What are the stories we tell about our lives, our history, our gardens, our favorite flowers? I’ve been thinking about these things, and how we can personalize what’s happening in the world. How we bring issues of justice and equity into our lives as gardeners.

What can we do? How do we start? Why haven’t we done this earlier? What does this have to do with gardening?

These are all questions I’m hearing from Master Gardener leaders and volunteers throughout the state. Via Zoom, phone and email, I’ve been doing a lot of listening in my new role as statewide outreach coordinator, and asking questions.

And in the way of the world right now, I’m incredibly thankful to be learning so much, even as I’m unlearning stories I thought I knew. For example, while I have sentimental childhood memories of visiting Mt. Rushmore on a classic family road trip across the country, I know now that project defiled sacred Lakota land and that the creator, Gutzon Borglum, was deeply involved in the Ku Klux Klan.

I wonder why I never learned in school about what happened in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921, or the important significance of June 19th.

Facing our need as Master Gardeners to better serve our community through a lens of equity, diversity and inclusion means uncovering the truth, questioning our stories, and checking our own assumptions. It’s why I’m turning to the words of James Baldwin right now: Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Let’s start with the plants themselves.

Take hydrangea, one of my favorite plants. But it wasn’t always called hydrangea. Known and revered for centuries in Japan as ajisai, the flower was caught in the colonization sweeps of Joseph Banks. When it was presented at Kew Gardens in England, the “newly discovered” plant was renamed hydrangea, effectively erasing its Japanese cultural history and lineage.

And then there’s the dahlia….

Named for Swedish botanist Anders Dahl, the dahlia was brought to Europe by the Spanish after the conquest of Mexico. Grown in the beautiful and sophisticated gardens of Montezuma, the Aztecs called this flower cocoxochitl, where it was grown for its grandeur, function and as a food crop. The tree dahlias grown here could grow to thirty feet tall and with hollow stems three inches in diameter, they were used for transporting water. All of this rich, Mexican, cultural history vanished when it was claimed and named by Europeans.

“This naming of things is so crucial to possession—a spiritual padlock with the key thrown irretrievably away—that it is a murder, an erasing, and it is not surprising that when people have felt themselves prey to it (conquest), among their first acts of liberation is to change their names (Rhodesia to Zimbabwe, LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka). That the great misery and much smaller joy of existence remain unchanged no matter what anything is called never checks the impulse to reach back and reclaim a loss, to try and make what happened look as if it had not happened at all.”

—Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Story)

The author Jennifer Jewell writes about her interview with Jamaica Kincaid:

In my conversations with Jamaica Kincaid … she said this: “The thing we have liked the most about gardens is the love of a flower from somewhere else. Most people don’t know that the marigold and dahlia were part of Montezuma’s gardens. If we could just honor one another, it wouldn’t feel so badly to have taken them. Honoring one another is one way perhaps that we redeem ourselves; I am very interested in redemption,” she told me. Redemption. An interesting word – Jamaica talks about how we as people can work to honor one another – work to re-find and retell and re- share histories which were hidden – stolen – histories that some strove to erase. But they are still there those histories – embodied in the plants and the seeds and the art and the myth and the lived history of peoples and places.

I have two stories to leave you with. One is a tiny example of what can happen when we begin to ask questions and see things with a new eye. I recently noticed the description for Trachelospermum jasminoides on a favorite plant resourcing site. Common names listed were star jasmine and confederate jasmine. Do we really need to celebrate the confederacy with one of my favorite plants? Probably not. I mentioned it to the website owner and within ten minutes, the name confederate jasmine was gone.

