By Solène Derville, Postdoc, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Science, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

This blog is motivated by the recent publication I co-authored with my former PhD supervisor in New Caledonia (Garrigue & Derville 2022). As I am about to present our study entitled “Behavioral responses of humpback whales to biopsy sampling on a breeding ground: the influence of age-class, reproductive status, social context, and repeated sampling” as part of the Society for Marine Mammalogy Seminar Editor’s Selected Series, I have been reflecting on how my research impacts the animals I study.

The overwhelming majority of marine mammal scientists around the world agree that lethal sampling of whales and other marine mammals is unnecessary to fill current knowledge gaps and deplorable in a context of global biodiversity loss and habitat degradation (e.g., Clapham et al. 2003; Cote and Favaro 2016). More so, the academic community consistently seeks to improve the ethical framework within which research on live animals is conducted. While the study of free-living marine mammals poses challenges that are quite different than laboratory experiments, these practices are nonetheless discussed and questioned by the general public, managers, and the scientists themselves.

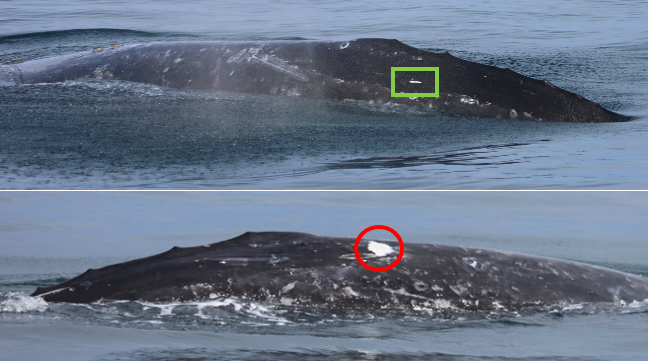

Among the field methods used to collect data from cetaceans, biopsy sampling is perhaps one of the most common. While it is sometimes possible to skim the water to collect the dead skin that individuals may shed during surface activities, cetaceans are most often biopsied remotely, using a veterinary rifle or a crossbow (Figure 1). The devices propel an arrow or a dart towards the animals to remove a small piece of skin and blubber inside a tip. These pieces can be a few centimeters to less than a centimeter long depending on the size of the species that is targeted (e.g., smaller darts are typically used for dolphins compared to large whales). The tissues sampled in this way are essential to address many biological, ecological, and behavioral questions that can ultimately inform conservation. Yet, biopsy sampling is invasive and a few studies have investigated its potential impact on humpback whales (Cantor et al., 2010; Clapham & Mattila, 1993), among other cetaceans (see review in Noren & Mocklin, 2012).

When presenting biopsy sampling to the general public, who hasn’t had to answer the tricky question “but does it hurt?”? Well I wish the whale could pop its head out the water and just tell me if it did! Measuring disturbance or pain is unfortunately extremely challenging in the case of cetaceans. Sophisticated methods that rely on new technologies (hormone analysis, drone video footages etc.) are being developed by the GEMM lab and other research groups to assess the impact of human activities around whales and should allow a better understanding of acute and chronic stress in the near future.

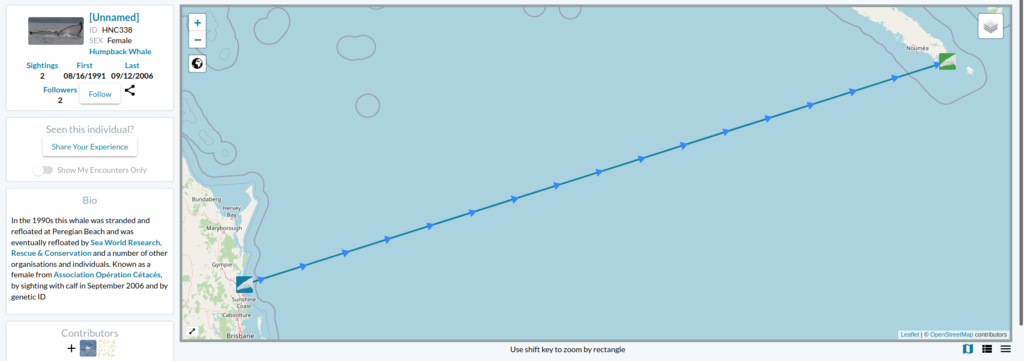

The strength of our study that was just published in the Marine Mammal Science journal is not technology, but rather the application of very standard approach over many years of consistent field work. In New Caledonia, in the southwest Pacific, humpback whales have been monitored as part of a long-term program initiated in the mid ‘90s by Dr. Claire Garrigue. Every austral winter, when whales regroup in these warm subtropical waters to breed and nurse their calves, biopsy samples were collected on individuals of all age-classes: adults, juveniles, and calves. During each of the 2,249 biopsies conducted throughout 20 years of research, the behavioral response of individual whales was qualitatively assessed and recorded. First, the response to the boat approach was recorded (whether the whale avoided the boat or not), then the response to the biopsy immediately after the shot, which was categorized as none, weak, moderate, or strong, based on general definitions provided by Weinrich et al. 1991. We investigated the frequency of these behavioral responses according to age-class, sex, female reproductive status, and social context, as well as the sampling system and habitat. We also assessed the effect of repeated biopsy sampling over time at the individual level.

