By Dawn Barlow, PhD student, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

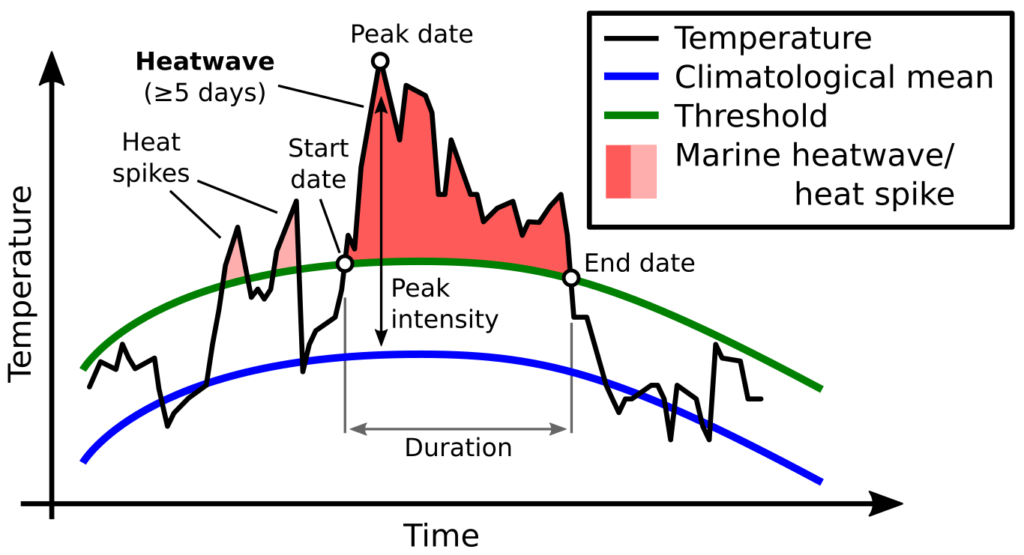

In recent years, anomalously warm ocean temperatures known as “marine heatwaves” have sparked considerable attention and concern around the world. Marine heatwaves (MHW) occur when seawater temperatures rise above a seasonal threshold (greater than the 90th percentile) for five consecutive days or longer (Hobday et al. 2016; Fig. 1). With global ocean temperatures continuing to rise, we are likely to see more frequent and more intense MHW conditions in the future. Indeed, the global prevalence of MHWs is increasing, with a 34% rise in frequency, a 17% increase in duration, and a 54% increase in annual MHW days globally since 1925 (Oliver et al. 2018). With sustained anomalously warm water temperatures come a range of ecological, sociological, and economic consequences. These impacts include changes in water column structure, primary production, species composition, marine life distribution and health, and fisheries management including closures and quota changes (Oliver et al. 2018).

