This article has its roots in a discussion I had with an Ecampus intern about going on the job market. This intern is working in an academic technologies role at a higher ed institution already, but also getting the Instructional Design certificate here at OSU. It was my first time thinking about what the growth of instructional design certificate and degree credentials means for all instructional designers. Very few of the instructional designers I’ve met and worked with here or at my previous institutions actually have degrees in instructional design, including myself. The field of instructional design emerged out of a specific institutional and educational need in higher education and corporate education, which makes for an ever-growing, ever-changing, but always innovative membership. How do we, as a field, continue to be inclusive of all instructional designers, regardless of their academic or educational backgrounds?

One potentially positive fact is that academia moves very slowly, so we have some time to strategize. Instructional design is still an emerging speciality within higher education, with each institution classifying that role differently, and providing that role with different levels of support. Some institutions, even today, do not have any instructional designers. Current research indicates that this must change. One of the best sources of data about the field of instructional design in higher education and instructional designers is the Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE) Project. The participants in the CHLOE survey are “the senior online officer at each participating institution.” This survey pool recognizes the variance in organizational structures at different institutions by focusing on the COO’s purview. In the 2019 CHLOE 3 survey, it was reported that the median number of instructional designers employed at 2-year colleges, and public and private 4-year institutions, was four, regardless of enrollment or institution size. In CHLOE 7, one of the conclusions was that “insufficient instructional design staffing may be one of online learning’s most serious long-term vulnerabilities,” with only 10% of Chief Online Officers surveyed describing their ID capacity as sufficient for their current needs, and only 3% believing they would be able to meet anticipated need.

These findings signal that universities should be moving towards a significant fiscal investment in hiring instructional designers. Joshua Kim wrote a few key takeaways from the CHLOE 7 in CHLOE 7: The Present and Future of Instructional Design Capacity. Kim predicts that universities will need to not only hire more instructional designers, but that these roles will need to be hybrid or remote to attract the post-pandemic workforce. In addition to hybrid and remote options, Kim posits that, “Forward-thinking universities may find that they need to start offering star non-faculty educators the same recognition and incentives that have long been necessary to recruit and retain star tenure-line faculty.” But what does this mean for instructional designers? How would an instructional designer even be able to become identified as a “star” within the field or even at a specific institution?

Understanding Branding for Faculty and Non-Faculty Educators

Circling back to my initial inquiry about what instructional designers can do to ensure the field stays inclusive, I believe an individual enterprise will have a collective impact that will benefit the largest number of people: personal branding. In What’s the Point of a Personal Brand? Executive coach Harrison Monarth uses the story of his client, Mike, to illustrate how important it is for employees to think about how personal branding is now a strategy for gaining visibility within organizations, and that visibility is now a key component when employers are thinking about promotion. Monarth observes that “In high-performing organizations, at certain levels, everyone is exceptional. To clearly differentiate your value and what you bring to the table, you need to do more than have a good reputation. You need to have an outstanding personal brand.” Having a brand isn’t the same thing as being a celebrity, although I think many would agree that there are celebrities in every field, even instructional design.

Creating a personal brand is a successful career strategy outside of the corporate world as well, and one of the fields that is encouraging faculty to think about branding is not, as one might think, business but medicine. In 2019, the Academic Medicine blog published Knowing Your Personal Brand: What Academics Can Learn From Marketing 101, the purpose of which was to persuade medical professionals that a brand identity can be empowering. According to the article,

[K]nowing one’s academic brand can (1) help faculty members approach projects and other responsibilities through the lens of building or detracting from that brand, (2) provide a framework for determining how faculty members might best work within their institutions, and (3) help faculty members better understand and advocate their own engagement and advancement.

Although this article specifically speaks to and about academic teaching faculty, Instructional designers at institutions are often placed in the professional faculty role, along with librarians or program directors, and have many of the same professional demands on their job descriptions. As former faculty, I can attest that both of my careers have included independent research, departmental service, and conference or publication responsibilities.

Finding Your Personal Brand

If a brand is defined as opinions that people have about you based on your work, it is important to be self-aware, and intentional about the work that you do. Creating your brand can be a difficult task if, like me, you have a variety of experiences and interests. It requires self-reflection about one’s accomplishments and body of work as a whole, and the need to generalize what are sometimes very disparate activities. In Using Your Personal Mission Statement to INSPIRE and Achieve Success, an article published in Academic Pediatrics, the official journal of the Academic Pediatric Association, the authors describe a framework for building a personal mission statement (INSPIRE):

- Identify Your Core Values

- Name the Population You Serve

- Set Your Vision

- Plan How You Will Achieve Your Vision

- Identify Activities That Align With Your Mission

- Review, Revise, and Refine Your Mission Statement

- Enlist Others to Help You Accomplish Your Mission

A slimmed down version of this same framework can be a helpful starting point for creating a brand identity. It enables you to identify your core values, name the population you serve, and identify activities that support those values and populations. But unlike a mission statement, this framework is best completed in reverse; a backwards brand design, if you will. (Sidenote: Instructional designers love to do things backwards). I call this framework SIFT:

- Start with your experience and accomplishments

- Identify keywords or topics

- Frame your work and interests

- Tie everything together

I believe that SIFT-ing has the potential to be a reflective process that will lead to a changing self-awareness of different types of instructional designers, for ourselves, and collectively.

