The Rocky Mountain gray wolf is a species that resides in the Northwest in Idaho, Oregon, Montana, and Washington. It can grow up to be 6 feet long and 2.5 feet tall at the shoulder. Its color can vary between black and white, and it is able to adjust to a wide variety of habitats. Although the gray wolf is a fairly adaptable and robust species, it has struggled to maintain its existence through time and human settlement.

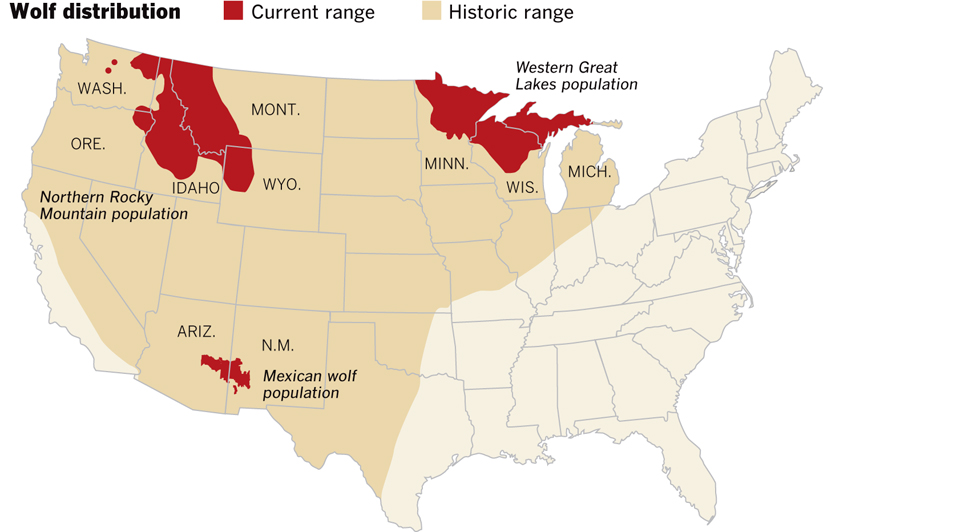

The Northern Rocky Mountain region has historically been home to the endangered gray wolf. In 1994, the known population in this area had dwindled to approximately 60 wolves in 7 packs in northwest Montana according to the Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Program 2015 Interagency Annual Report (Northern). Since 1994, there have been multiple efforts to restore the wolf populations such as the reintroduction of the species into Yellowstone National Park and Idaho. These efforts have been very successful. As of 2015, there are now thought to be over 282 packs and 1,704 wolves present in the Northern Rocky Mountain region (Northern). This shows that the population has increased dramatically due to the reintroduction and restoration efforts.

The Rocky Mountains gray wolf can live under different types of habitats. They are able to live in the arctic tundra, forest, and prairies (unknown). They also need to live in areas that contain ungulate prey like deer, elk, and bison in order to survive (Northern). They also need to live in land that contains limited travelled roads because vehicles tend to run them over. The lack of food, and the destruction of habitat by humans are two things that are ruining the habitat of these animals. They struggle to find prey because of the poaching, hunting, and trapping that humans love to do. Humans are also the ones building roads, and communities in areas where gray wolves may reside. Industrialization has become a problem that has been ruining many species, and gray wolves are no exception. We are killing their habitat for our selfish benefits, and our machines are also killing them easily. Their habitat must be protected before it is too late. They were already able to avoid full extinction, but if things stay the same, they may not be able to do that in the future.

The biggest threat to the Rocky Mountain gray wolf is humans. In 1630 the first-ever bounty on wolves was passed in the European colonies. This would be the beginning of a long tradition of people exterminating the wolf population all across America (Gray Wolf timeline). Gray wolves were nearly wiped out because of federal predator control, trapping, and poaching. In 1933 human intolerance for these wolves caused them to nearly hunt these animals to extinction in the lower 48 states. It was reported that from 2000 to 2009, 84% of wolves that died were killed by humans. This goes to show that the biggest threat when it comes to the gray wolves’ survival is humans, as they are the primary contributors to the wolf’s decrease in population. This same report also found that of those deaths, around 80% of them were intentional. This demonstrates that there is a more social aspect to this issue and that humans see the Rocky Mountain gray wolves as something to be hunted and killed instead of something to be protected. This shows that one of the greatest threats to the Rocky Mountain gray wolf is humans’ perception of them (Bruskotter).

