By Solène Derville, Postdoc, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Science, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

The ocean is vast.

What I mean is that the vastness of the ocean is very hard to mentally visualize. When facing a conservation issue such as increased whale entanglement along the US West Coast (see OPAL project ), a tempting solution may be to suggest « let’s go see where the whales are and report their location to the fishermen?! ». But, it only takes a little calculation to realize how impractical this idea is.

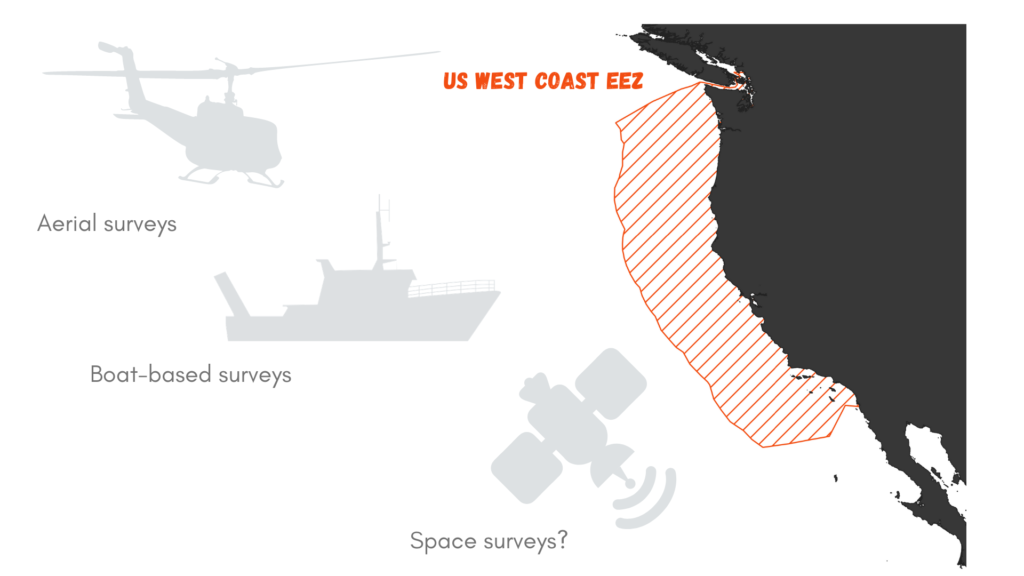

Let’s roll out the numbers. The US West Coast exclusive economic zone (EEZ) stretches from the coast out to 200 nautical miles offshore, as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. It covers an area of 825,549 km² (Figure 1). Now, imagine that you wish to survey this area for marine mammals. Using a vessel such as the R/V Bell M. Shimada that is used for the Northern California Current Ecosystem surveys cruises (NCC cruises, see Dawn and Rachel’s last blog), we may detect whales at a distance of roughly 6 km (based on my preliminary results). This distance of detection depends on the height of the observer, hence the height of the flying bridge where she/he is standing (the observer’s height may also be accounted for, but unless she/he is a professional basket-ball player, I think it can be neglected here). The Shimada is quite a large ship and it’s flying bridge is 13 meters above the water. Two observers may survey the water on each side of the trackline.

Considering that the vessel is moving at 8 knots (~15 km/h), we may expect to be effectively surveying 180 km² per hour (6x2x15). That’s not too bad, right?

Again, perspective is the key. If we divide the West Coast EEZ surface by 180 km² we can estimate that it would take 2,752 hours to survey this entire region. With an average of 12 hours of daylight, this takes us to…

382 DAYS OF SURVEY, searching for marine mammals over the US West Coast. Considering that observations cannot be undertaken on days with bad weather (fog, heavy rain, strong winds…), it might take more than a year and a half to complete the survey! And what would the marine mammals have done in the meantime? Move…

This little math exercise proves that exhaustively searching for the needle in the haystack from a vessel is not the way to go if we are to describe whale distribution and help mitigate the risk of entanglement. And using another platform of observation is not necessarily the solution. The OPAL project has relied on a great collaboration with the United States Coast Guard to survey Oregon waters. The USCG helicopters travel fast compared to a vessel, about 90 knots (167 km/h). As a result, more ground is covered but the speed at which it is traveling prevents the observer from detecting whales that are very far away. Based on the last analysis I ran for the OPAL project, whales are usually detected up to 3 km from the helicopter (only 5 % of sightings exceed that distance). In addition, the helicopter generally only has capacity for one observer at a time.

If we replicate the survey time calculation from above for the USCG helicopter, we realize that even with a fast-moving aerial survey platform it would still take 137 days to cover the West Coast EEZ.

