David P. Turner / May 6, 2021

A Great Transition is hopefully underway − from humanity’s current chaotic rush towards environmental disaster, to a more ordered Earth system in which the global human enterprise (the technosphere) becomes sustainable. However, achieving the necessary planetary scale organization of the human enterprise will be a challenge.

The discipline of systems theory offers insights into how new forms of order emerge, and here I will introduce two of its concepts − holarchy and metasystem transition − as they relate to the process of creating a sustainable planetary civilization.

The technosphere is commonly presented as a whole. I like to draw the analogy between the technosphere and the biosphere: both use a steady flow of energy to maintain and build order. Just as the biosphere evolved by way of biological evolution from microbes to a verdant layer of high biodiversity ecosystems cloaking the planet, the technosphere is evolving by way of cultural evolution into a ubiquitous layer of machines, artifacts, cities, and communication networks that likewise straddles the planet.

This formulation of the technosphere as a global scale entity is a glossy overview that allows one to make the point that the growth of the technosphere has altered the Earth system in ways that are toxic to some components of the biosphere, and indeed to the technosphere itself. Technosphere emissions of greenhouse gases leading to rapid climate change is the iconic example.

The view of the Earth system as composed of interacting spheres (geosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, cryosphere, technosphere) is also useful for imagining and modeling the feedbacks that regulate Earth system dynamics, e.g., the positive feedback of the cryosphere to climate warming in the atmosphere, or the negative feedback to climate warming by way of the geosphere-based rock weathering thermostat.

But systems theory offers another lens through which to examine the technosphere and its relationship to the contemporary Earth system. This view relies on further disaggregation.

Systems theory is a discipline that studies the origin and maintenance of order. The objects of study are systems − functional entities that can be analyzed in terms of parts and wholes.

Complex systems are often structured as holarchies , i.e., having multiple levels of organization. Complexity in general refers to linkages among entities at a range of spatial and temporal scales, e.g., a city is more complex than a household.

Like the more familiar hierarchy (e.g., a military organization), there are levels in a holarchy; lower levels are functional parts of the levels above. The entities (holons) at each level are “wholes” relative to the level below but “parts” relative to the level above. The difference between holarchy and hierarchy lies in representation of both upward and downward causation in a holarchy compared to primary concern with downward-oriented control in a hierarchy.

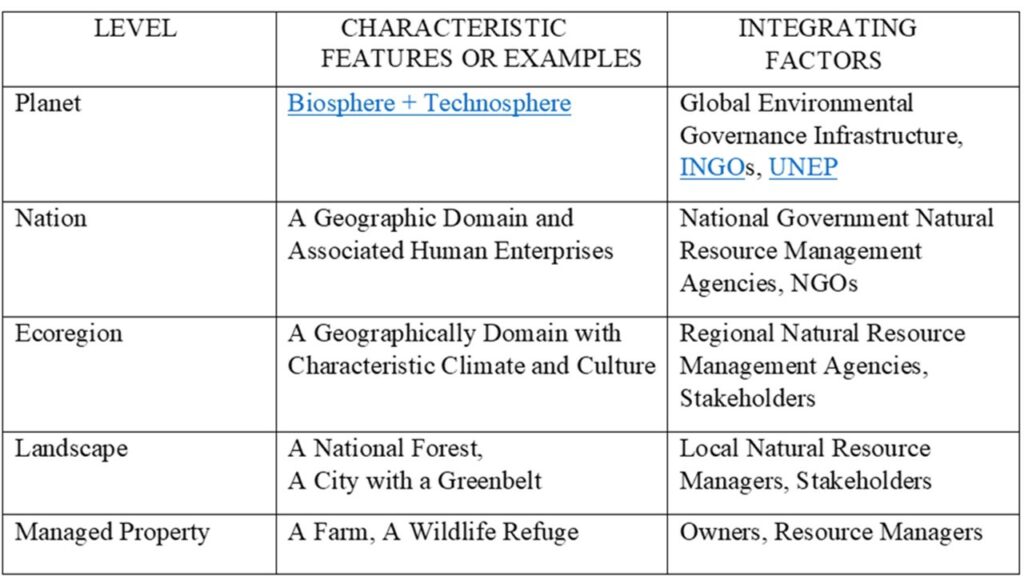

Let’s consider the environmental management aspect of the Earth system as a holarchy (Table 1).

