By Lisa Hildebrand¹ and Samara Haver²

¹PhD Student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

²Postdoctoral Scholar, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Cooperative Institute for Marine Resources Studies, Hatfield Marine Science Center

Many aspects of studying cetacean ecology, behavior, population dynamics, health, and sociality depend on being able to see and/or sample cetaceans when they come to the surface. While this research is not necessarily easy given that cetaceans spend the majority of their time underwater out of human sight, it is definitely feasible, as evidenced by decades of cetacean research. However, in order for researchers to observe cetaceans at the surface they need to get out to sea, and this boat-based effort can realistically only be done in good ocean conditions. Any sea-going individual likely uses the Beaufort sea state (BSS) scale as a measure of ocean conditions. For a full breakdown and excellent explanation of what the BSS is, check out our beloved Alexa’s blog; but for the purposes of this blog all you really need to know is that the smaller the BSS (which starts at 0), the calmer the ocean, and the higher the BSS, the rougher & stormier the ocean. There are two main reasons for conducting cetacean research in low BSS: 1) above a certain threshold (usually BSS 4) it becomes difficult to reliably spot and recognize cetaceans at the surface, thus compromising good data collection, and/or 2) to ensure safety and comfort of the research team.

So, when the BSS gets too high, us humans usually do not go out to sea to study cetaceans, which means that the cetaceans, for the most part, go unobserved. So, many questions arise about what cetaceans are doing during these rough ocean conditions. What does an increased BSS mean for them? Are they unfazed by big waves and strong winds, or are they affected by the weather and take longer dives or seek out fairer seas? A conversation among friends sparked our curiosity of what cetaceans do in stormy conditions and inspired us to collaborate on this blog. Here, we report on what is and is not known about cetaceans in storms, and discuss some ideas about how best to quantify the effects of rough sea conditions on cetaceans.

A literature search of cetaceans during storms did not generate many results, which was not surprising to us given the above reasons about researchers not being able to survey in rough sea conditions. However, we did find a couple of interesting studies about cetacean behavior and distribution after storms.

Changes in foraging behavior

Autumnal storms in Maryland, USA resulted in less frequent and shorter encounters of bottlenose dolphins in the US Mid-Atlantic Bight. However, dolphins spent a significantly higher percentage of their encounters feeding after storms than they did before or during them (Fandel et al. 2020). Similarly, bottlenose dolphins in Mississippi Sound displayed an approximately 15% increase in foraging activity for up to 2 years following Hurricane Katrina (Smith et al. 2013). These changes in foraging behavior are attributed to shifts in distributions and behavior of dolphin prey species as a result of altered environmental conditions (primarily sea surface temperature and salinity) following the hurricanes.

Out-of-habitat events and strandings

An out-of-habitat event occurs when an animal is displaced out of its typical habitat. Seven of these events were reported following Hurricane Rita, which hit the southwest Louisiana coast in 2005, with bottlenose dolphins found in flooded roadside ditches, canals, shallow flooded fields, and a natural creek area (Rosel & Watts 2008). These locations ranged from 2.5 to 11 km inland from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, where these dolphins were displaced from. It is believed that the animals were carried inland on the storm surge that accompanied Hurricane Rita and were left stranded in areas that held water the longest once it started receding (Rosel & Watts 2008).

There have been two mass strandings of pygmy killer whales that are believed to have been a result of hurricanes. In 1995, five pygmy killer whales stranded (three of which died, while two were successfully refloated) in the British Virgin Islands a day after Hurricane Marilyn (Mignucci-Giannoni et al. 1999). In 2006, six pygmy killer whales (five of which died) stranded in New Caledonia during and after Hurricane Jim (Clua et al. 2014). Both studies hypothesize that increased energetic costs, as a result of attempting to evade the hurricanes, coupled with animals becoming disoriented and ending up in shallow waters, is what caused them to strand.

While these studies reveal post-storm effects on cetaceans, we still do not know exactly how these individuals behaved during the storms. Did they attempt longer dives to stay away from the rough conditions at the surface, thus becoming disoriented? Or were they behaving normally (i.e. foraging, travelling) and were simply “pushed” into waters that they did not intend to go into? Given that very stormy sea conditions do not allow for visual, boat-based surveys, we need to employ different technologies to study cetacean behavior and distribution during storms.

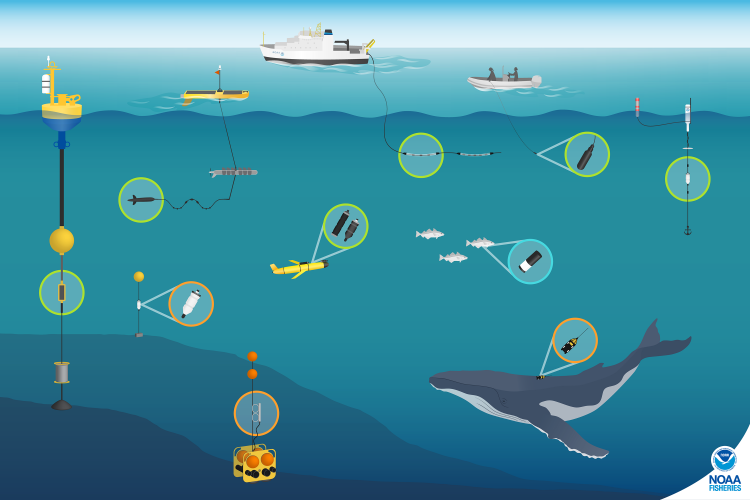

Passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) is a great tool that can monitor ocean environments for us when the seas are too stormy. Using fixed or mobile platforms, underwater PAM listening devices (hydrophone and data storage) can record sounds in the ocean for us to listen and analyze from shore. With PAM we are able to track the vocalizations of marine mammals as well as other sounds in the environment, such as waves crashing and rain. Anecdotally, we have spent many days at sea in conditions that were too rough for visual observations, but we could safely use our PAM tools to detect cetaceans. So, just because the seas may be too rough to see cetaceans, this fact does not mean that we cannot observe them – we just need to listen instead of look.

