Fast Facts

The Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) is the area in which human development and wildland areas like forests, chaparral and grasslands intersect. These areas are especially vulnerable to ignitions due to the overlap of typical wildland fire fuels such as grasses, shrubs, trees and woody debris, and human introduced fuels like trash, structures, and cars.

The WUI is growing at a rate of approximately 2 million acres/year

The WUI is dangerous for firefighters due to the mixture of fuels and the fact that wildland firefighters are not trained to fight structure fires.

40 feet between your home and the nearest large vegetation is the recommended buffer for fire risk reduction. This buffer is known as defensible space.

Executive Summary

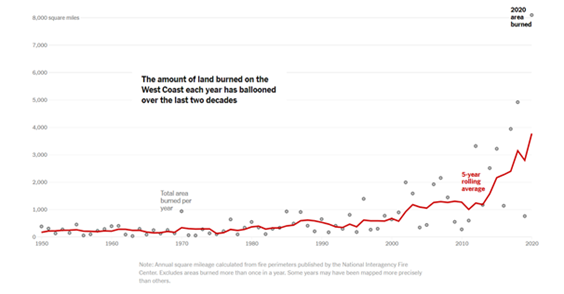

Wildfires have grown increasingly devastating over the past decade, with the summer of 2020 being the most devastating fire season on record for the West coast. Fire severity and frequency has been increasing due to a combination of two factors, climate change and a century of methodical fire suppression which has culminated in an excess of fuels in our forests. Fire exclusion and suppression on federal lands began in 1900s and has resulted in an excess of fuels in many wildland areas, especially those which used to burn on a more frequent basis, like the pine forests east of the cascades as well as oak savannas and other ecosystems which were historically maintained by frequent low severity fires. These fires removed wood, shrubs, branches, leaves and other vegetation from the area and maintained a vegetation structure with an open understory which prevented the occurrence of massive devastating fires like those which we see today. These areas were “resilient” meaning that they could bounce back from disturbances well, but by excluding fire our ecosystems are becoming increasingly unable to tolerate fire, which leads to more severe fires which take much longer to recover from Stephens et al., 2016). This lapse in resiliency is the direct result of fire exclusion and global warming.

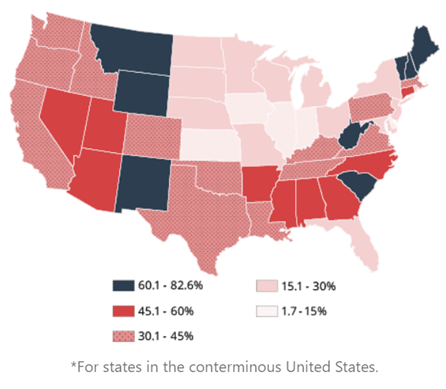

Climate change has allowed for an extension of the fire season, which historically lasted from the late summer to the early fall; it now can run from midsummer to late fall. Ignitions from humans have become increasingly common due to the increasing size of the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI), which is the area in which human development and wildland areas like forests, chaparral and grasslands intersect. These areas are especially vulnerable to ignitions due to the overlap of typical wildland fire fuels such as grasses, shrubs, trees, and woody debris and human introduced fuels like trash, structures, and cars. Wildfire fighting practices prioritize the protection of human “improvements” on the land such as homes and other structures, but wildland firefighters are neither trained nor equipped to deal with the unique fuels presented by wildfires in the WUI. This means that WUI fires are more expensive and dangerous to fight than your average wildfire, and often suppression efforts will center around homes.

More than 70,000 communities occupied by 46 million people are at risk for WUI fires and the WUI continues to grow at a rate of about 2 million acres annually (FEMA, 2021).

Significant work needs to be done on federal lands to reduce fuels and mitigate fire risks, however fire risk management should not fall solely on federal land management agencies. Residents of the WUI, where fire risk is higher and man-made fuels present risks to wildland firefighters, should be held accountable for mitigating risk on their property. The implementation of a national WUI fire risk mitigation grant program could educate and motivate WUI landowners to do their part in hazard reduction by providing funding and education about defensible space and wildland fire risks. Defensible space is a buffer created between a building and the vegetation and fuels present elsewhere on the property, such as bushes, trees, grasses, woodpiles, and propane tanks (Ready for Wildfire, 2019).