Start with your experience and accomplishments

The best place to begin is with your complete resume or CV. It might be tempting to start with the tailored version you used to get your last position, but you don’t want to limit your view to only things that you think are relevant to instructional design. I can trace some elements of my brand back to my undergraduate and graduate degrees. I also include my two years as a contracted captioner for 3play and Rev within the same brand. Finding a brand that encompasses all that you are will only be successful if you use the most complete picture of yourself.

Identify keywords or topics

Your brand is more than just the places that you’ve worked at, the committees you’ve served on, and projects you’ve worked on. To understand your brand, you should begin by identifying a perspective, or positionality, that informs the decisions you’ve made in the past, however unconsciously that might have been, and looks towards the future. Keywords can be a useful next step, but you will want to avoid the potential to find yourself trapped within categories! In a field like medicine, there are already established research interests and specialties. As a field, instructional design hasn’t reached the point of specialization, but we are trending towards accepting that there are too many topics that fall under the broad umbrella of instructional design for everyone to be experts in everything. For example, the Quality Matters Instructional Designers Association has 21 expertise categories that you can select from when joining the association that others can use to find you to connect with you.

When I first joined the QM IDA, I didn’t know what boxes to check, or even what some of these categories were. And since they are presented without explanation, the criteria for self-identification are unclear. I can check almost all of these boxes as things I have experience in—with the exception of K12 and the Continuing and Professional Education Rubric, but is experience the same thing as expertise? It might be my imposter syndrome talking, but I am more inclined to identify with interests than areas of expertise. (Sidenote: I still haven’t checked any boxes.)

