This week we have a Fisheries and Wildlife Master’s student and ODFW employee, Gabriella Brill, joining us to discuss her research investigating the impact of dams on the movement and reproduction habits of the White Sturgeon here in Oregon. Much like humans, these fish can live up to 100 years and can take 25 years to fully mature. But the similarities stop there, as they can also grow up to 10 ft long, haven’t evolved much in 200 million years, and can lay millions of eggs at a time (makes the Duggar family’s 19 Kids and Counting not seem so bad).

Despite being able to lay millions of eggs at a time, the White Sturgeon will only do so if the conditions are right. This fish Goldilocks’ its way through the river systems, looking for a river bed that’s just right. If it doesn’t like what it sees, the fish can just choose not to lay the eggs and will wait for another year. When the fish don’t find places they want to lay their eggs, it can cause drastic changes to the overall population size. This can be a problem for people whose lives are intertwined with these fish: such as fishermen and local Tribal Nations (and graduate students).

The white sturgeon was once a prolific fish in the Columbia River and holds ceremonial significance to local Tribal Nations, however, post-colonialization a fishery was established in 1888 that collapsed the population just four years later in 1892. Due to the long lifespan of these fish, the effects of that fishery are something today’s populations have still not fully recovered from.

Can you hear me now

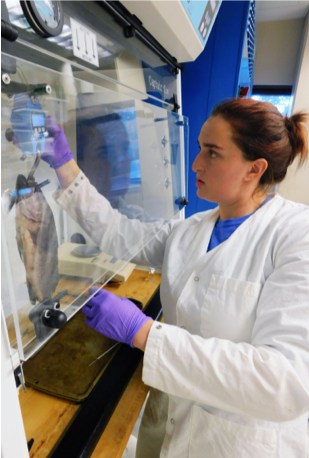

Gabriella uses sound transmitters to track the white sturgeon’s movements. Essentially, the fish get a small sound-emitting implant that is picked up by a series of receivers – as long the receivers don’t get washed away by a strong current. By monitoring the fish’s journey through the river systems, she can then determine if the man-made dams are impacting their ability to find a desirable place to lay eggs.

Journey to researching a sturgeon’s journey

Gabriella always gravitated towards ecology due to the ways it blends many different sciences and ideas – and Fish are a great system for studying ecology. She started with studying Salmon in undergrad which eventually led to a position with the ODFW. Working with the ODFW inspired her to get a Master’s degree so that she could gain the necessary experience and credentials to be a more effective advocate for changes in conservation efforts that are being made. One way to get clout in the fish world: study a highly picky fish with a long life cycle. Challenge accepted.

To hear more about these finicky fish be sure to listen live on Sunday February 26th at 7PM on 88.7FM, or download the podcast.