Figure 1: Acres Burned per Year Since 1950 (Graphs courtesy of the New York Times, Migliozzi et al., 2020)

Figure 2: Percent of Houses in the WUI out of Total Houses in the State* (%) (U.S. Fire Administration, 2021)

Policy Recommendations

The primary policy recommendation is to create a grant program for people living in the WUI to obtain funds for fuel reductions. These funds will be used to help individuals purchase fire resilient roofs, manage their vegetation, and lower fuels on their properties. This is similar to the existing BLM program in that the federal government is supplying the means to lower fire hazards.

This program would stand apart from the BLM’s Fuels Management and Community Fire Assistance Program because the funding would not come from the fire suppression budget, but instead a separate program. The BLM program is also aimed at communities rather than individuals, while the proposed program accepts both with proportional funding allotted. This ensures that there is sufficient funding available every year for both suppression and mitigation.

The secondary policy recommendation to create educational programs and campaigns for fire hazard awareness. These will be aimed at landowners in hazardous areas to help them manage their own properties and seek resources as needed. This includes existing programs and outside resources in addition to the proposed actions. This further informs landowners while also providing them with the opportunity to improve their own safety. Engagement and outreach programs would be established to promote safety practices, management techniques, and resource accessibility. This form of communication has been used in other forestry programs such as prescribed burn advocacy and mixed land use programs. The Smokey the Bear campaign had a significant impact on the way Americans view fire, and the same principles can be applied to fuels mitigation education (Cloughesy, 2018).

The third policy recommendation is to conduct a survey on the landscape level to assess fire risk. The survey will compile ecotype and topography data to give lower levels of government a rough estimate of the base level of risk and make management recommendations. State and Local governments can also use this data to allocate resources and assistance where it is needed most or create incentive programs to encourage participation. Surveys would be coarse grained and largely based in satellite imagery due to the scale of the project.

These policies combined would provide the means and motivation for residence of the Wildland Urban Interface to create defensible spaces and protect their homes. The initial policy recommendation to designate funding assistance to projects lowers the financial barrier to improvement. The recommendation for educational programs and surveys provided the information to prioritize, plan, and execute situationally logical projects with the aforementioned funding. The long-term effect of this is to lower likely intensity of fires in direct contact with the property, bettering health and safety. This also in greater defensible spaces in the event of a severe wildfire and could improve firefighter safety while empowering WUI residents with the ability to help protect their homes.

ACCESS OUT FULL POLICY BRIEF HERE:

Sources Cited

Bureau of Land Management (2020). BLM Fuels Management and Community Fire Assistance Program Activities. Federal Grants Wire. https://www.federalgrantswire.com/wildland-urban-interface-community-and-rural-fire-assistance.html#.YLXRf6hKjD4

Cloughesy, M., (2018). Engaging forest landowners in reducing fire danger. Oregon Research Forest Institute. https://oregonforests.org/node/604

Migliozzi, B., Reinhard, S., Popovich, N., Wallace, T., & Mccann, A. (2020). Record wildfires on the west coast are capping a Disastrous Decade. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/24/climate/fires-worst-year-california-oregon-washington.html

Radeloff, V. C., Helmers, D. P., Kramer, A., Mockrin, M., Alexandre, P. M., Bar-Massada, A., Stewart, S. I. (2018). Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 3314-3319.

Ready For Wildfire. Defensible Space. CalFire, Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.readyforwildfire.org/prepare-for-wildfire/get-ready/defensible-space/

Stephens, S. L., B. M. Collins, E. Biber, and P. Zule (2016). U.S. federal fire and forest policy: emphasizing resilience in dry forests. Ecosphere 7(11). http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.proxy.library.oregonstate.edu/10.1002/ecs2.1584

USDA Forest Service. (2015). The Rising Cost of Wildfire Operations: Effects on the Forest Service’s Non-Fire Work. United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2015-Fire-Budget-Report.pdf

U.S. Fire Administration (2021). What is the WUI? FEMA. https://www.usfa.fema.gov/wui/what-is-the-wui.html

Need closing paragraph, synthesis of problem and recc solutions