Table 1. Levels in a planetary natural resources management holarchy. The Integrating Factors refer to how the components within a holon interact.

The emphasis in this management-oriented holarchy is on holons that consist of coupled biophysical and sociotechnical components. Environmental sociologists term a holon of this type a socio-ecological system (SES) (Figure 1). In an SES, stakeholders coordinate amongst themselves in management of natural resources.

Figure 1. A socio-ecological system holon. Integration of the Biophysical Subsystem and the Sociotechnical Subsystem is achieved by management of natural resources and delivery of ecosystem services. Adapted from Virapongse et al. 2016. Image Credit: David Turner and Monica Whipple.

At the base of the Earth system SES holarchy (Figure 2) are managed properties, such as a farm or wildlife refuge, where humans and machines manipulate the biophysical environment to produce ecosystem services such as food production and biodiversity conservation.

Figure 2. The planetary socio-ecological system holarchy. Arrows are indicators of interactions, with larger arrows suggestive of slower more powerful influences. Adapted from Koestler 1967. Image Credit: David Turner and Monica Whipple.

A step up, at the landscape level, are mosaics of rural and urban lands. A town with parks and an extensive greenbelt, or a national forest in the U.S., which is managed for wood production as well as water quality and other ecosystem services, are sample landscapes. Disturbances within a landscape, such as wildfire on the Biophysical side or a change in ownership on the Sociotechnical side, can be absorbed and repaired by resources elsewhere in the landscape (e.g., reseeding a forest stand after a fire).

At the ecoregion level, there is a characteristic climate, topography, biota, and culture. My own ecoregion, the Pacific Northwest in western North America, is oriented around the Cascades Mountains, coniferous forests, high winter precipitation, and an economy that includes forestry, fishing, and tourism. These features help define optimal natural resources management practices. A significant challenge at the ecoregion level is integration of management at the property and landscape scales with management of the ecoregion. Ecoregions interact in the sense of providing goods and services to each other, as well as collaborating on management of larger scale resources such as river basin hydrology.

The national level is somewhat arbitrary as a biophysical unit, but the sociotechnical realm is significantly partitioned along national borders, so the nation is in effect a clear level in our SES holarchy. Nations have, in principle, well organized regulatory and management authorities that aim for a sustainable biophysical environment as well as a stable and prosperous socioeconomic environment.

At the planetary level, the sociotechnical aim is to manage the global biophysical commons − the atmosphere and oceans − and coordinate across nations on transborder issues like conservation of biodiversity. That would mean agreements on policies to limit greenhouse gas emissions, reduce air and water pollution, and manage open ocean fisheries.

A strong global environmental governance infrastructure is needed at the planetary level to ensure a sustainable relationship of the technosphere to the rest of the Earth system.

But what we have now at the global scale is a weakly developed array of intergovernmental organizations (e.g., the United Nations Environmental Program), transnational corporations that heavily impact the global environment, and international nongovernmental organizations like Greenpeace. We do not have a fully realized planetary level of environmental governance.

The systems theory term for emergence of a new level in a holarchy is “metasystem transition”. This process involves an increasing degree of interaction and interdependency among the constituent holons (nations in this case). Eventually, positive and negative feedback relationships are established that promote coexistence and cooperation. The origin of the European Union is a relevant case study of a metasystem transition in the geopolitical realm.

Resistance to planetary scale management is understandable – notably because nations fear losing sovereignty. Less developed nations worry about external imposition of constraints on their economic development that may be unjust considering the global history of natural resource use. Working through these political issues is fraught with complications, thus the process would benefit from focused institutions. Global environmental governance researchers have proposed creation of a United Nations-based World Environment Organization, which would coordinate building environmental management agreements with follow through monitoring and enforcement.

A key driver for the success of planetary-level SES integration is that each nation is faced with environmental problems, like climate change, that it cannot address on its own. Survival will require a new level of integration with its cohort of national-level holons. Possibly, progress in collaboratively addressing global environmental threats like climate change could even lead to further progress in collaboratively addressing global geopolitical threats like the proliferation of nuclear weapons.