Correlation does not equal causation. This phrase gets mentioned a lot in science. In part, because many scientists can fall into the trap of assuming that correlation equals causation. Proof that this phrase is true can be found in ice cream and sharks. Monthly ice cream sales and shark attacks are highly correlated in the United States each year. Does that mean eating lots of ice cream causes sharks to attack more people? No. The likely reason for this correlation is that more people eat ice cream and get in the ocean during the summer months when it’s warmer outside, which explain why the two are correlated. But, one does not cause the other. Correlation does not equal causation.

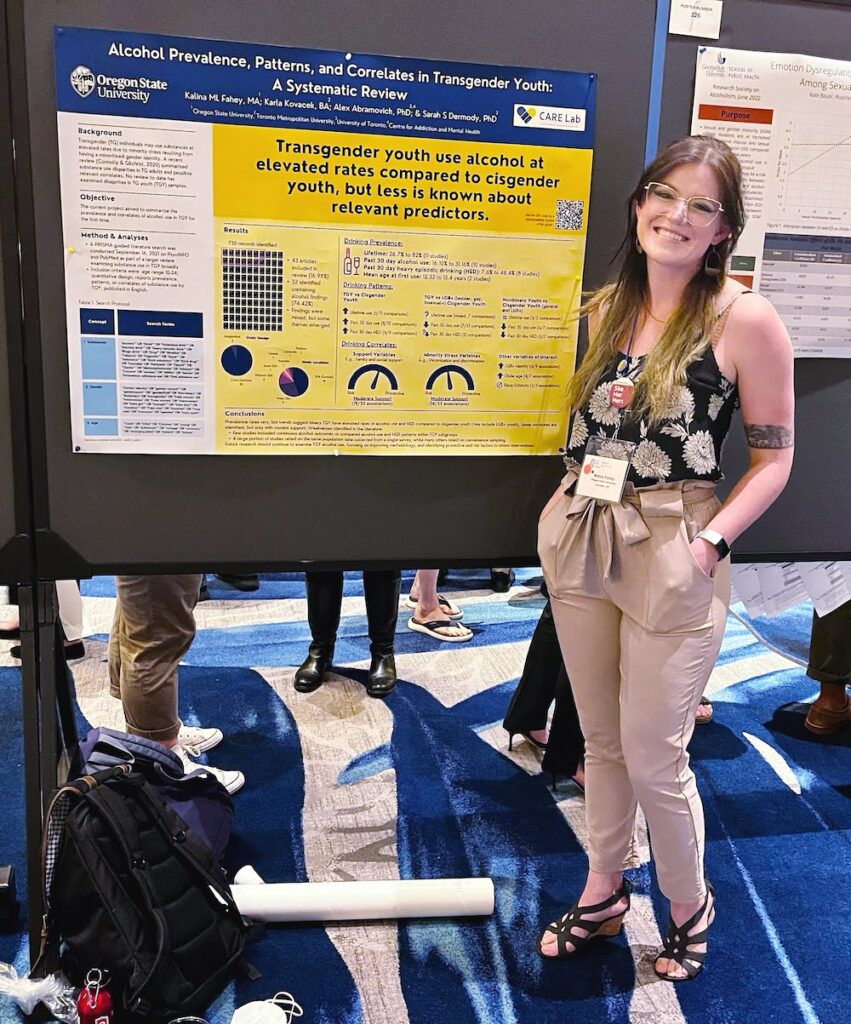

To date, much of the research that has been conducted on LGBTQ+ health has been correlational. Our guest this week, Kalina Fahey, hopes that her dissertation project will play a part in changing this paradigm as she is trying to get more at causation. Kalina is a 5th year PhD candidate in the School of Psychological Science working with her advisors Drs. Anita Cservenka and Sarah Dermody. Her research broadly investigates LGBTQ+ health disparities and how stress impacts health in LGBTQ+ groups. She is also interested in understanding ways in which spiritual and/or religious identities can influence stress, and thereby, health. To do this, Kalina is employing a number of methods, including undertaking a systematic review to synthesize the existing research on substance use in transgender youth, analyzing large-scale publicly available datasets to look at how religious and spiritual identity relates to health outcomes, and finally developing a safe experiment to look at how specific forms of stress impact substance use-related behaviors in real time.

Most of Kalina’s time at the moment is being spent on the experimental portion of her research as part of her dissertation. For this study, Kalina is adapting the personalized guided induction stress paradigm, with the aim of safely eliciting minor stress responses in a laboratory setting. The experiment involves one virtual study visit and two in-person sessions. During the first visit, participants are asked to describe a minority-induced stressful event that occurred recently, as well as a description of a moment or situation that is soothing or calming. After this session, Kalina and her team develop two meditative scripts – one each to recreate the two events or moments described by the participant. When the participant comes back for their in-person sessions, they listen to one of two different meditative scripts and are asked a series of questions regarding their stress levels. Kalina and her team also are collecting saliva and heart rate readings to look at physiological stress levels. This project is still looking for participants. If you are a sexual-minority woman who drinks alcohol, consider checking out the following website to learn more about the study: https://oregonstate.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_8e443Lq10lgyX66?fbclid=IwAR3XOdECIOvCbx1xn3QA5rrCtHfSezZrR5Ppkpnd9sx1SsicZRQnfYHAqb8. Kalina hopes to continue experiment-based research on LGBTQ+ health disparities in the future as she sees the lack of experimental studies to be a major gap in better understanding, and thereby supporting, the LGBTQ+ community.

Interested in learning more about Kalina’s research, the results, and her background? Listen live on Sunday, January 15, 2023 at 7 PM on 88.7 KBVR FM. Missed the live show? You can download the episode on our Podcast Pages! Also, check out her other work here or finder her on Twitter @faheypsych