Frame your work and interests

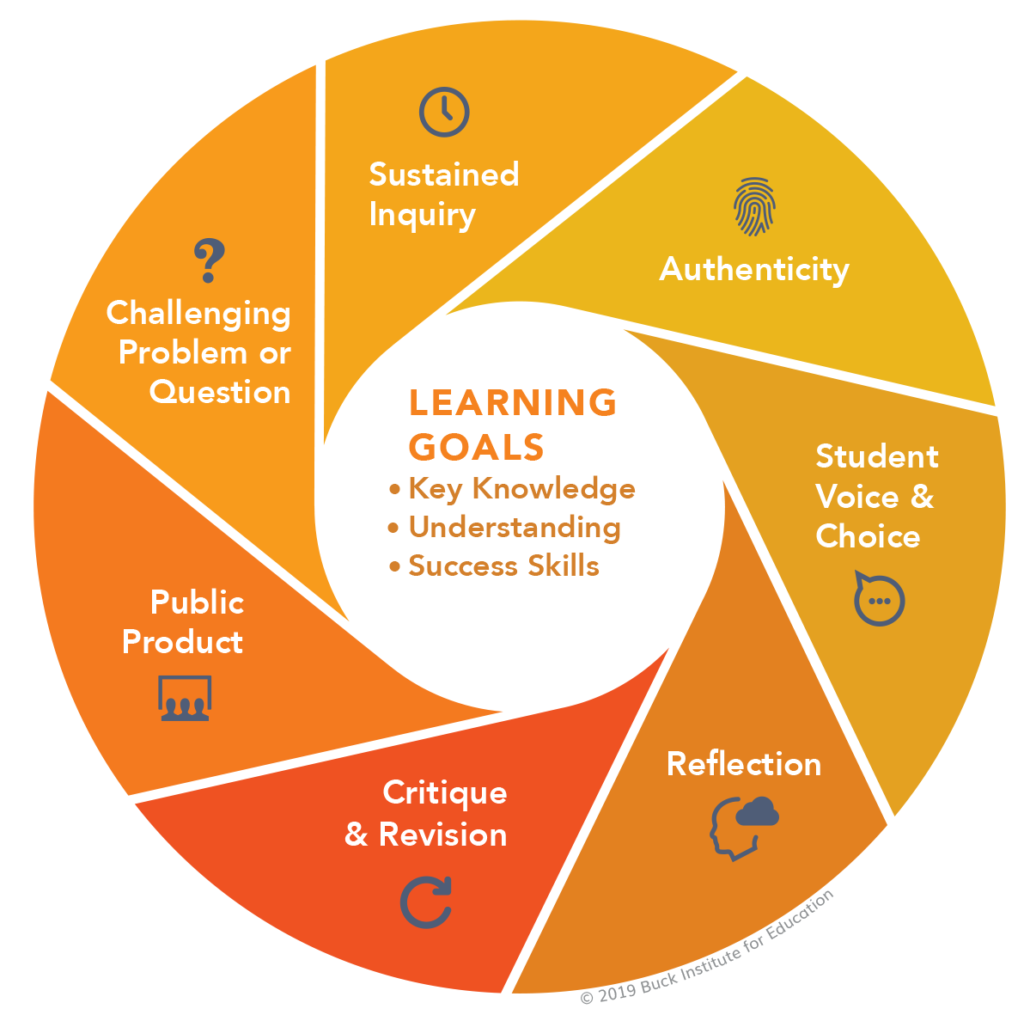

I hadn’t noticed a pattern to my interests while I was doing them, but by reflecting on my professional journey, I realized that I could trace one interest all the way back to my undergraduate honors thesis, through to my current career as an instructional designer. I’ve always had an interest in communities and the community spaces they inhabit—especially if they are online. Community doesn’t appear on QM’s list of categories, but it is the lens through which I approach many of the categories on that list. Accessibility, Computer-Based Learning, Distance Education, Hybrid instruction/Design, LMS, Multimedia Creation, Problem-Based Learning—all of these categories need to address questions of community by addressing inclusivity, access, equity, and authentic student-student and student-teacher interactions. Community is the keyword I use to frame my research interests and approach to instructional design, in all of its various forms.

Tie everything together

If you go to my LinkedIn profile, you’ll see that I have “Humanities girl in an instructional technology world” as my headline. That’s my brand. You might notice that it does not include “instructional design” or “community.” But at the same time, by labeling myself a humanist, I am evoking the words associated with humanities and humanism–things like communities, kindness, compassion, human potential, and the arts. Technology is often viewed either as the savior of humanity, or its destruction. In reality, of course, it’s both. By framing myself as a humanist working with technology, I am clueing people in that my perspective on technology will incorporate potential negative impacts for people. The playful nature of the headline i.e. using “girl” to rhyme with “world” also reveals my personality. Compare this headline with something like, “I am interested in humane approaches to technology used in education.” It’s true, but it doesn’t tell you about me as a person outside of my interests.

Being “On Brand”

To declare a brand is not to limit your interests, nor should it be criticized as promoting a non-interest in other topics. Another observation from Kim is that instructional designers are likely very busy, and overstretched. In his words, there is “a significant mismatch between institutional demand for instructional design services and the available supply.” To avoid burnout, instructional designers need to be strategic with the projects they commit to. A brand can also help you be selective about which conferences you attend, or committees you serve on. Being “on brand” can be a way of focusing your energy, and also a touchstone of your identity.

Using the SIFT framework, you can reflect on your professional values, and your professional goals. One of my colleagues in the field is an accessibility expert, and gets called in to consult on all things related to accessibility in addition to her daily work as an instructional designer. She recently became a certified Accessibility Professional with the IAAP, and this credential is visible on her LinkedIn profile as an emblem of her brand. Knowing her brand allowed her to appeal to her institution to allow her this opportunity that enriches not only her own skillset, but the prestige of her institution by having an IAPP certified accessibility professional on their staff. In that sense, personal branding can also help institutions build diverse departments that are teams of specialists.

To return to the three benefits of branding for faculty outlined in the Academic Medicine article, knowing my brand helps me decide where to devote my limited bandwidth by pursuing professional activities that are “on brand” for me. I can also use my brand to search for specific opportunities that will build my brand, even if those fall outside the typical skillset of instructional designers. However, moving towards a “branding” mindset also benefits my colleagues, who are equally, individually, uniquely talented, and should be recognized for their specialties and allowed to follow their passions, rather than be constrained to their job duties. As instructional design teams at universities grow, having a team of specialists can also help alleviate burnout by allowing people to play to their strengths. This can ensure that instructional design remains a space where all career pathways are valid and not contingent on specific credentials.

References

Borman-Shoap, Emily, Li, Su-Ting T., St Clair, Nicole E., Rosenbluth, Glenn, Pitt, Susan, and Michael B. Pitt. Knowing Your Personal Brand: What Academics Can Learn From Marketing 101 Academic Medicine 94(9):p 1293-1298, September 2019.

Kim, J. CHLOE 7: The Present and Future of Instructional Design Capacity InsideHigherEd (2022)

Li, Su-Ting T., Frohna, John G. and Susan B. Bostwick. Using Your Personal Mission Statement to INSPIRE and Achieve Success View from the Association of Pediatric Program Directors 17(2): p107-109, March 2017.

Monarth, H. What’s the Point of a Personal Brand? Harvard Business Review (2022)

Uranis, J. Definition Update: Chief Online Learning Officer (COLO) (2023)