Imogen Lucciano, Graduate student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab.

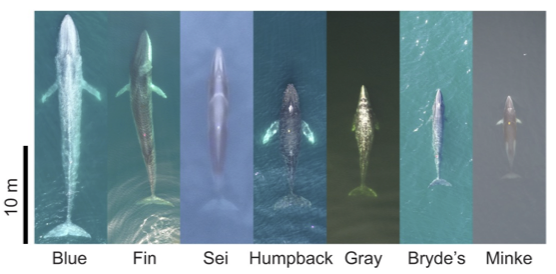

Work in the GEMM lab is booming in all different directions of whale research, and so taking turns writing for the GEMM lab blog gives all of its members an opportunity to highlight topics that are specific and current to us individually. I am two-thirds of the way done with my MSc thesis program, and I’ve recently begun speaking publicly about my work on the HALO project and fin whale acoustic detection off the Oregon coast. In this blog I’ll highlight a two-part question that I am often asked, “Can you see more than fin whales in the data, and how can you tell the species apart when you are looking at it?”. These questions provide great ponderance and are very significant to what I am trying to accomplish. The answer is that I absolutely can see other whales when I am looking through the acoustic data and in fact I have to be quite meticulous in my efforts to tease them apart at times. Let me explain:

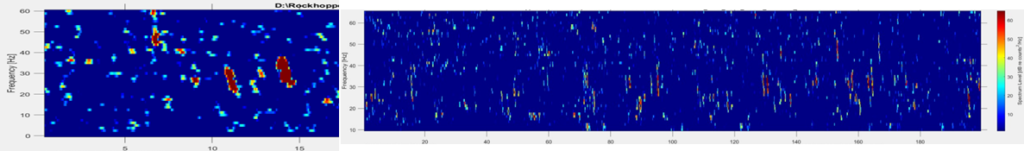

The acoustic data set I am working with tells an important story of the waters off the Oregon coast and will illuminate researchers (and the public) on the presence of all detectable vocal whales and dolphins in the area over the past year, from October 2021 to January of 2023. The advanced technological recording systems, called Rockhoppers, that HALO deploys off the coast of Newport, provide us with continuous sound files for the entire time that they are deployed. (I previously wrote a short blog on Rockhoppers, for those interested in more information.) Then, we analysts (graduate students) on the project work to establish the acoustic presence of our target species within those files.

