By Lisa Hildebrand, MSc student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Marine Mammal Institute, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Fall has arrived in the Pacific Northwest. For humans, it means packing away the shorts and sandals, and getting the boots, raincoats and firewood ready. For gray whales, it means gulping down the last meal of zooplankton they will eat for several months and commencing the journey to warmer waters and sunnier skies in Mexico where they will spend the winter fasting, calving, and nursing. While the GEMM Lab may still squeeze in a day or two of field work this week, we are slowly wrapping up the 2020 field season as conditions get rougher and our beloved gray whales gradually depart our waters. This year marked the 6th year of data collection for both of our gray whale projects: the Newport project that investigates the impacts of multiple stressors on gray whale ecology and health, and the Port Orford project that explores fine-scale foraging ecology of gray whales and their zooplankton prey. Since it will be several months before the GEMM Lab heads back out onto the water again, I thought I would summarize our two field seasons, share some highlights, and muse about the drivers of our observations this summer.

Summaries

Our RHIB Ruby zipped around the central and southern Oregon coast on 33 different days. The summer started slow, with several days of field work where we encountered no whales despite surveying our entire study region. Our encounters picked up towards the end of June and by the end of the summer we totaled 107 sightings, encountering 46 unique individuals, 36 of which were resightings of known individuals we have identified in previous years. Our Newport star of the summer was Solé, a female gray whale we have seen every year since 2015, and we also saw many of our other regulars including Casper, Rafael, Spray, Bit, and Heart. None of these whales shone as bright as Solé though. We flew the drone over her 8 times and collected 7 fecal samples (one of which was the biggest whale fecal sample I have ever seen!). In total, we collected 30 fecal samples and flew the drone 88 times. These data will allow us to continue measuring body condition and hormone levels of Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) gray whales that use the Oregon coast.

Our tandem research kayak Robustus may not be as zippy as Ruby (it is powered by human muscle rather than a powerful outboard engine after all), but it certainly continues to be a trusty vessel for the Port Orford team. The Port Orford research team, named the Theyodelers this year, collected 181 zooplankton samples and conducted 180 GoPro drops during the month of August from Robustus. Despite the many samples collected, the size of our prey samples remained relatively small throughout the whole season compared to previous years. The cliff team surveyed for a total of 117 hours, of which 15 were spent tracking whales with the theodolite and resulted in 40 different tracklines of whale movements. The whale situation in Port Orford was similar to the pattern of whale sightings in Newport, with low whale sightings at the start of the field season. Luckily, by the start of August (which marked the start of data collection for the Theyodelers), the number of whales using the Port Orford area, especially the two study sites, Mill Rocks & Tichenor Cove, had increased. Of the whales that came close enough to shore for us to identify using photo-id, we tracked 5 unique individuals, 3 of which we also saw in Newport this year. The Port Orford star of the summer was Smudge, with his tracklines making up a quarter of all of our tracklines collected. Smudge is also the whale we sighted most often last year in Port Orford.

Highlights

Many of you may be familiar with the whale Scarlett (formally known as Scarback). Scarlett is a female, at least 24 years old (she was first documented in the PCFG range in 1996), who is well-known (and easily identified) by the large concave injury on her back that is covered in whale lice, or cyamids. No one knows for certain how Scarlett sustained this injury (though there are stories), however what we do know is that it has not prevented this female from reproducing and successfully raising several calves over her lifetime. The GEMM Lab last saw Scarlett with a calf (which we named Brown) in 2016. Since Scarlett is such a famous whale with a unique history, it shouldn’t be a surprise that one of our highlights this summer is the fact that Scarlett showed up with a new calf! In keeping with a “shades of red” theme, Leigh came up with the name Rose for the new calf. In July, the mom-calf pair put on quite a cute performance, with Rose rising up on Scarlett’s back, giving the team a glimpse of its face. The Scarlett-Rose highlight doesn’t end there though. Just last week, we had a very brief encounter in choppy, swelly waters with a small whale. The whale surfaced just twice allowing us to capture photo-id images, and as we were looking around to see where it would come up a third time, it suddenly breached approximately 20 m from the boat. Lo-and-behold, after comparing our photos of the whale to our catalogue, we realized that this elusive, breaching whale was Rose! I am excited to see whether Rose will return to the Oregon coast next summer and become a PCFG regular just like her mom.

