Once a month the Roadrunner Foodbank distributes pounds and pounds of food on the Mescalero Apache reservation in southern New Mexico. I lived and worked in Mescalero for a little over a year as an Americorps volunteer on an educational farm in 2015. I often helped distribute food to the many families that came to collect items, and I even received some food myself. The food bank provides an excellent service to a great number of families and individuals on the reservation, however, there were some less than desirable facets. We would often receive highly processed and sugar-laden foods, like cookies and cakes, and sometimes we would receive produce like chayote squash and aloe leaves that local people didn’t know how to cook. One month we received an inordinate amount of chewing gum. Bread, produce, and other canned goods were incredibly useful and well received by the Apache families, but some items weren’t exactly nutritional or beneficial.

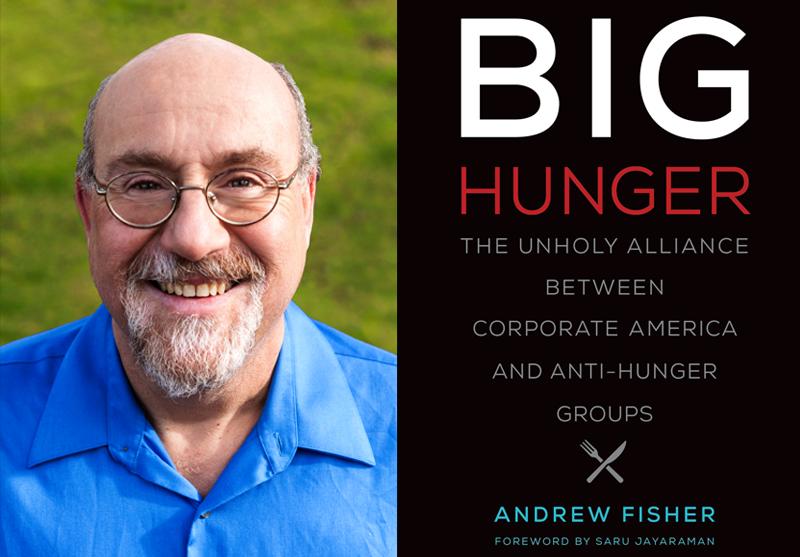

Currently, within the United States, there are approximately 200 food banks that distribute food to over 60,000 food pantries (Fisher 2017). As of 2016, 46 million Americans visited food pantries, approximately 1 out of every 7 people. Although the generous charity and rosy intentions of kindly Americans certainly aid many of the hungry and poverty-stricken individuals in the U.S, most donors fail to recognize the underlying alliance between anti-hunger campaigns and big business. In his latest book, “Big Hunger”, Andrew Fisher untangles the insidious webs woven between corporate interest and charitable agencies. I attended Mr. Fisher’s short, but enlightening talk on the topics discussed in his book at Grassroots bookstore in late October.

Andrew Fisher began his talk by addressing the history of these charitable organizations in this country. Food banks gained popularity in the United States in the early 1980’s due to the economic recession coupled with president Reagan’s slashing of economic safety nets (Fisher 2017). Since then, food banks have become a commonplace and accessible service across the United States. However, the growth of food banks has been seen to benefit some far more than others. According to Andrew Fisher, some CEOs of food banks rake in upwards of $250,000 annually. The roots of big business have also snaked their way into the workings of food banks, with 22% of food bank board members being affiliated with fortune 1000 companies like Kraft and Walmart. These companies hold a certain level of clout when it comes to making policy for food bank operations. For example, food banks typically measure success by the weight of food received and donated. This sounds like a plausible technique until one considers that liters of soda weigh far more than bread or romaine lettuce. The lettuce lobby appears vastly underfunded compared to PepsiCo.

Walmart, the largest corporation in the United States, is renowned for their millions of pounds of donations to charities and food banks across the country (Forbes 2017). However, Andrew Fisher contends, that this is a huge ploy to gain popularity among consumers (Fisher 2017). He attests that although Walmart certainly isn’t anti-hunger they are not anti-poverty. One could argue that they actually thrive on poverty. In fact, it is commonplace for Walmart to encourage their employees to visit food banks and sign up for government benefits, such as SNAP, that can be spent at their stores. According to an article published by Forbes, in the year 2013 Walmart accounted for 18% of sales involving SNAP benefits (Forbes 2014). The article cites a report conducted by the Americans for Tax Fairness coalition that calculated U.S. taxpayers paid $6.2 billion in public assistance to low wage Walmart employees in 2013. Fisher asserts that Walmart store employees that do not hold managerial positions often work a 32 hour work week so that Walmart can legally avoid denying them the benefits that go along with full-time employment (Fisher 2017).

What if Walmart did decide to pay a higher hourly rate? Would prices soar? Not really. The Labor Center at UC Berkeley determined that if Walmart paid all of their employees at least $12 per hour it would cost them $3.2 billion, 1% of the companies annual sales (Jacobs 2011). If Walmart decided to pass off the cost of raised wages to the consumer, the study finds that it would cost the average shopper about $12.50 more per year. For workers earning less than $9 per hour, this $12 per hour wage increase would amount to an extra $3,250- $6,500 in their pockets annually. That would mean less need for public assistance, and less reliance on food pantries for meeting basic needs. The solution to poverty lies in addressing not just hunger, but also wages.

As the season of giving fast approaches, many Americans will be donating to the plentiful food drives and food banks across the nation. Although the relationship between anti-hunger campaigns and big business is quite shady indeed, there are 41.2 million people in the United States that are food insecure (USDA 2017). Donating to a food bank or pantry is very generous and kindhearted, and by no means should anyone discontinue supporting hungry individuals and families. However, if we as a country wish to truly assist those in need we must help pull people out of poverty instead of continuing this cycle of impossibly low wages coupled with the constant need for assistance. If we really wish to help those in need perhaps we should couple our fight against hunger with a fight for fifteen.

FISHER, A. (2017). BIG HUNGER: the unholy alliance between corporate america and anti-hunger groups. S.l.: MIT PRESS.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2014/04/15/report-walmart-workers-cost-taxpayers-6-2-billion-in-public-assistance/#69023ebb720b

Jacobs, K. Could Walmart Pay a Living Wage? (2011) http://www.californiaprogressreport.com/site/could-walmart-pay-living-wage

USDA Key Statistics & Graphics. (2017, October 4). https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx