According to the staff at Oak Creek and many other gardeners and farmers I’ve had the opportunity to talk to, it appears that though 2020 was a difficult year for humans, it was truly a remarkable year for gophers and other rodents.

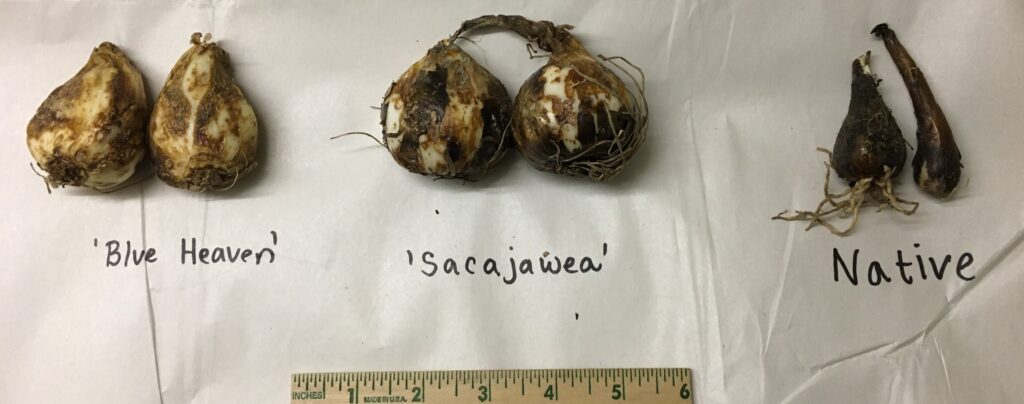

From left to right: wild type Great Camas, Camassia leichtlinii, the native cultivar ‘Sacajawea’, and the native cultivar ‘Caerulea Blue Heaven’.

Gophers & Camas

No matter how often a gopher was trapped and removed from Oak Creek last summer, the next week there would always be a mound of freshly turned soil on the grounds, indicating a new gopher had taken its place. While they seemed to enjoy popping up in some of the Organic Gardening Club’s beds, they had an extra fondness for my own experimental garden beds. Fresh gopher-turned soil was most commonly found in any plot growing our native Camassia leichtlinii (Great Camas) and the plots surrounding them.

We planted our 15 camas plots in the fall of 2019. Five plots were planted with the wild type camas species, Camassia leichtlinii (Great Camas). Five more were planted with the C. leichtlinii cultivar ‘Caerulea Blue Heaven’, and the final five were planted with C. leichtlinii ‘Sacajawea’. By the spring of 2020, the camas plots were relatively untouched, aside from some minor grazing by deer on a handful of plots. In April our three camas varieties began blooming in sequence (the native first, followed by ‘Blue Heaven’ and ‘Sacajawea’, respectively), and by mid June they had all gone to seed.

Though the gopher troubles seemed to really begin in June, there were signs of their activity that we did not heed. In spring of 2020 I was planting a Clarkia amoena cultivar plug. Upon removing some soil to make room for the plant, I found that the soil seemed to drop off into a massive hole beneath the plot I was planting. I shook some soil loose to fill the hole, planted my Clarkia, and moved on. Later in the season, a different Clarkia plant would be found dead, and upon its removal, another tunnel would be found beneath the top layer of soil.

By August, there had been so much gopher activity in our beds that I decided we needed to conduct a damage assessment. I asked Tyler to dig around in a Camas plot that seemed particularly ravaged by the gophers, to see if he could find any of the original 40 bulbs we had planted. His searching returned no bulbs.

Bulb Thieves

I immediately went through each of the 15 camas plots and rated them with a visual assessment of the gopher activity that we would use to determine how many bulbs likely remained in the plots. The levels we decided on were “low/no damage” “Low damage”, “Moderate Damage”, “High Damage” and “Extreme Damage”. Plots with no damage were expected to have all 40 original planted bulbs. On the other end of the spectrum, plots labeled “Extreme” were expected to have no remaining bulbs.