The highlight of the field season in Port Orford is the trial, failures and small successes of a new element to the project. There is still a lot that we do not know and understand about PCFG gray whales. One such thing is the way in which gray whales maneuver their large bodies in shallow rocky habitats, often riddled with kelp, and how exactly they capture their zooplankton prey in these environments. Using drones has certainly helped bring some light into this darkness and has led to the documentation of many novel foraging behaviors (Torres et al. 2018). However, the view from above is unable to provide the fine-scale interactions between whales, kelp, reefs, and zooplankton. Instead, we must somehow find a way to watch the whales underwater. Enter CamDo. CamDo is a technology company that designs specialty products to allow for GoPro cameras to be used for time-lapsed recordings over long periods of time in harsh environmental conditions. One of their products is a housing specifically designed for long-term filming underwater – exactly what we need! The journey was not as easy as simply purchasing the housing. We also needed to build a lander for the housing to sit on (thankfully our very own Todd Chandler designed and built something for us), and coordinate with divers and a vessel to deploy and retrieve the set-up, as well as undertake weekly battery and SD cards swaps (thankfully Dave Lacey of South Coast Tours and a very generous group of divers* donated their time and resources to make this happen). We unfortunately had some technological difficulties and bad visibility for the first 4 weeks (precisely why this CamDo effort was a pilot season this year), however we had some small success in the last 2 weeks of deployment that give us hope for the future. The camera recorded a lot of things: thick layers of mysids, countless rockfish and lingcod, several swimming and foraging murres, a handful of harbor seals, and two encounters of the species we were hoping to film – gray whales! While the footage is not the ‘money shot’ we are hoping to film (aka, a headstanding gray whale eating zooplankton right in front of the camera), the fact that we captured gray whales in the first place has showed us that this set-up is a promising investment of time, money and effort that will hopefully deliver next year.

Musings

You may have picked up on the fact that we had slow starts to our field seasons in both Newport and Port Orford. Furthermore, while the number of whale sightings did increase in both locations throughout the field seasons, the number of sightings and whales per day were lower than they have been in previous years. For example, in 2018, we identified 15 different individuals in the month of August in Port Orford (compared to just 5 this year). In 2019, 63 unique whales were seen in Newport (compared to 46 this year). Interestingly, we had a greater diversity of encountered individuals at the start and end of the season in Newport, with a relatively small number of different individuals in July and August. While I cannot provide a definitive reason (or reasons) as to why patterns were observed (we will need to analyze several years of our data to try and understand why), I have some hypotheses I wish to share with you.