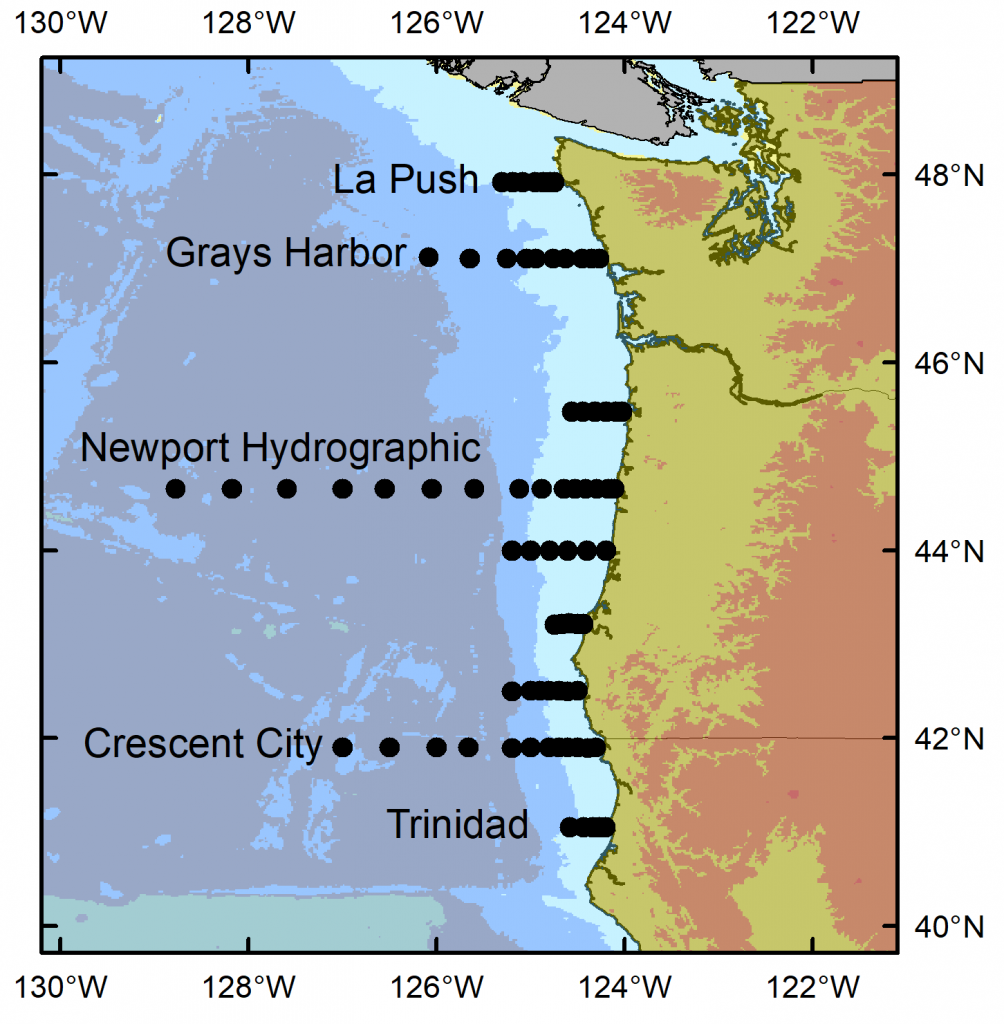

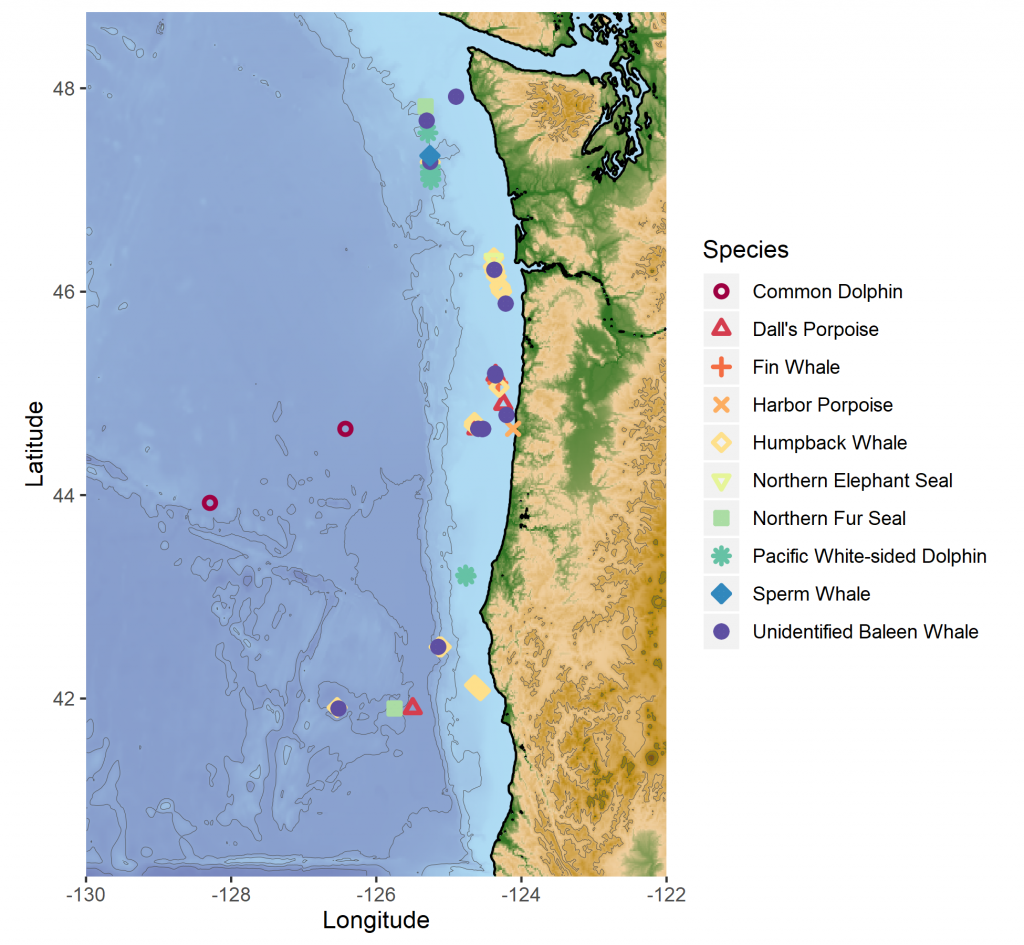

The notorious “warm blob” was an MHW event that plagued the northeast Pacific Ocean from 2014-2016. Some of the most notable consequences of this MHW were extremely high levels of domoic acid, extreme changes in the biodiversity of pelagic species, and an unprecedented delay in the opening of the Dungeness crab fishery, which is an important and lucrative fishery for the West Coast of the United States (Santora et al. 2020). The “warm blob” directly impacted the California Current ecosystem, which is typically a highly productive coastal area driven by seasonal upwelling. Yet, as a consequence of the 2014-2016 MHW, upwelling habitat was compressed and constricted to the coastal boundary, resulting in a contraction in available habitat for humpback whales and a shift in their prey (Santora et al. 2020; Fig. 2).

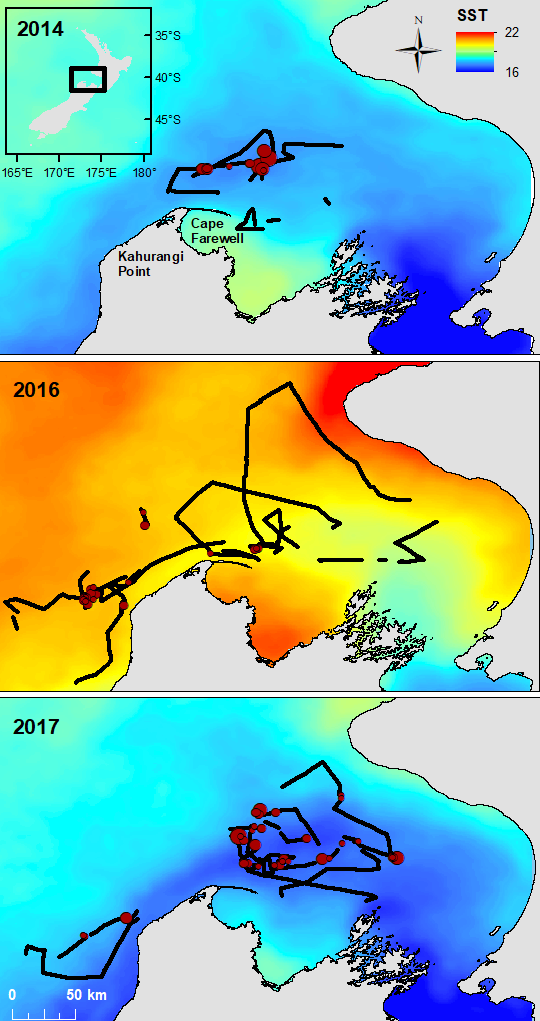

Shifting to an example from another part of the world, the austral summer of 2015-2016 coincided with a strong regional MHW in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, which lasted for 251 days and had a maximum intensity of 2.9°C above the climatological average (Oliver et al. 2017). Subsequently, the conditions were linked to a significant shift in zooplankton species composition and abundance in Australia (Evans et al. 2020). Ocean warming, including MHWs, also appears to decrease primary production in the Tasman Sea and large portions of New Zealand’s marine ecosystem (Chiswell & Sutton 2020). In New Zealand’s South Taranaki Bight region, where we study the ecology of blue whales, we observed a shift in blue whale distribution in the MWH conditions of February 2016 relative to more typical ocean conditions in 2014 and 2017 (Fig. 3). The first chapter of my dissertation includes a detailed analysis of the impacts of the 2016 MHW on New Zealand oceanography, krill, and blue whales, documenting how the warm, stratified water column of 2016 led to consequences across multiple trophic levels, from phytoplankton, to zooplankton, to whales.