In the lower region of the US, over five thousand gray wolves thrive due to protection of the Endangered Species Act prohibiting unregulated hunting and trapping. This has improved the recovery program and the habitat they live in. In some cases, there are populations of wolves that no longer need the protection of the Endangered Species Act because they have recovered past the point of success. One example includes the packs in the Great Lakes State of Minnesota. In order to enable the ability for recovering wolves to survive in the wild in the Rocky Mountains, they undergo pre-acclimation in the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico (US Fisheries and Wildlife Service). In the Northern Rocky Mountains, grey wolf populations are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Releasing them in that area is ideal for them to grow their population because they have more protections which eliminates threats that could hinder the recovery process.

So far the Rocky Mountain gray wolves have been making a promising comeback in many states thanks to stricter regulations against hunting. In the 1960’s it was estimated that there were only around 350 to 700 wolves left in the lower United States (Gray Wolf timeline). Thanks to new regulations the number of wolves has increased drastically and they are beginning to thrive again. It has now been estimated that after the wolves were protected under the Endangered Species Act there are around 1,782 in the lower United States as of 2014 (Gray Wolf (Canis lupus)). It was also estimated that in 2020 the Rocky Mountain gray wolf grew by 11% in Washington (Gray Wolf timeline). Despite these promising numbers, the public opinions of the Rocky Mountain gray wolves remain largely negative. Over the last 20 years, there has been a clear and concerning trend in the percent of Rocky Mountain gray wolves that were intentionally killed by people. In 2000 only 33% of wolves that were killed by people were killed intentionally. This is in vast contrast to 2020 where 82% of the wolves killed by humans were killed intentionally. The fact that a higher percent of wolves are being intentionally killed demonstrates how people’s mentality towards them is growing harsher. While numbers are on the rise they still have a long way to go and people’s feelings towards the Rocky Mountain gray wolves need to vastly change for any real progress to be made (Bruskotter).

As with any endangered species, the choice to list a species can be controversial, especially with the Rocky Mountain gray wolf. There are several distinct population groups in the Rocky Mountains that can be listed and delisted separately, making it increasingly complicated. Wolves in western North America have been deemed “recovered”, despite having a population less than 1% of their historical size, and extremely limited genetic diversity (Bergstrom et al., 2009). Another concern of citizens and law makers is that listing wolves and increasing their numbers will decimate ungulate populations, resulting in an ecosystem imbalance and lack of opportunity for hunters. Despite the fact that the ecosystem is already highly out of balance in the absence of wolves, studies have shown that wolves only account for 14-17% of elk calf mortality in the Northern Rockies, while grizzly bears and bllack bears accounted for 60% of deaths (Bergstrom et al., 2009). This proves that even in areas like the Northern Rockies that have a relatively high wolf population, mortality of deer and elk is not a significant reason not to list them as endangered. There seems to be strong evidence to support the continual listing of wolves, especially the northern Rocky Mountain populations. Along with having small populations and low genetic diversity, these animals face extreme pressure from humans, and a lack of large, suitable habitat. If continuing to be listed as endangered, these populations will be allowed to strengthen and grow for decades before they become strong enough to be delisted.

Despite making great strides towards recovery in the past few decades, Rocky Mountain gray wolves still have a long way to go in terms of reaching historical population sizes and health. Their biggest threat to recovery seems to be human influence, and pushback from people who are concerned about livestock and ungulate predation. These concerns are largely unfounded, and have been scientifically proven to not be a significant problem. Science aside, politics ultimately has the biggest influence on the status of the Rocky Mountain gray wolf. By educating people with the facts, improving habitat, genetic diversity, and prey availability for the wolves is possible.

Works Cited

Bergstrom, B. J., Vignieri, S., Sheffield, S. R., Sechrest, W., & Carlson, A. A. (2009). The northern Rocky Mountain Gray Wolf is not yet recovered. BioScience, 59(11), 991–999. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.11

Bruskotter, J. (2010, December). Are Gray Wolves Endangered in the Northern Rocky Mountains? A Role for Social Science in Listing Determinations. Retrieved November 3, 2021 from https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/60/11/941/329444.