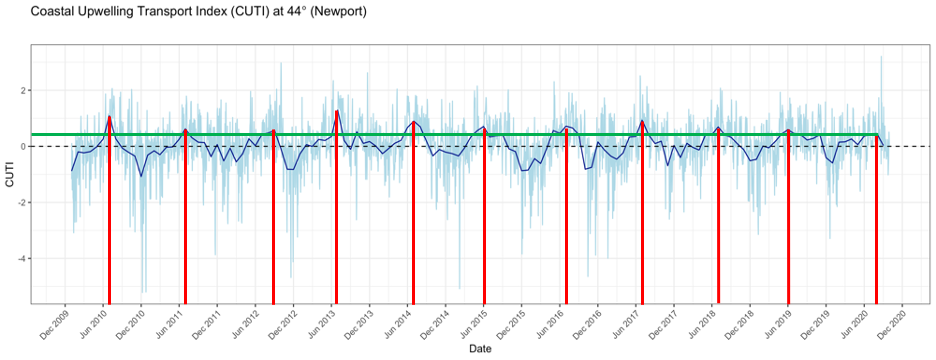

As I mentioned in a previous blog, this summer the coastal upwelling along the Oregon coast was delayed (Figure 1). Typically, peak upwelling occurs during the month of June or shortly thereafter, bringing nutrient-rich, deep waters to the surface and, when mixed with sunlight, a lot of productivity. This productivity sets off a chain of reactions — the input of nutrients leads to increased phytoplankton production, which in turn leads to increased zooplankton production, resulting in growth and development of larger organisms that consume zooplankton, such as rockfish and gray whales. If the timing of upwelling is delayed, then so too is this chain of reactions. As you can see from Figure 1, the red lines show that the peak upwelling this year occurred far later in the summer than any year in the last 10 years, with the exception of 2012. Gray whales may have cued into this delay and therefore also delayed their arrival to the PCFG feeding grounds, hence causing us to have low sighting rates at the start of our season. However, this is mostly speculative as we still do not understand the functional mechanisms by which cetaceans, such as gray whales, detect prey across different scales, and to what extent oceanographic conditions like upwelling may play a role in prey availability (Torres 2017).

Furthermore, the green line in Figure 1 shows that even after peak upwelling was reached this year, upwelling conditions were lower than all the other peaks in the previous 10 years. We know that weak upwelling is correlated to poor body condition of PCFG gray whales in subsequent years (Soledade Lemos et al. 2020). Upon arriving to the Oregon coast feeding grounds, gray whales may have noticed that it was shaping up to be a poor prey year (we certainly noticed it in Port Orford in the emptiness of our zooplankton net). Faced with this low resource availability, individuals had to make important decisions – risk staying in a currently prey-poor environment or continue the journey onward, searching for better prey conditions elsewhere. This conundrum is known as the marginal value theorem, whereby an individual must decide whether it should abandon the patch it is currently foraging on and move on to search for a new patch without knowing how far away the next patch may be or its value relative to the current patch (Charnov 1976). If we think of the Oregon coast as the ‘current patch’, then we can see how the marginal value theorem translates to the situation gray whales may have found themselves in at the start of the summer.

Yet, an individual gray whale does not make these decisions in a vacuum. Instead, all gray whales in the same area are faced with the same conundrum. Seminal work by Pianka (1974) showed that when resources, such as food, are abundant, then competition between predators is low because there is enough food to go around. However, when resources dwindle, competition increases and the niches of predators begin to overlap more and more. With Charnov and Pianka’s theories in mind, we can see two groups of gray whales emerge from our 2020 field work observations: those that stayed in the ‘current patch’ (Oregon) and those that decided to seek out a new patch in hopes that it would be a better one. Solé certainly belongs in the first group. We saw her consistently throughout the whole summer. In fact, she was oftentimes so predictable that we would find her foraging on the same reef complex every time we went out to survey. Smudge may also belong in this group, however it is hard to say definitively since we only survey in Port Orford in late July and August. In contrast, I would place whales such as Spray and Heart in the second group since we saw them early in the summer and then not again until mid-to-late September. Where did they go in the interim? Did they go somewhere else in the PCFG range? Or did they venture all the way up to Alaska to the primary Eastern North Pacific (ENP) gray whale feeding grounds? Did their choice to search for food elsewhere pay off?

As I said earlier, these are all just musings for now, but the GEMM Lab is already hard at work trying to answer these questions. Stay tuned to see what we find!

* Thanks to all the divers who assisted with the pilot CamDo season: Aaron Galloway, Ross Whippo, Svetlana Maslakova, Taylor Eaton, Cori Kane, Austin Williams, Justin Smith

References

Charnov, E.L. 1976. Optimal Foraging, the Marginal Value Theorem. Theoretical Population Biology 9(2):129-136.

Pianka, E.R. 1974. Niche Overlap and Diffuse Competition. PNAS 71(5):2141-2145.

Soledade Lemos, L., Burnett, J.D., Chandler, T.E., Sumich, J.L., and L.G. Torres. 2020. Intra- and inter-annual variation in gray whale body condition on a foraging ground. Ecosphere 11(4):e03094.

Torres, L.G. 2017. A sense of scale: Foraging cetaceans’ use of scale-dependent multimodal sensory systems. Marine Mammal Science 33(4):1170-1193.

Torres, L.G., Nieukirk, S.L., Lemos, L., and T.E. Chandler. 2018. Drone Up! Quantifying Whale Behavior From a New Perspective Improves Observational Capacity. Frontiers in Marine Science: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00319.