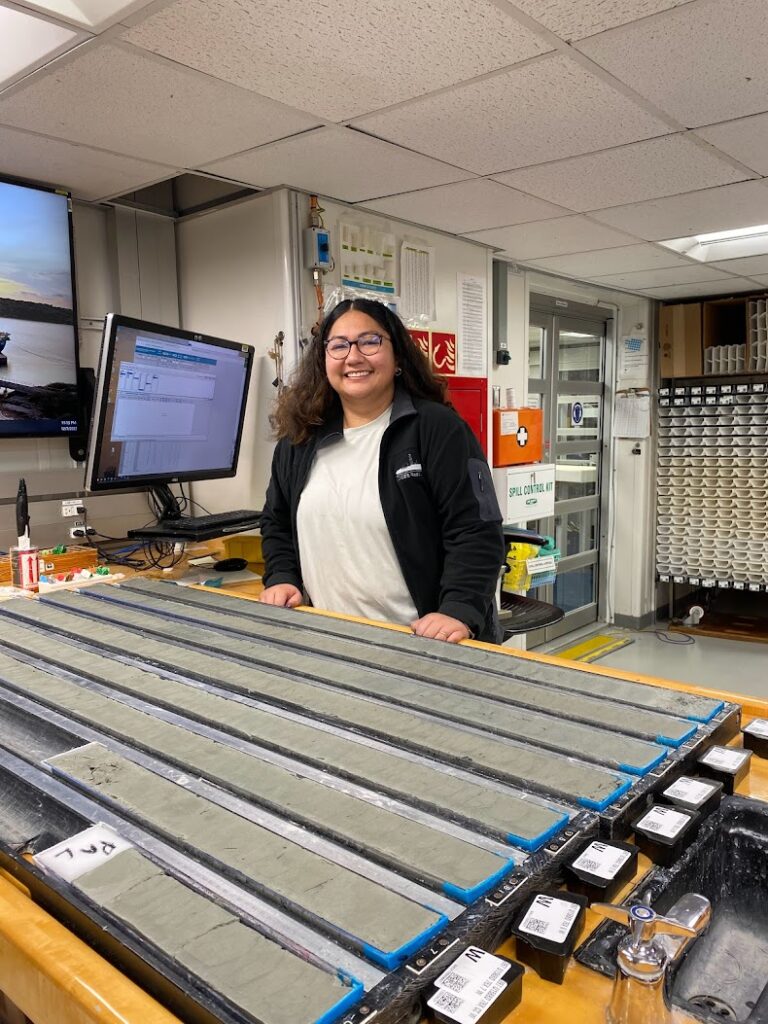

Julia Marks Peterson, 4th year OEAS PhD student (MG&G)

I sent in my United States Antarctic Program deployment packet this week, and suddenly returning to the field for another season feels right around the corner. Memories from last year sporadically surfaced as I answered the prompts asked in the packet.

“What dates will you need a hotel in Christchurch, NZ?” I filled out the same hopeful answer as before: The first two days of November, while reminiscing about the two weeks we were unexpectedly stuck there as McMurdo Station tried to reign in a COVID outbreak. “What size parka would you like?” brought me back to seeing my Big Red for the first time, with my name on the pocket and the reality sinking in that we were going to a very, very cold place.

I am heading back to Antarctica as a member of the COLDEX project. COLDEX (the Center for OLDest ice EXploration) is a National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center with the driving research goal of finding the oldest ice in Antarctica. Currently, this quest is a two-pronged effort, being carried out by an exploration team and an ice core drilling team. The exploration team is composed of geophysicists who will fly over a section of the ice sheet in a plane outfitted with airborne radar to collect high-resolution imagery of the ice sheet interior. The goal is to use these images to select a site to drill a deep ice core that extends back 1.5 million years.

Simultaneously, the ice core drilling team will continue to drill shallow cores from a place called the Allan Hills Blue Ice Area, where the oldest ice ever dated has been collected. The Allan Hills are in East Antarctica, just on the other side of the Transantarctic Mountains from McMurdo Station. Unlike the parts of an ice sheet where winter snowfall is preserved (like high points such as domes), the Allan Hills Blue Ice Area loses surface mass over the year due to high winds and sublimation, the process whereby ice turns directly to gas without passing through a liquid water state. This net loss is balanced by ice flow from an accumulation area upstream, causing uplift of ice that was formerly in the ice sheet interior. Scientists have had a hunch that the ice in this area was old for a long time because meteorites collected nearby were determined to have terrestrial ages of up to ~400,000 years. And they were right! For the past decade, research teams have drilled ice cores at the Allan Hills BIA and progressively extended the ice core record further back in time. Though the flow and uplift of old ice causes the layers in the ice to be distorted, leading to a discontinuous record, ice as old as 4 million years has been found.

As a member of the ice drilling team, I will return to the Allan Hills BIA where we hope to collect even older ice. Like last year, we will fly to Christchurch, New Zealand where the U.S. Antarctic Program transports people to and from the largest base on the continent: McMurdo Station. Once at McMurdo, we will go through required trainings, including how to safely live away from station in the “deep field.” After about 10 days, we will be flown to the Allan Hills in a small aircraft that flies so low that you feel like you’re weaving through the mountains. We will then set up camp and live at the Allan Hills, drilling ice for eight weeks before returning to McMurdo and then back home via Christchurch.

Antarctic fieldwork is a funny thing; every memory is an initial flood of positive emotions followed by a slightly uncomfortable aftertaste. It’s easy to remember all the fun camp games, the ridiculous jokes upon jokes, the stunning landscape, the products of our hard work, and the beautiful friendships built. However, married to all these memories are the strenuous parts of life in the field. How gross your hair can get after weeks of living in a desert without a shower. How a task you could accomplish in one minute in your normal life would take you 20 (e.g., if you suddenly realize you really have to pee it’s already too late). How cold it would feel to open your sleeping bag in the morning and put on clothes that have equilibrated with Antarctic temperatures. How it would feel when the propane tank fueling the heater depleted and your only path back to warmth was the long and onerous task of replacing the tank. Oh, and the constant wind! So much wind.

As I write this, remembering the negative parts of Antarctica while sitting in peak Corvallis summer temperatures, it becomes hard to imagine returning to that way of life. But these memories are never the first that come to mind. It actually takes work to remind myself of these tough details because the fond parts so easily eclipse them. I think that is what might be most remarkable about Antarctic fieldwork, that it is this incredible showcasing of how adaptable we can be. And it’s this realization that makes me so excited to return for another season.