Gray Wolf (Canis lupus). (2018, October 15). Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://www.fws.gov/midwest/wolf/aboutwolves/wolfpopus.htm

Gray Wolf. NatureMapping. (n.d.). Retrieved October 31, 2021, from http://naturemappingfoundation.org/natmap/facts/gray_wolf_k6.html.

Gray Wolf timeline: International wolf center. International Wolf Center | Teaching the World about Wolves. (2020, October 29). Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://wolf.org/gray-wolf-timeline/.

Northern Rocky mountain wolf recovery program 2015 … – FWS. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/es/species/mammals/wolf/2016/FINAL_NRM%20summary%20-%202015.pdf.

Unknown. (n.d.). Natural HIstory. Natural history. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/mammals/northern_Rocky_Mountains_gray_wolf/natural_history.html.

US Fisheries and Wildlife Service. “U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wolf Recovery under the … – FWS.” Wolf Recovery Under the Endangered Species Act, Feb. 2007, https://www.fws.gov/home/feature/2007/gray_wolf_factsheet-region2-rev.pdf.

Image Links

https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.biologicaldiversity.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2Fspecies%2Fmammals%2FGrayWolf_USFWS_FPWC_2_HIGHRES-scr.jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.biologicaldiversity.org%2Fspecies%2Fmammals%2Fnorthern_Rocky_Mountains_gray_wolf%2Findex.html&tbnid=iQRv4zYgBijX7M&vet=12ahUKEwjBp6j32_3zAhWLkp4KHezjAZkQMygAegUIARC8AQ..i&docid=tupApNQhWpR5-M&w=570&h=330&q=rocky%20mountain%20gray%20wolf&ved=2ahUKEwjBp6j32_3zAhWLkp4KHezjAZkQMygAegUIARC8AQ

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fgraphics.latimes.com%2Ftowergraphic-la-me-wolves%2F&psig=AOvVaw0-9itzNyrpMjWGdcdjrVnN&ust=1636081610158000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAsQjRxqFwoTCMDWxIzd_fMCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fupload.wikimedia.org%2Fwikipedia%2Fcommons%2F0%2F06%2FNorthern_Rocky_Mountains_wolf.jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fen.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FNorthern_Rocky_Mountain_wolf&tbnid=5SHwVNSdG0HbqM&vet=12ahUKEwi9mYK53f3zAhUQm54KHRXOB5sQMygAegUIARCsAQ..i&docid=1uz2GUxRocjMbM&w=1024&h=684&q=rocky%20mountain%20wolf%20habitat&ved=2ahUKEwi9mYK53f3zAhUQm54KHRXOB5sQMygAegUIARCsAQ

https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pbs.org%2Fwnet%2Fnature%2Ffiles%2F2008%2F11%2F610_lobo_wolf-wars.jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pbs.org%2Fwnet%2Fnature%2Fthe-wolf-that-changed-america-wolf-wars-americas-campaign-to-eradicate-the-wolf%2F4312%2F&tbnid=9OdU7mMCNYb3jM&vet=12ahUKEwj5_8703f3zAhWUjZ4KHU-PCdMQMygAegUIARCrAQ..i&docid=NLasikfcs5RtdM&w=610&h=370&q=wolf%20hunting%201900s&ved=2ahUKEwj5_8703f3zAhWUjZ4KHU-PCdMQMygAegUIARCrAQ

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.5280.com%2F2020%2F10%2Fwhat-does-delisting-the-gray-wolf-mean-for-colorado%2F&psig=AOvVaw1s0o99Iea05yqT-xBMsxmD&ust=1636081887033000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAsQjRxqFwoTCJi19pDe_fMCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.npr.org%2F2020%2F10%2F29%2F929095979%2Fgray-wolves-to-be-removed-from-endangered-species-list&psig=AOvVaw1RZFItRCV_qVRYxK6rrRtf&ust=1636081972894000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAsQjRxqFwoTCLDts7ve_fMCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAJ

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.yellowstonepark.com%2Fthings-to-do%2Fwildlife%2Fgrizzly-bear-vs-wolves%2F&psig=AOvVaw1RoDjm1-jPxR5_xOlXCBB4&ust=1636082065759000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAsQjRxqFwoTCNiJuOje_fMCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.