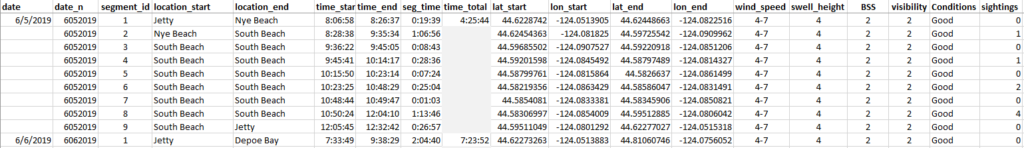

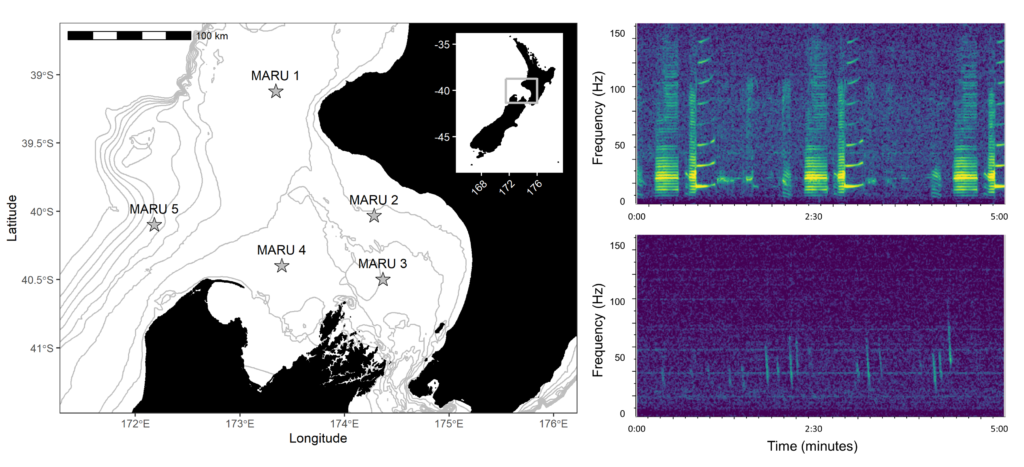

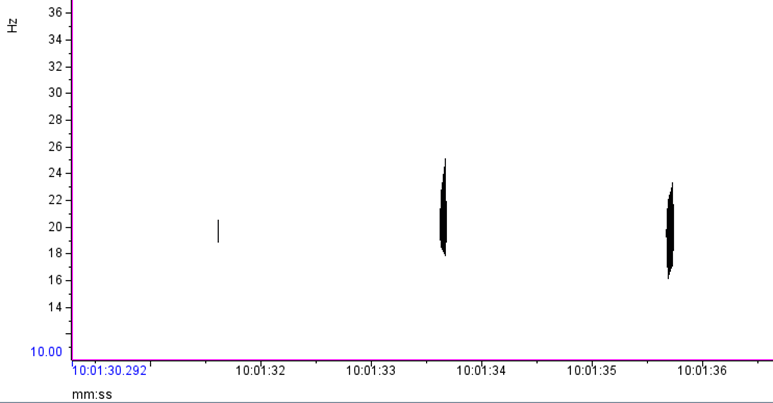

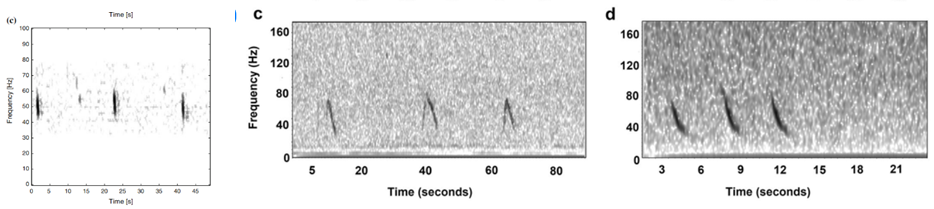

Based on what experts in the field of cetacean bioacoustics currently understand about fin whales, they produce sounds at a very low frequency for both socializing (presumably their 20 Hz pulse call) and for foraging (presumably their 40 Hz downsweep call) (Sirovic et al. 2013; Romagosa et al. 2021). During my efforts to determine the presence of fin whales, it is relatively easy to identify the 20 Hz pulse call, since this call has been well documented in the literature and is the only cetacean call described that occurs in its frequency range. I look for these calls in spectrogram representations of the acoustic data, which allow me to see the selected frequency range over our data collection period (time; Figure 1).