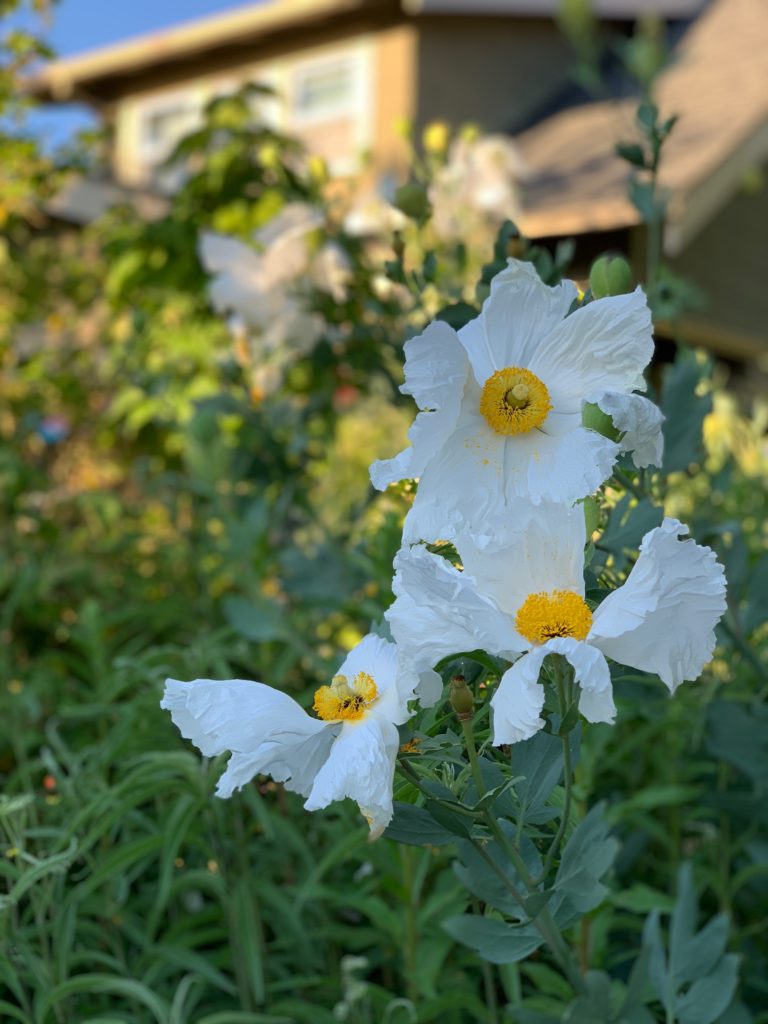

But then there’s the story the woman riding her bike by our garden told herself a few weeks ago. My partner and I were gardening in our front garden, and the bicyclist pulled a u-turn when she saw our giant stand of romneya coulteri. Approaching my partner she asked about the flower, first inquiring if she was the landscaper. My partner is Mexican-American, had a bandana holding back her hair, and earbuds in her ears. The woman repeated the question, this time overpronouncing with the assumption she might not speak English. I couldn’t believe what I was witnessing. I’ve never been assumed to be the landscaper in our front garden. And that was my white privilege.

We all have stories to unlearn and we’re in a special moment where we can use new eyes in the way we see and move through the world. And we can act. Even in our gardens.

Resources mentioned in this essay:

- Listen to the podcast Cultivating Place with Jennifer Jewell, and her episode with Jamaica Kincaid.

- Read Jamaica Kincaid’s book, My Garden (book)

- Listen to an audio recording of Jamaica Kincaid speaking on Oppression in the Garden

- Follow the hashtag #decolonisethegarden on instagram for more stories of the colonization of plants.

- Follow botanist Justin Robinson on Instagram for meaningful stories and more about the colonization of plants.

By LeAnn Locher, Statewide Master Gardener Outreach Coordinator

You used the term “master gardeners” without capitalization or TM. Does this mean we are finally getting rid of the term “Master” and will move on? The quote in your piece “This naming of things is so crucial to possession” is so telling.

Good eye Marcia! At 1.5 months in on the job I thought I had the capitalization and TM thing down but I obviously do not. As to your bigger question, let’s ask questions about that. What does it mean to you? What do you think it means to others?

Hi Marcia,

I fixed the capitalization on Master Gardener. The OSU editors and style guide have suggested that we not use the TM with each use of the term (even though OSU continues to maintain the service mark) because it is distracting to readers. Thus, I only use the TM in formal pubs, and only at first use of the term.

We have started to discuss the use of, and potentially dropping ‘Master’ from OSU Extension volunteer program names – but need to have much more extensive discussions (with the National MG group, with MG coordinators, and with volunteers) before we make that change.

I thought perhaps you intentionally had used lower-case. The issue of using the term “Master” has been around our state group sporadically for a long time (but I have been a member only since 2004). Demographics are clear; most members are female and white (plus other categorizations such as over 50, etc.). Our mission is education, not dominance, not superiority. It’s time to make the change away from “Master.”

The term ‘Master’ in this context just refers to a mastery or thorough understanding of the subject.

Some other Extension services have a volunteer role called “Extension Gardener” and participants act as educators the same way as “Master Gardeners”.

I’m sure that expressing mastery of a subject was the original intention. For many people, “Master” does carry a connotation of enslaver.

One thing I have noticed is that sometimes, members of the public think that “Master Gardener” means that the volunteer has an advanced degree in horticulture. This misconception can put a lot of pressure on volunteers, even folks who are exceptionally skilled.

The current name certainly identifies the program and at this point is associated with the useful services that this committed corps for volunteers offers the community. I do wonder who is engaging with us and who’s not, based on how we identify ourselves. I’ll be interested to continue the conversation about this topic.

Marcia, thank you for starting this conversation about the word “master.” Use of this word in terms of our role as a garden educators is troubling to me as well. I am relieved to hear that there is discussion going on at the state level to consider the historical implications of this word in the US and possible alternatives.

LeAnn, thanks for sharing that story, your insights, and especially that cocoxochitl .

A good question for readers: what are three words about how you might feel if a loved one were gardening and a passer-by assumed that they were “the help”? What if this was not the first time that this situation happened to your loved one, or to you?

My feelings in this situation would be sad, angry and frustrated.