, we drew on the item to generate and refine our research questions, moving from “what is this item?” to exploring its role in the alchemical debate and the potential complications of its publication (1C). As sources were discovered and knowledge was extended, our questions took on different angles and elements, and new information was gathered at each step. We integrated that knowledge into our searching, and searched in different ways for the item in different places (1D). To place the item in a disciplinary context, we pursued secondary sources and used our knowledge of the relationships between secondary and primary sources. (1A). We examined the item and factored in material elements to understand the piece through the communication norms of the period (3A, 4E). Because we understood that the title might exist in a variety of iterations, excerpts, transcriptions, or translations through time, we searched for it across multiple platforms and adjusted our search terms as needed. (3C).

As we learned more about the item, we evaluated it critically in light of what we knew about the creator and his personal biases, as well as the original purpose behind its publication (4B). We were able to situate the source in context by applying knowledge about the time and culture in which it was created, while considering its publication history and format (4C). Our consultation of trusted expertise helped us identify and consider the reasons for gaps and contradictions in the potential publication history of the item (4D).

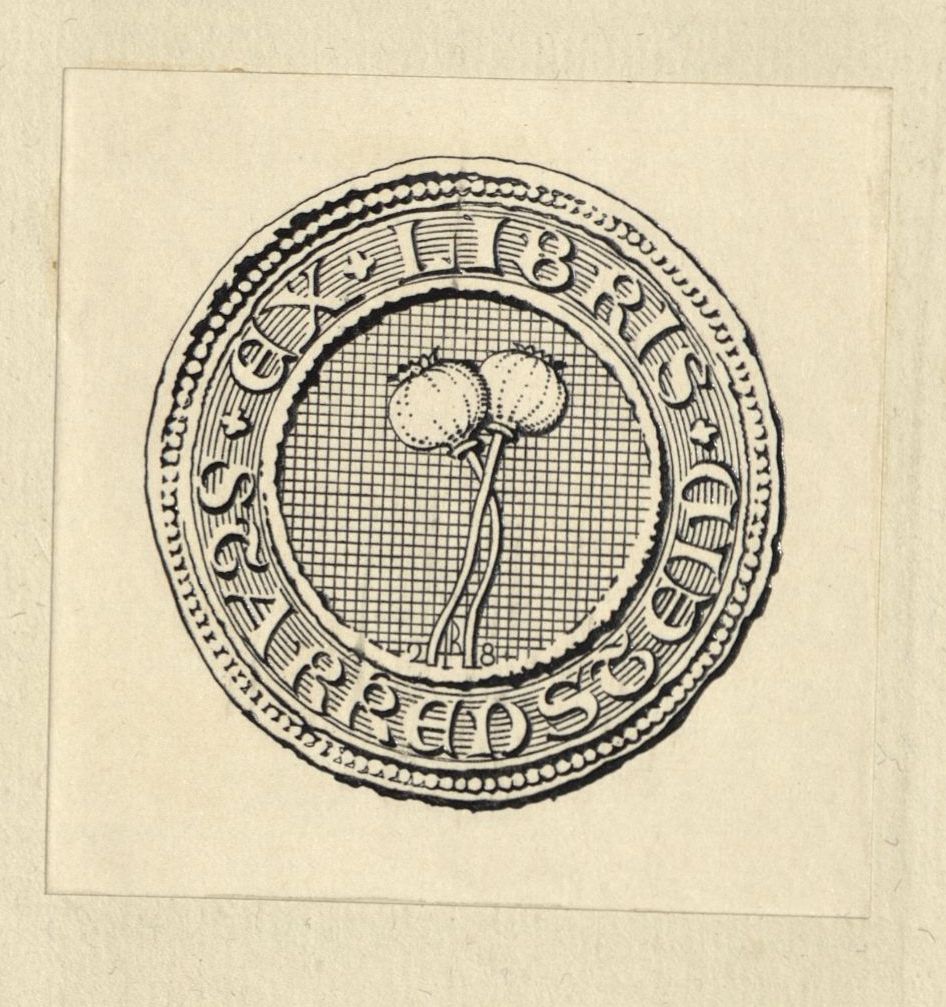

When examining its provenance and movement through the centuries, we articulated what might serve as primary sources to answer this question: purchase receipts, communication with dealers, descriptions from rare book dealers and auction records (1B). We identified possible locations of these sources in other collections using a variety of strategies and pursued those leads for more information (2A, 2B). We encountered policies that affected our access to primary sources and recognized their potential impact on our research (2E). When considering new sources, such as the auction catalog, we assessed their appropriateness for meeting our goals (4A). We met the actors in our story with historical empathy and understood how their moment in history affected their actions (4E). Finally, through our reports here, we communicated the content of sources with attention to the context of their production (3E). We examined a variety of sources to construct our research claims (5A), and practiced appropriate citation and copyright practices (5B, 5D).

With the catalog record completed, the Libavius pamphlet can take its place at last among its partners in the History of Science Rare Book Collection and join a strong concentration of rare books on the history of pharmacy and chemistry. Because we now know some of its hidden stories, the item can now function in a variety of ways to teach these primary source literacy skills. It might used to support classes or research involving early modern scientific discourse or communication, or the history of pharmaceutical use of metals, or the effects of war on the human condition, or the movement and dispersal of collections over time.

For each of these approaches, this same Libavius pamphlet could be used in class activities or research, but for each context it can hold a different teaching power, and be used to teach and learn various primary source literacy skills in partnership with other complementary sources.

The resources needed to complete quality descriptive cataloging of materials are significant, and the effort must nearly always be collective. We complete our stage of this work with questions still turning in our heads: Was the full text for our preface ever published? Might there be a record of anyone using or referencing it? Were there more prefaces printed? If so, where did they go, and if not, why not? How might this text have affected alchemical arguments of the time? Knowing that research is iterative, and that there will always be more questions than time, we place the item in the collection and wait for others to take up these paths of inquiry.

Acknowledgements

Professor Bruce Moran, University of Nevado-Reno

Brad Engelbert, Oregon State University Library and Press

Cali Vance, University of Washington Special Collections

Allee Monheim, University of Washington Special Collections

Thüringer Universitäts- und Landsbibliothek in Jena, Germany staff

Bibliography and Further Reading

Principe, Lawrence M., ed. Chymists and Chymistry: Studies in the History of Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry. Sagamore Beach, MA: Science History Publications, 2006.

Moran, Bruce T.. Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific Revolution. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Moran, Bruce T.. Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life. United Kingdom: Reaktion Books, 2019.

Moran, Bruce T.. Andreas Libavius and the Transformation of Alchemy: Separating Chemical Cultures with Polemical Fires. United States: Science History Publications/Watson Pub. International, 2007.

Debus, Allen G.. Chemistry and Medical Debate: Van Helmont to Boerhaave. United States: Science History, 2001.

Newman, William R. Atoms and Alchemy : Chymistry and the Experimental Origins of the Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

For more on u/v historical usage:

McKerrow, R. B. An Introduction to Bibliography for Literary Students. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927.

Leslie, Deborah J. and Benjamin Griffin. Transcription of Early Letter Forms in Rare Materials Cataloging. 2003. https://rbms.info/files/dcrm/dcrmb/wg2LeslieGriffin.pdf