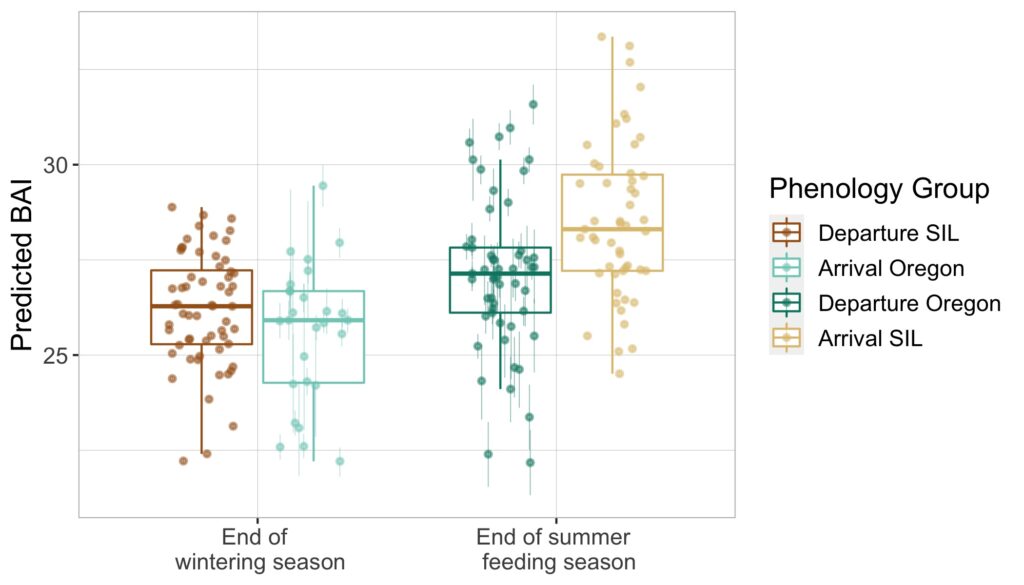

We found that humpback whales did not show observable behavioral responses in over half of the cases (58.7%). Interestingly, we also discovered that calves did not respond more than adult whales, whereas juveniles stood out as the most sensitive age-class (Figure 2). Mothers with a calf reacted more often to the boat compared to non-lactating females and males, but paradoxically had the weakest responses to the biopsy sampling itself. We interpreted this dual response as the result of individually varying baseline stress levels, with some very shy mothers actively avoiding boats and others displaying a very oblivious attitude to both the boat’s proximity and to the brief impact of the biopsy sampling.

Although biopsies could have stressed animals in a way that was not measurable with our simple behavioral approach, it is still reassuring to see that most whales did not show a response, which allows us to assume that the impact of the biopsy was very minimal. This sort of methodological research is needed to inform managers responsible for the delivery of research permits and for researchers themselves to keep questioning their practices.

As I was analyzing this data and writing the paper, I became more aware of the value each of these tissue samples had. In the case of biopsy sampling, I believe that the gain in knowledge is ultimately worth the cost, but we should always bear in mind that this conclusion comes from a human perspective. From when I am in the field approaching whales, to when I analyze the hard-won data in my office, I think about the ethics of our work. As a supporter of open science, my take-away message from this research journey was that we have responsibility to use and share this biological data as much as possible. We should always aim at making the most out of data, but even more so when it is acquired by working with live animals. The cost is never null, so let’s make it worth it!

Ethics statement

Research was conducted under annual permits delivered by the competent authorities of the government of New Caledonia, and the Northern Province and Southern Province of New Caledonia. This study was carried out following the marine mammal treatment guidelines of the Society for Marine Mammalogy. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available here (DataSuds repository, doi: 10.23708/QYWDPO).

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.

References

Cantor, M., Cachuba, T., Fernandes, L., & Engel, M. H. (2010). Behavioural reactions of wintering humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) to biopsy sampling in the western South Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 90(8), 1701–1711. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315409991561

Clapham, P. J., & Mattila, D. K. (1993). Reactions of humpback whales to skin biopsy sampling on a West Indies breeding ground. Marine Mammal Science, 9(4), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1993.tb00471.x

Cote, Isabelle M., and Corinna Favaro. “The scientific value of scientific whaling.” Marine Policy 74 (2016): 88-90.

Garrigue, C., & Derville, S. (2022). Behavioral responses of humpback whales to biopsy sampling on a breeding ground : the influence of age-class , reproductive status , social context , and repeated sampling. Marine Mammal Science, 38, 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12848

Noren, D. P., & Mocklin, J. A. (2012). Review of cetacean biopsy techniques: Factors contributing to successful sample collection and physiological and behavioral impacts. Marine Mammal Science, 28(1), 154–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1748-7692.2011.00469.x

Phillip J. Clapham, Per Berggren, Simon Childerhouse, Nancy A. Friday, Toshio Kasuya, Laurence Kell, Karl-Hermann Kock, Silvia Manzanilla-Naim, Giuseppe Notabartolo Di Sciara, William F. Perrin, Andrew J. Read, Randall R. Reeves, Emer Rogan, Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, Tim D. Smith, Michael Stachowitsch, Barbara L. Taylor, Deborah Thiele, Paul R. Wade, Robert L. Brownell, Whaling as Science, BioScience, Volume 53, Issue 3, March 2003, Pages 210–212, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0210:WAS]2.0.CO;2

Weinrich, M. T., Lambertsen, R. H., Baker, C. S., Schilling, M. R., & Belt, C. R. (1991). Behavioural responses of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the southern gulf of Maine to biopsy sampling. Reports of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 13,91–97