Redefining “Best Available Science”

Recently a major NGO and TV station ran a story covering our most recent report which covered costal futures of the US west coast county. Our report was made using some of the best available science, but in fact we have fallen short. While the science we used included was well supported and noteworthy, we failed to include knowledge that takes on a more transdisciplinary approach.

Expanding Knowledge

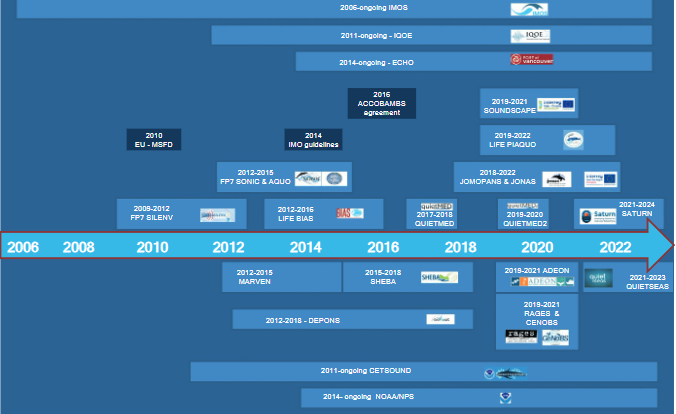

According to Robinson (2020), ocean sociotechnical imageries emerged new images of the ocean frontier in the mid-20th century. It helps to think further ahead about what technology may be available in the future as opposed to what is available at that moment. Levin et al. (2023), displays an example for us explaining how meetings with both contracting parties and experts of the Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP), can allow for better coordination as there will be more familiarity with technologies at hand. The “best available science” is not always what is readily available, sometimes it takes tracking down more information to be better educated.

Importance of Expansion

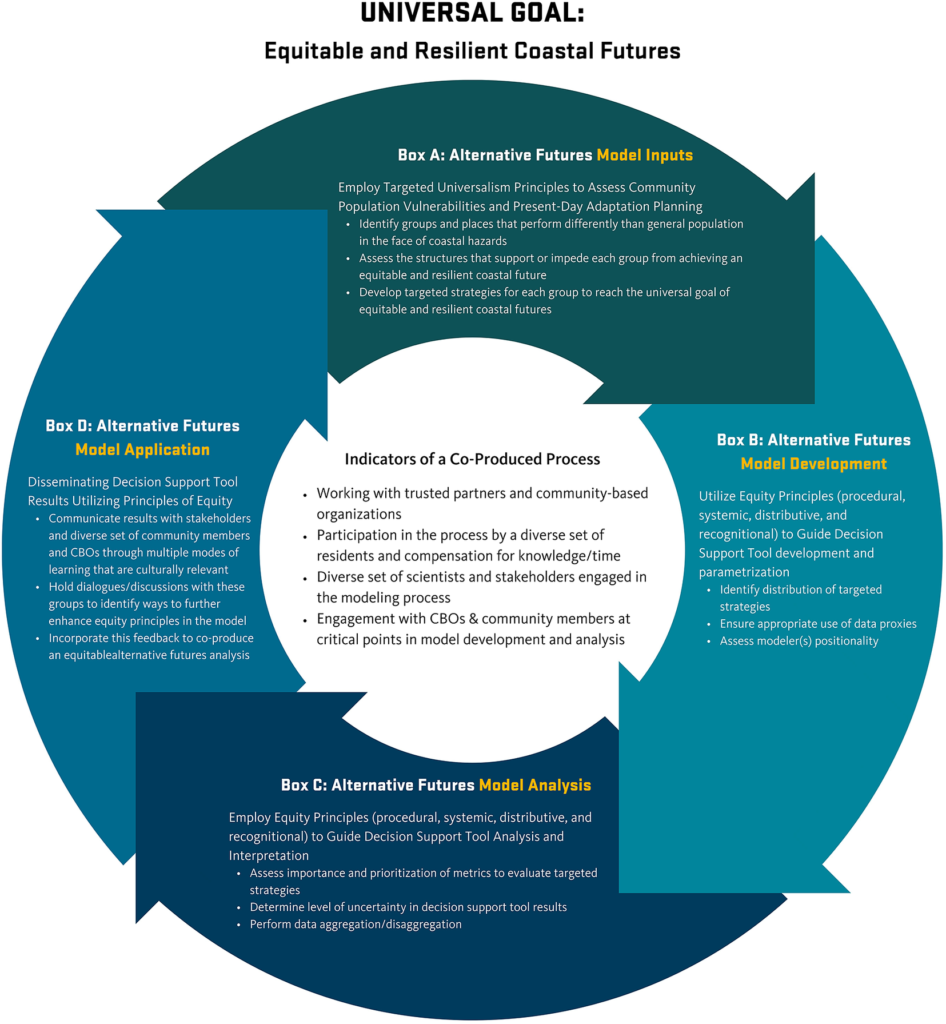

Transdisciplinary approaches provide great benefits for helping ocean and costal sciences. Kiatkoski Kim et al., (2022) explains how transdisciplinary research has proved to be successful at providing solution to environment problems as it brings science closer to society by bridging the gap of implementation. Another way in which this approach can prove to be beneficial beyond conducting research is through identifying needs or objectives. Stated by Proulx et al., (2021), through understanding the needs of indigenous communities by having an open mind, can lead to finding and acknowledging that both the scientific and indigenous communities may share similar objectives.

Challenges

Now while transdisciplinary approaches provide many benefits, there are challenges that come with it. One pointed out by Franke et al. (2021), is that prevailing disciplinary mindset within scientific communities challenge the transdisciplinary and socio-political environments where the research takes place. To overcome these challenges scientists must work transparently and professionally in order for this type of approach to work.

Closing Remarks

We view our past mistake as not so much of a mistake, but an opportunity to bring forth a better way of working within science. Moving forward our work will be sure to incorporate indigenous and local knowledge into our reports and all future work.

References:

Franke, A., Peters, K., Hinkel, J., Hornige, A.-K., Schlüter, A., Zielinski, O., Wiltshire, K. H., Jacob, U., Krause, G., and Hillebrand, H. (2021). Making the UN Ocean Decade Work? the potential for, and challenges of, Transdisciplinary Research & real-world laboratories for building towards Ocean Solutions.

Kiatkoski Kim, M., Douglas, M. M., Pannell, D., Setterfield, S. A., Hill, R., Laborde, S., Perrott, L., Álvarez-Romero, J. G., Beesley, L., Canham, C., and Brecknell, A. (2022). “When to use transdisciplinary approaches for environmental research.” Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10.

Levin, L. A., Alfaro-Lucas, J. M., Colaço, A., Cordes, E. E., Craik, N., Danovaro, R., Hoving, H.-J., Ingels, J., Mestre, N. C., Seabrook, S., Thurber, A. R., Vivian, C., and Yasuhara, M. (2023). “Deep-sea impacts of climate interventions.” Science, 379(6636), 978–981.

Proulx, M., Ross, L., Macdonald, C., Fitzsimmons, S., and Smit, M. (2021). “Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge and ocean observing: A review of successful partnerships.” Frontiers in Marine Science, 8.

Robinson, S. (2020). “Scientific Imaginaries and science diplomacy: The case of ocean exploitation.” Centaurus, 63(1), 150–170.