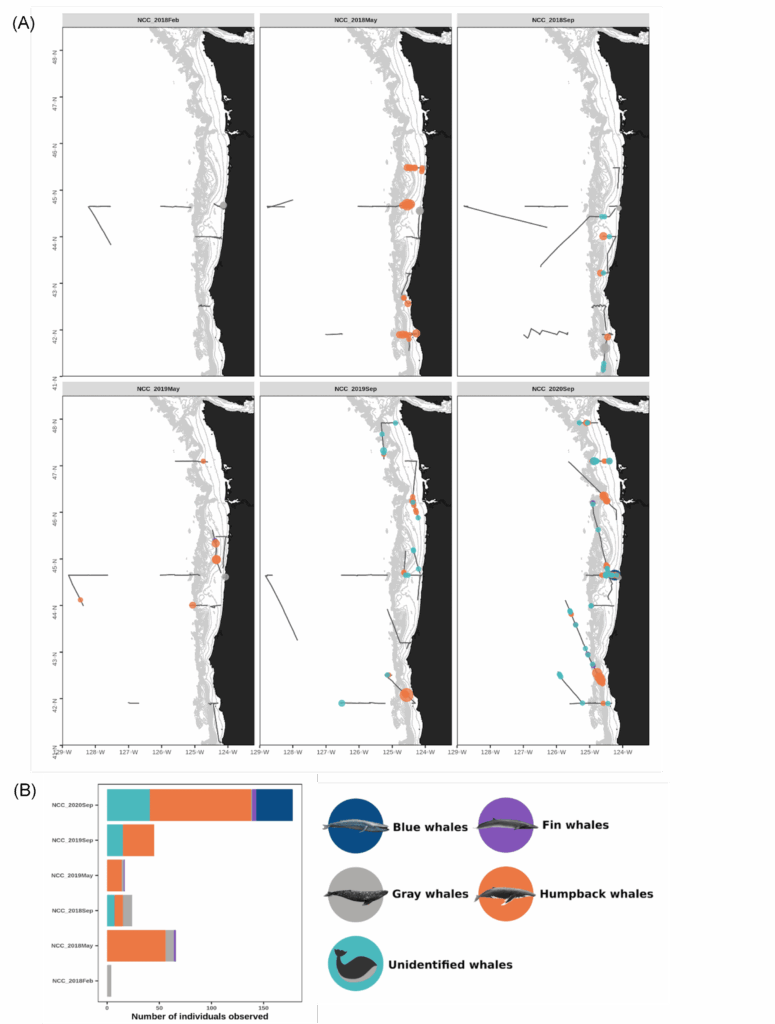

First, we can model and extrapolate. This approach is the path we are taking with the OPAL project: we survey Oregon waters in 4 different areas along the coast each month, then model observed whale densities as a function of topographic and oceanographic variables, and then predict whale probability of presence over the entire region. These predictions are based on the assumption that our survey design effectively sampled the variety of environmental conditions experienced by whales over the study region, which it certainly did considering that all sites are surveyed year-round.

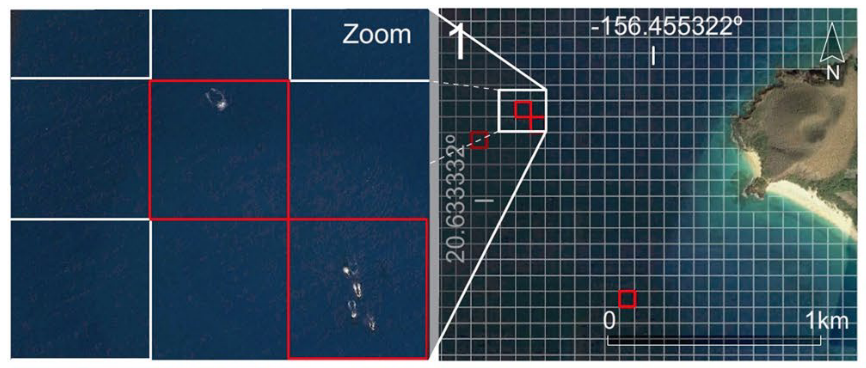

An alternative approach that has been recently discussed in the GEMM Llab, is the use of satellite images to detect whales along the coast. A communication entitled « The Potential of Satellite Imagery for Surveying Whales » was published last month in the Sensors Journal (Höschle et al., 2021) and presents the opportunities offered by this relatively new technology. The WorldView-3 satellite, owned by the company Digitalglobe and launched in 2016, has made it possible to commercialize imagery with a resolution never reached before, of the order of 30 cm per pixel. These very high resolution (VHR) satellite images make it possible to identify several species of large whales (Cubaynes et al. al., 2019) and to estimate their density (Bamford et al., 2020). Furthermore, machine learning algorithms, such as Neural Networks, have proved quite efficient at automatically detecting whales in satellite images (Guirado et al., 2019, Figure 2). While several new ultra-high resolution imaging satellites are expected to be launched in 2021 (by Maxar Technologies and Airbus), this “remote” approach looks like a promising avenue to detect whales over vast regions while drinking a cup of coffee at the office.

But like any other data collection method, satellites have their drawbacks. We recently discovered that these VHR satellites are routinely switched off while passing above the ocean. Specific inquiries would need to be made to acquire data over our study areas, which would be at great expense. One of the cheapest provider I found is the Soar platform, that provides images at 50 cm resolution in partnership with the Chinese Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. They advertise daily images anywhere on earth at $10 USD per km². This might sound cheap at first glance, but circling back to our US West Coast EEZ area calculations, we estimate that surveying this region entirely with satellite imagery would cost more than $8 million USD.

Yet, we have to look forward. The use of satellite imagery is likely to broaden and increase in the coming years, with a possible decrease in cost. Quoting Höschle et al. (2021) ‘To protect our world’s oceans, we need a global effort and we need to create opportunities for that to happen’.

Will satellites soon save whales?

References

Bamford, C. C. G. et al. A comparison of baleen whale density estimates derived from overlapping satellite imagery and a shipborne survey. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12 (2020).

Cubaynes, H. C., Fretwell, P. T., Bamford, C., Gerrish, L. & Jackson, J. A. Whales from space: Four mysticete species described using new VHR satellite imagery. Mar. Mammal Sci. 35, 466–491 (2019).

Guirado, E., Tabik, S., Rivas, M. L., Alcaraz-Segura, D. & Herrera, F. Whale counting in satellite and aerial images with deep learning. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–12 (2019).

Höschle, C., Cubaynes, H. C., Clarke, P. J., Humphries, G. & Borowicz, A. The potential of satellite imagery for surveying whales. Sensors 21, 1–6 (2021).