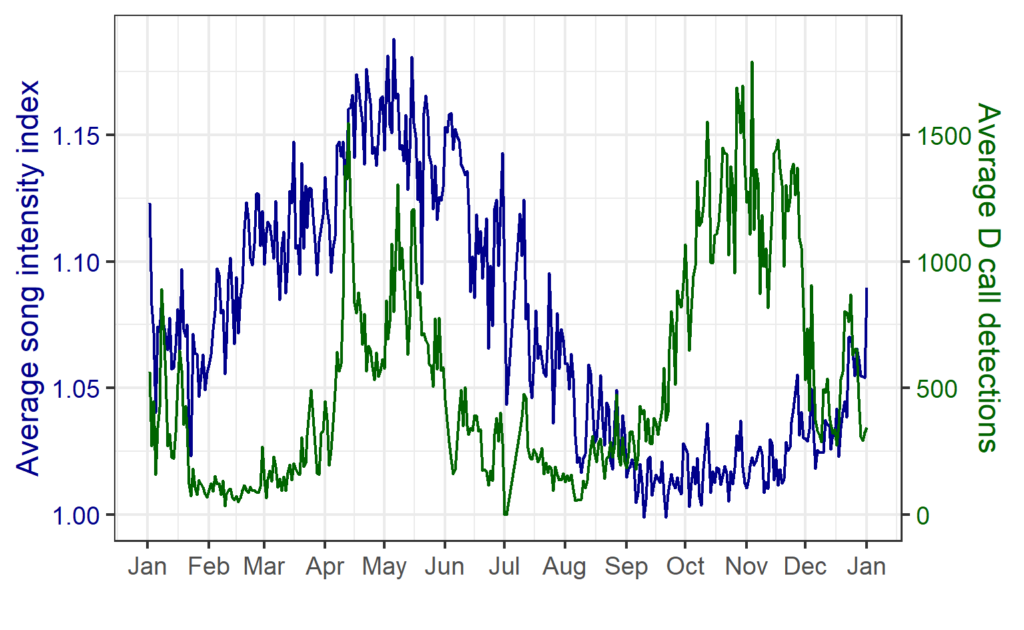

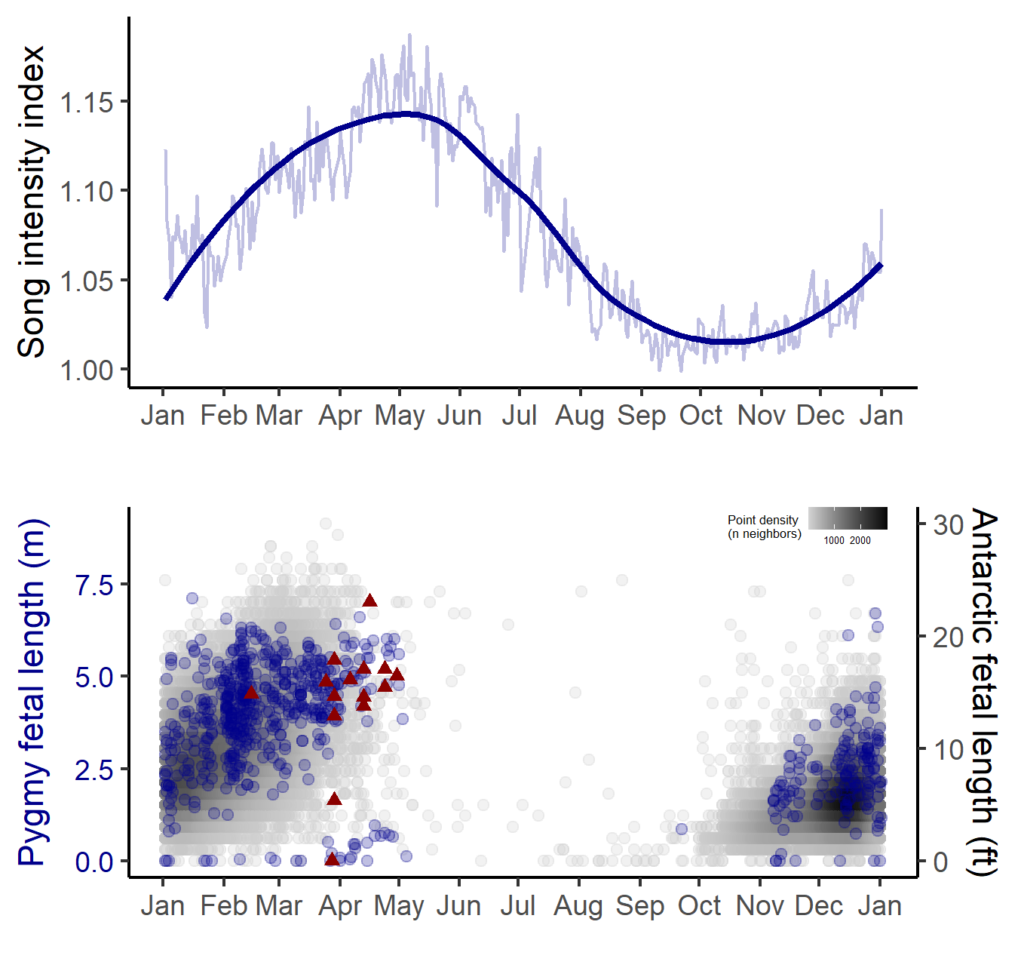

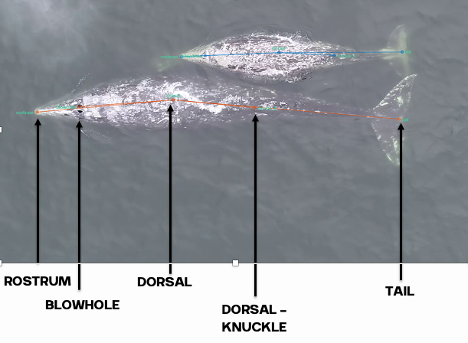

Where this process becomes complicated for me is when I look for the 40 Hz fin whale downsweep call, which is known to occur between ~ 75 Hz – 30 Hz (Wiggins & Hildebrand 2020; Romagosa et al. 2021). This call can vary slightly within this frequency range. Interpretation of this call reaches even higher ambiguity when there are blue whales and sei whales acoustically detected in the same time frame in the same area. The acoustic repertoire of both blue and sei whale calls fall in the same frequency range: blue whales producing what is known as “D calls” and sei whales are known to make low-frequency downsweep calls (Figure 2; Sirovic et al. 2013; Romagosa et al. 2020).