At the end of our field season, we dug out the bulbs from each of the camas plots so we could assess the actual damage, and so we could install fencing to keep all future gophers out. During the bulb dig, we recorded the total number of bulbs found in each plot. In the table below, I have shared the visual damage rating for each plot, the estimated number of bulbs expected to be in the plots, and the actual number of bulbs we found.

| Rep # | Bulb Type | Visual Damage Rating | Estimated Remaining Bulbs | Actual Remaining Bulbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blue Heaven | Low-no | 40 | 2 |

| 2 | Blue Heaven | Low-no | 40 | 66 |

| 3 | Blue Heaven | High | 10 | 53 |

| 4 | Blue Heaven | High | 10 | 66 |

| 5 | Blue Heaven | High | 10 | 5 |

| Totals | 110 | 192 | ||

| 1 | Native | Extreme | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Native | Low | 40 | 8 |

| 3 | Native | Extreme | 0 | 8 |

| 4 | Native | Extreme | 0 | 30 |

| 5 | Native | High | 10 | 3 |

| Totals | 50 | 49 | ||

| 1 | Sacajawea | High | 10 | 0 |

| 2 | Sacajawea | High | 10 | 0 |

| 3 | Sacajawea | Moderate | 20 | 0 |

| 4 | Sacajawea | Low-no | 40 | 0 |

| 5 | Sacajawea | Moderate | 20 | 0 |

| Totals | 100 | 0 |

While our findings from this unexpected study of bulbs were unfortunate, they tell an interesting story. An important point to note is that many of the bulbs have divided since they were planted, which is why in a few cases we found more than the original 40 planted bulbs. Regardless, there is a clear preference for the native C. leichtlinii and native cultivar ‘Sacajawea’ bulbs over the ‘Blue Heaven’ cultivar. We also noticed that any bulbs that were planted more shallow than the recommended 2-3x the height of the bulb were missed by the gophers.

Finding the Gopher Stash

After the exploratory bulb digging, we excavated each of our camas plots to around 1 foot in depth to install fences to keep the gophers from returning to our plots. While digging out the excess soil, we would often find a bulb or two that weren’t located during the initial bulb removal (these numbers are not included in Table 1, as we did not record them). In one section where the three camas types were planted in a row, we excavated a huge section of the garden, and made an amazing discovery (extra Kudos to Tyler who did the bulk of the work on this section).

On one of the walls of the hole, we found a gopher food chamber with thick white roots sticking out of the bottom of it. We removed some soil from the entrance, and discovered a chamber filled with camas bulbs. We carefully removed them and found over 60 bulbs that had been stolen from our plots.

The 3 excavated plots, the food chamber, and the pile of 66 bulbs removed from the burrow.

Some of the bulbs were clearly the wild type great camas, identified by their characteristic long neck. The others we suspect to be ‘Sacajawea’ bulbs, as the burrow was found in what used to be a ‘Sacajawea’ plot. Any unknown bulbs were brought to my home and planted in a planter box to be identified in the next couple of months. The ‘Sacajawea’ bulbs have variegated foliage, making them easy to pick out once their shoots appear above the soil. We won’t know if the remaining mystery bulbs are ‘Blue Heaven’ or large wild type bulbs until they bloom in the spring.

Moving Forward

On the left: Jen (me) building a gopher exclosure. On the right: Tyler finishing installing a gopher exclosure.

In November of 2020 we installed our fences, refilled the gaping holes with soil, and replanted all of the camas bulbs, including some supplemental purchased bulbs of each of the three varieties. The native Camas and ‘Blue Heaven’ were successfully replanted with 40 bulbs. We were only able to order enough ‘Sacajawea’ bulbs to achieve a density of 30 bulbs per plot, though they will receive additional geophytes if any of the mystery bulbs turn out to be variegated. The mystery bulbs have yet to push their shoots through the soil, but I will include an update on their identities when I have them.

Thank you to Tyler, Izzy, Max, and my fiancé Elliot for helping out in this laborious process. I absolutely would not have been able to safeguard the new camas plantings without your efforts and support in this process.