A number of studies have investigated whether whales change their vocalization behavior differently in response to changing ambient sound conditions (for example: Dunlop et al. 2010; Fournet et al. 2018). While research on ocean sound levels is often focused on the impact of human-generated or anthropogenic noise, there are also natural, abiotic sound sources (e.g. wind, rain, ice) that can elevate ambient sound levels. One potential animal response to elevated ambient sound levels is to vocalize at a higher intensity, called the Lombard (or cocktail party) effect. This phenomenon is common for us humans – have you ever been at a party and at some point you realize that you are shouting to someone in order to be heard above the noise of the room? That’s the Lombard effect! Humpback whales in Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska, exhibited the Lombard effect in response to both natural and man-made sounds, but the probability of calling was lower when vessels were present compared to times with only natural sounds (Fournet et al. 2018). It is also possible that whales may vocalize at different frequencies, times, or for shorter durations when the ocean becomes louder, which we can easily track with PAM. Unfortunately, PAM is limited to what we are able to hear, so if we do not hear whales we cannot determine if this result is because their vocalizations are masked by higher intensity sounds, if they stopped vocalizing, or if they left the listening area.

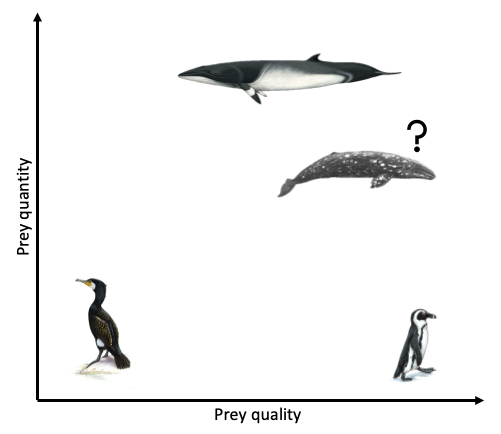

Animal-borne tags are another kind of autonomous observation tool that could help us understand cetacean behavior and distribution in storms. Admittedly, the logistics of applying tags before an imminent storm are probably complex. However, the development of medium-duration archival tags may provide a good trade-off between deploying tags long enough before a storm begins, thus providing safe working conditions for the research team, while minimizing potential physical impacts to the animals (Szesciorka et al. 2016). There are currently no published tag studies that document cetacean behavior during storms, but a study of a gray-headed albatross, fitted with a satellite transmitter, that successfully foraged during an Antarctic storm (Catry et al. 2004) shows the promise of using animal-borne tags to answer these questions.

As with many questions about animal behavior, our best option is to combine all of our research tools to piece together evidence about what might be going on in the deep, dark, stormy ocean. Simultaneously collecting acoustic and movement & behavior data through PAM and animal-borne tags, respectively, could allow us to determine how cetaceans behave during storms. While we are probably not poised to tackle these questions right now, perhaps another curious graduate student can take it on for their own PhD research…

References

Catry, P., Phillips, R.A., and J.P. Croxall. Sustained fast travel by a gray-headed albatross (Thalassarchie chrysostoma) riding an Antarctic storm. The Auk 121(4):1208-1213.

Clua, E.E., Manire, C.A., and C. Garrigue. 2014. Biological data of pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata) from a mass stranding in New Caledonia (South Pacific) associated with Hurricane Jim in 2006. Aquatic Mammals 40(2):162-172.

Dunlop, R.A., Cato, D.H., and M.J. Noad. 2010. Your attention please: increasing ambient noise levels elicits a change in communication behaviour in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277(1693):doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2319.

Fandel, A.D., Garrod, A., Hoover, A.L., Wingfield, J.E., Lyubchich, V., Secor, D.H., Hodge, K.B., Rice, A.N., and H. Bailey. 2020. Effects of intense storm events on dolphin occurrence and foraging behavior. Scientific Reports 10:19247.

Fournet, M.E.H., Matthews, L.P., Gabriele, C.M., Haver, S., Mellinger, D.K., and H. Klinck. 2018. Humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae alter calling behavior in response to natural sounds and vessel noise. Marine Ecology Progress Series 607:251-268.

Mignucci-Giannoni, A.A., Toyos-González, G. M., Pérez-Padilla, J., Rodríguez-López, M. A., and J. Overing. 1999. Mass stranding of pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata) in the British Virgin Islands. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 80:759-760.

Rosel, P.E., and H. Watts. 2008. Hurricane impacts on bottlenose dolphins in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Gulf of Mexico Science 25:7.

Smith, C.E., Hurley, B.J., Toms, C.N., Mackey, A.D., Solangi, M., and S.A. Kuczaj II. 2013. Hurricane impacts on the foraging patterns of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus in Mississippi Sound. Marine Ecology Progress Series 487:231-244.

Szesciorka, A.R., Calambokidis, J., and J.T. Harvey. 2016. Testing tag attachments to increase the attachment duration of archival tags on baleen whales. Animal Biotelemetry 4:18.