At first glance, the vocalizations from these three whales can be easily confused, and so I am looking for finer details to help tease out the fin whale downsweeps. As shown in Figure 2, there is a difference in the behavior of these calls, with the sei whale call being a shorter call by a matter of 2-3 seconds. The sei whale downsweep calls have not been frequently described in the literature, however those few publications report these calls occurring over 1.4-1.6 seconds (Baumgartner et al. 2008; Espanol-Jimenez et al. 2019) and in each published spectrogram, I have observed this similar boomerang-type looking behavior in the call. Blue whale D calls, on the other hand, are calls produced as social calls while foraging (Szesciorka et al 2020) and known to occur over ~1.8 seconds (Oleson et al. 2007).

Fin whale 40 Hz calls have a duration of about one second and are not known to be produced in a regular sequence (Sirovic et al. 2013), thus I am teasing them out carefully from what can sometimes appear like a diversly grouped choir of low frequency whale song among the HALO data (Figures 3 & 4).

Although there are some known seasonal patterns of each of these aforementioned whale calls (Sirovic et al. 2013; Szesciorka et al. 2020), many data gaps remain of the temporal patterns of the 40 Hz and 20 Hz calls (i.e., when the calls occur) off the Oregon coast. Therefore, I cannot assume that I will only see 40 Hz calls in any time period. I need to assess the behavior of the calls I detect and tease out the calls I know surely are fin whale 40 Hz downsweeps in each file of the entire acoustic dataset.

Afterthought: The HALO project is new and has only just collected its first year of acoustic data, however the project is intent to continue deploying and collecting Rockhoppers off the Oregon coast for years to come. As this acoustic data set continues to grow it will be used by other researchers, and I (among the first to process and analyze it) feel some pressure to get things done right. As I process these data I will work hard to make the best-informed call identifying fin whales in the 40 Hz range. This focus and feeling of responsibility reassure me that I am in the appropriate career field. I really care about how these data are processed, where the research will go from here, and how it influences human activities in this critical whale habitat.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.

References

Baumgartner, M., Van Parijs, S., Wenzel, F., et al. 2008. Low frequency vocalizations attributed to sei whales. Acoustical Society of America, 124 (2): 1339-1349. https://www.whoi.edu/cms/files/JAS001339_59390.pdf.

Espanol-Jimenez, S., Bahamonde, P., Chiang, G., Haussermann, V. 2019. Discovering sounds in

Oleson, E., Calambokidis, J., Burgess, W,. et al. 2007. Behavioral context of call production by eastern North Pacific blue whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 330 : 269-284. https://www.int-res.com/articles/meps_oa/m330p269.pdf.

Romagosa, M., Baumgartner, M., Cascao, I., et al. 2020. Baleen whale acoustic presence and behavior at a Mid-Atlantic migratory habitat, the Azores Archipelago. Scientific Reports, 10. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339952595_Baleen_whale_acoustic_presence_and_behaviour_at_a_Mid-Atlantic_migratory_habitat_the_Azores_Archipelago.

Romagosa, M., Perez-Jorge, S., Cascao, I., et al. 2021. Food talk: 40-Hz fin whale calls are associate with prey biomass. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288 (1954): 20211156. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34229495/.

Sirovic, A., Williams, L., Kerosky, S., Wiggins, S., Hildebrand, J. 2013. Temporal separation of two fin whale call types across the eastern North Pacific. Marine Biology, 160: 47-57.

Szesciorka, A., Ballance, L., Sirovic, A., et al. 2020. Timing is everything: drivers of interannual variability in blue whale migration. Scientific Reports, 10 (7710). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-64855-y. Wiggins, S. & Hildebrand, J. 2020. Fin whale 40 Hz behavior studied with an acoustic tracking array. Marine Mammal Science, 36 (3). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339575220_Fin_whale_40-Hz_calling_behavior_studied_with_an_acoustic_tracking_array.