By Dawn Barlow, PhD student, Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

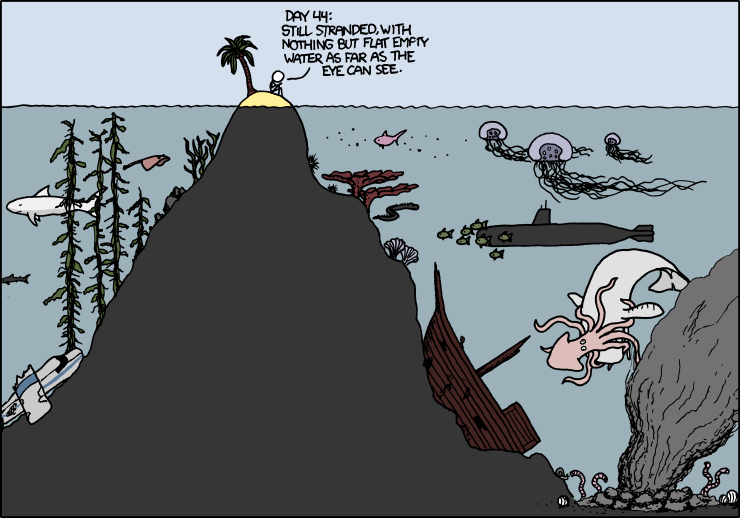

When people hear that I study blue whales, they often ask me questions about what it’s like to be close to the largest animal on the planet, where we do fieldwork, and what data we are interested in collecting. While I love time at sea, my view on a daily basis is rarely like this:

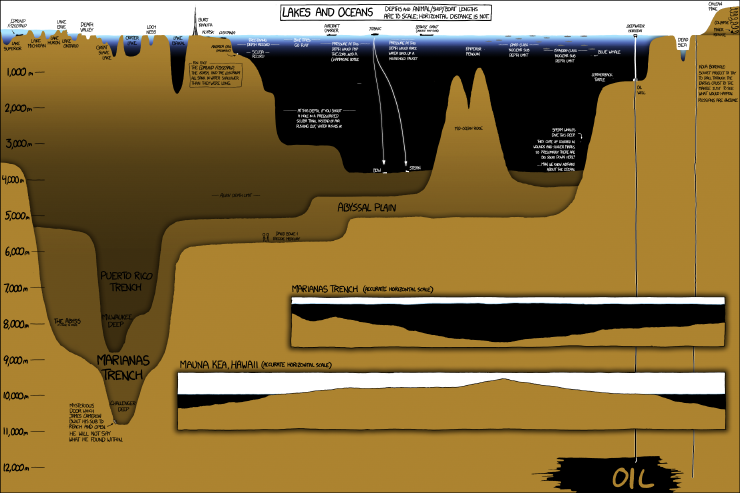

More often than not, it looks something like this:

In my application letter to Dr. Leigh Torres, I wrote something along the lines of “while I relish remote fieldwork, I also find great satisfaction in the analysis process.” This statement is increasingly true for me as I grow more proficient in statistical modeling and computer programming. When excitedly telling my family about how I am trying to model relationships between oceanography, krill, whales, and satellite imagery, I was asked what I meant by “model”. Put simply, a model is a formula or equation that we can use to describe a pattern. I have been told, “all models are wrong, but some models work.” What does this mean? While we may never know exactly every pattern of whale feeding behavior, we can use the data we have to describe some of the important relationships. If our model performance is very good, then we have likely described most of what drives the patterns we see. If model performance is poor, then there is more to the pattern that we have not yet captured in either our data collection or in our analytical methods. Another common saying about models is, “A model is only ever as good as the data you put into it.” While we worked hard during field seasons to collect a myriad of data about what could be influencing blue whale distribution patterns, we inevitably could not capture everything, nor do we know everything that should be measured.

So, how do you go about finding the ‘best’ model? This question is what I’ve been grappling with over the last several weeks. My goal is to describe the patterns in the krill that drive patterns in whale distribution, the patterns in oceanography that drive patterns in the krill, and the patterns in the oceanography that drive patterns in whale distribution. The thing is, we have many metrics to describe oceanographic patterns (surface temperature, mixed layer depth, strength of the thermocline, integral of fluorescence, to name just a few), as well as several metrics to describe the krill (number of aggregations, aggregation density, depth, and thickness). When I multiplied out how many possible combinations of predictor variables and parameters we’re interested in modeling, I realized this meant running nearly 300 models in order to settle on the best ten. This is where programming comes in, I told myself, and caught my breath.

I’ve always loved languages. When I was much younger, I thought I might want to study linguistics. As a graduate student in wildlife science, the language I’ve spent the most time learning, and come to love, is the statistical programming language R. Just like any other language, R has syntax and structure. Like any other language, there are many ways in which to articulate something, to make a particular point or reach a particular end goal. Well-written code is sometimes described as “elegant”, much like a well-articulated piece of writing. While I certainly do not consider myself “fluent” in R, it is a language I love learning. I like to think that the R scripts I write are an attempt to eloquently uncover and describe ecological patterns.

Rather than running 300 models one by one, I wrote an R script to run many models at a time, and then sort the outputs by model performance. I may look at the five best models of 32 options in order to select one. But this is where Leigh reminds me to step back from the programming for a minute and put my ecologist hat back on. Insight on the part of the modeler is needed in order to discern between what are real ecological relationships and what are spurious correlations in the data. It may not be quite as simple as choosing the model with the highest explanatory power when my goal is to make ecological inferences.

So, where does this leave me? Hundreds of models later, I am still not entirely sure which ones are best, although I’ve narrowed it down considerably. My programming proficiency and confidence continue to grow, but that only goes so far in ecology. Knowledge of my study system is equally important. So my workflow lately goes something like this: write code, try to interpret model outputs, consider what I know about the oceanography of my study region, re-write code, re-interpret the revised results, and so on. Hopefully this iterative process is bringing us gradually closer to an understanding of the ecology of blue whales on a foraging ground… stay tuned.