The response of marine mammals is tightly linked to shifts in their environment and prey (Silber et al. 2017). With MHWs and changing ocean conditions, there will likely be “winners” and “losers” among marine predators including large whales. Blue whales are highly selective krill specialists (Nickels et al. 2019), whereas other species of whales, such as humpback whales, have evolved flexible feeding tactics that allow them to switch target prey species when needed (Cade et al. 2020). In California, humpback whales have been shown to switch their primary prey from krill to fish during warm years (Fossette et al. 2017, Santora et al. 2020). By contrast, blue whales shift their distribution in response to changing krill availability during warm years (Fossette et al. 2017), however this strategy comes with increased risk and energetic cost associated with searching for prey in new areas. Furthermore, in instances when a prey resource such as krill becomes increasingly scarce for a multi-year period (Santora et al. 2020), krill specialist predators such as blue whales are at a considerable disadvantage. It is also important to acknowledge that although the humpbacks in California may at first seem to have a winning strategy for adaptation by switching their food source, this tactic may come with unforeseen consequences. Their distribution overlapped substantially with Dungeness crab fishing gear during MHW conditions in the warm blob years, resulting in record numbers of entanglements that may have population-level repercussions (Santora et al. 2020).

While this is certainly not the most light-hearted blog topic, I believe it is an important one. As warming ocean temperatures contribute to the increase in frequency, intensity, and duration of extreme conditions such as MHW events, it is paramount that we understand their impacts and take informed management actions to mitigate consequences, such as lethal entanglements as a result of compressed whale habitat. But perhaps more importantly, even as we do our best to manage consequences, it is critical that we as individuals realize the role we have to play in reducing the root cause of warming oceans, by being conscious consumers and being mindful of the impact our actions have on the climate.

References

Cade DE, Carey N, Domenici P, Potvin J, Goldbogen JA (2020) Predator-informed looming stimulus experiments reveal how large filter feeding whales capture highly maneuverable forage fish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

Chiswell SM, Sutton PJH (2020) Relationships between long-term ocean warming, marine heat waves and primary production in the New Zealand region. New Zeal J Mar Freshw Res.

Evans R, Lea MA, Hindell MA, Swadling KM (2020) Significant shifts in coastal zooplankton populations through the 2015/16 Tasman Sea marine heatwave. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci.

Fossette S, Abrahms B, Hazen EL, Bograd SJ, Zilliacus KM, Calambokidis J, Burrows JA, Goldbogen JA, Harvey JT, Marinovic B, Tershy B, Croll DA (2017) Resource partitioning facilitates coexistence in sympatric cetaceans in the California Current. Ecol Evol.

Hobday AJ, Alexander L V., Perkins SE, Smale DA, Straub SC, Oliver ECJ, Benthuysen JA, Burrows MT, Donat MG, Feng M, Holbrook NJ, Moore PJ, Scannell HA, Sen Gupta A, Wernberg T (2016) A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog Oceanogr.

Nickels CF, Sala LM, Ohman MD (2019) The euphausiid prey field for blue whales around a steep bathymetric feature in the southern California current system. Limnol Oceanogr.

Oliver ECJ, Benthuysen JA, Bindoff NL, Hobday AJ, Holbrook NJ, Mundy CN, Perkins-Kirkpatrick SE (2017) The unprecedented 2015/16 Tasman Sea marine heatwave. Nat Commun.

Oliver ECJ, Donat MG, Burrows MT, Moore PJ, Smale DA, Alexander L V., Benthuysen JA, Feng M, Sen Gupta A, Hobday AJ, Holbrook NJ, Perkins-Kirkpatrick SE, Scannell HA, Straub SC, Wernberg T (2018) Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat Commun.

Santora JA, Mantua NJ, Schroeder ID, Field JC, Hazen EL, Bograd SJ, Sydeman WJ, Wells BK, Calambokidis J, Saez L, Lawson D, Forney KA (2020) Habitat compression and ecosystem shifts as potential links between marine heatwave and record whale entanglements. Nat Commun.

Silber GK, Lettrich MD, Thomas PO, Baker JD, Baumgartner M, Becker EA, Boveng P, Dick DM, Fiechter J, Forcada J, Forney KA, Griffis RB, Hare JA, Hobday AJ, Howell D, Laidre KL, Mantua N, Quakenbush L, Santora JA, Stafford KM, Spencer P, Stock C, Sydeman W, Van Houtan K, Waples RS (2017) Projecting marine mammal distribution in a changing climate. Front Mar Sci.